Dr John Rogerson: The Scot trusted by Catherine the Great

- Published

John Rogerson is captured in this portrait from the National Galleries of Scotland

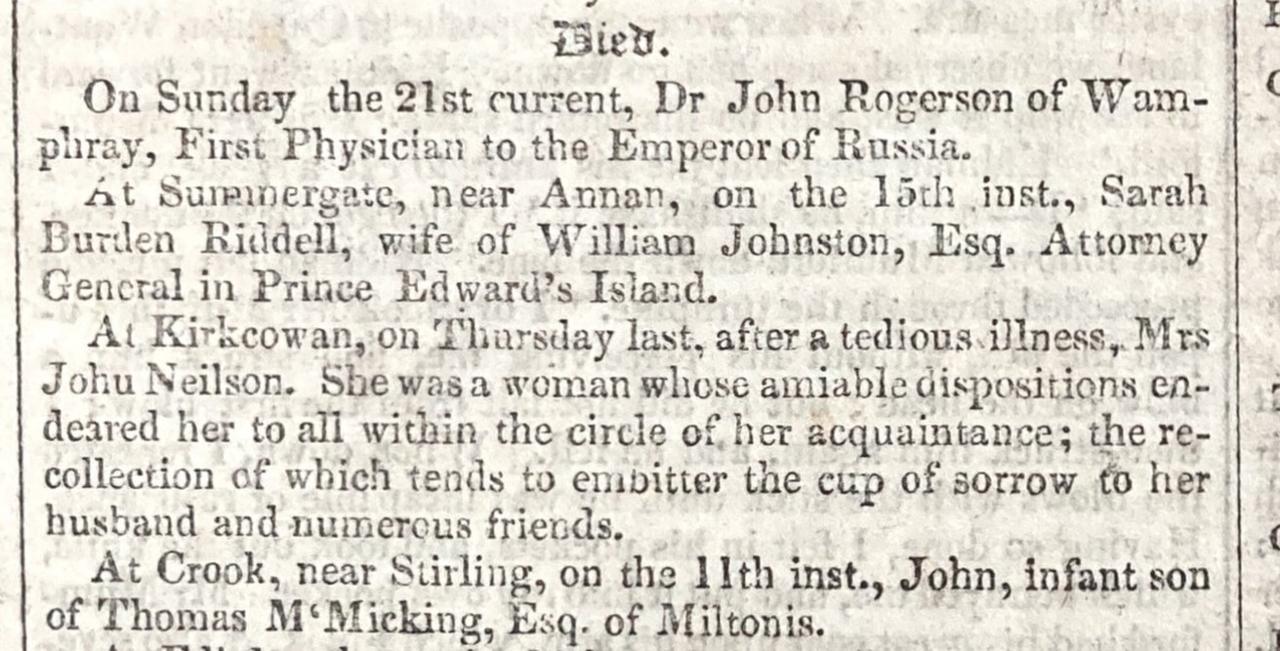

When John Rogerson died 200 years ago - just a few miles from where he was born - it barely troubled some local papers.

A couple of lines in the Dumfries Weekly Journal only briefly noted how he became entrusted by one of the 18th Century's most significant figures.

The farmer's son from Lochbrow near Lochmaben rose to become a physician and adviser to Catherine the Great.

He was a trusted confidant of the empress of Russia for a large slice of her reign.

Rogerson's death did not make big headlines in the local press at the time

Born in rural Annandale, Rogerson went to Moffat Grammar School and received his medