The untold story of Britain's first black school teacher

- Published

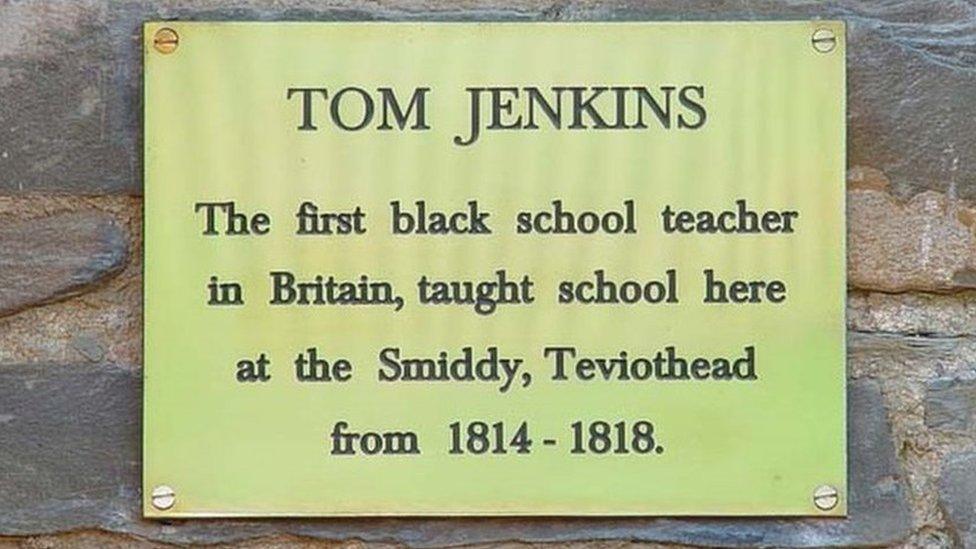

A small plaque commemorates the role Tom Jenkins played in education in the Borders

A small plaque marks the spot where the man believed to be Britain's first black school teacher educated children in a Scottish village.

Now the story of Tom Jenkins' life is being explored as part of the area's Alchemy Festival,, external and there are calls for him to receive greater recognition.

Jenkins educated dozens of children between 1814 and 1818 at Teviothead, near Hawick, in the Scottish Borders.

Artist Dr Jade Montserrat has been investigating the links between Hawick and both Jenkins and anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass, who visited the town in 1846.

"I focused in on the significant black presence in Hawick and, more loosely, Hawick's liberal abolitionist identity as a town," she said.

"It became clear that this was a sort of unrecognised, significant history."

Dr Jade Montserrat has researched the Jenkins story during a six-month residency with the Alchemy Festival

She hopes to ensure wider knowledge of their "significant contribution" to the area.

Dr Jade Montserrat said Jenkins was thought to be Britain's first black school teacher.

He was born in 1797 somewhere on the Upper Guinea coast, in modern day Guinea, Sierra Leone or Liberia.

When he was six years old his father, a slave trading chief, handed him to Capt James Swanson.

The son of a waiter from Hawick, Capt Swanson was in command of the slave ship Prudence.

The intention was that Tom Jenkins would be educated in Britain before returning to West Africa.

"The Prudence set sail for Liverpool - at that time Britain's main slaving port - with young Tom on board," said Dr Monserrat.

"From there, Tom Jenkins went with his guardian, James Swanson, to Hawick - a town then in the early years of its industrialisation."

However, Swanson died a few days after their return and Jenkins was taken in by Swanson's sister and her husband, a weaver.

A "determined and diligent boy", he is said to have learned English and the area's local Teri dialect very quickly.

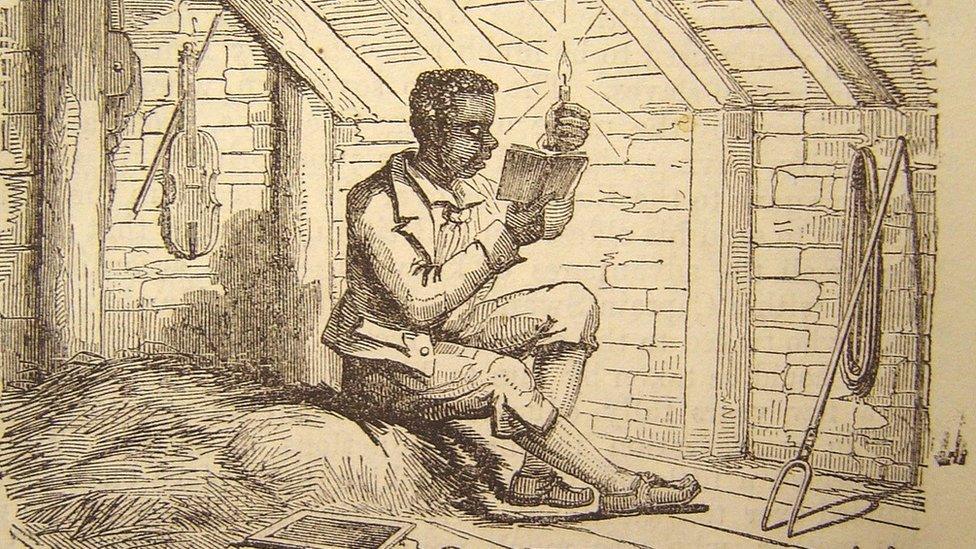

"With great willpower and alertness, Tom pored over his studies voraciously, copying each letter of the alphabet from an old book by candlelight in the loft, above the lowly stable where he lived," said Dr Monserrat.

"He avidly read anything he could get his hands on."

An illustration of Tom Jenkins reading by candlelight

At the age of 20 he applied to become schoolmaster at Teviothead, but was initially prevented from doing so.

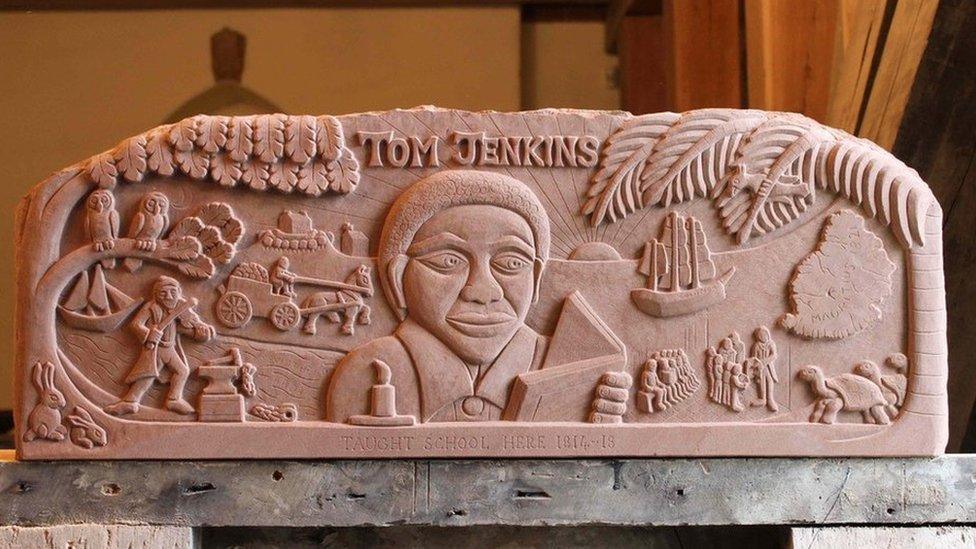

"His aptitude for teaching, however, was so apparent and brilliant that the likes of the fourth Duke of Buccleuch and other local patrons put funds together to convert the village smiddy into a school," said Dr Monserrat.

There is a small plaque in his honour on the building, which is now the Johnnie Armstrong Gallery.

"Tom's passion for learning and his wonderful flair for teaching began and blossomed in Hawick," said Dr Monserrat.

Thanks to local support, particularly from the Quakers, he went on to study at the University of Edinburgh.

A lintel in the old blacksmiths also commemorates Jenkins' work

In 1821 he was posted to Mauritius, where he ran a school. He never set foot on British soil again, and died on 16 June 1859.

Dr Monserrat will deliver a keynote address at the Alchemy Festival and show work she has made over the past six months as its artist in residence.

She hopes this can raise awareness of Jenkins' story.

"It's clearly not very well known, I don't think there's any sort of published book that he is acknowledged in that I've been able to find," she said.

"He clearly set the tone here."

She said Jenkins was a "one man show" teaching the local children, and had been supported by wealthy patrons and people with "incredible status".

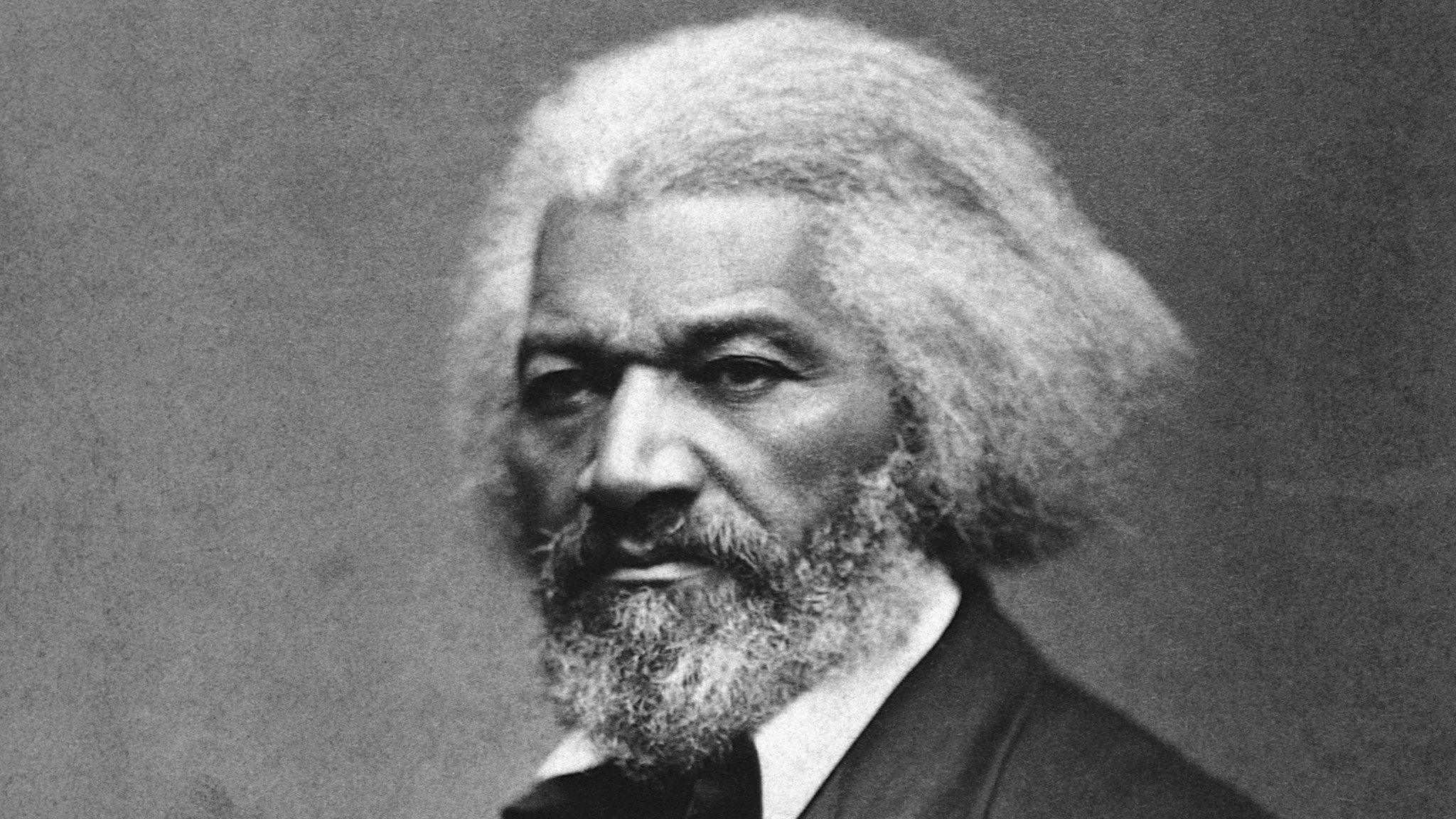

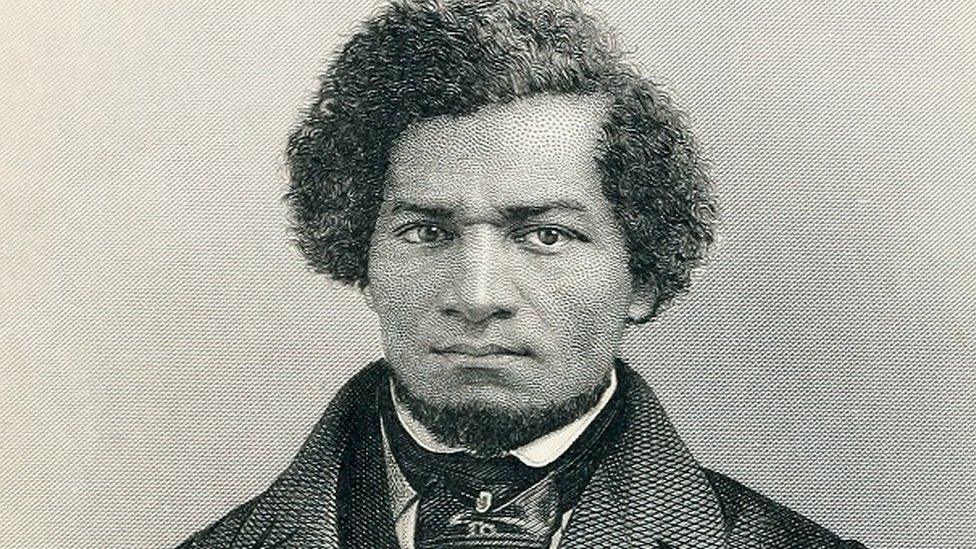

Frederick Douglass visited Hawick about 30 years after Tom Jenkins left the area

Dr Monserrat believes that the respect he commanded helped pave the way for Frederick Douglass to be accepted when he visited Hawick to deliver a speech about 30 years later.

However, she said there was still work to be done in giving both men the recognition they deserved.

"I think that combined these stories of two black men that made these huge contributions to the town go unrecognised whilst we do recognise colonisers, industrialists who are white," she said.

"We need to really champion and celebrate diverse stories in our rich histories.

"There is a probably a call for something that's visible that recognises Thomas Jenkins."

In the meantime, though, she aims to put his story centre stage in the area where he made history.

Related topics

- Published24 May 2021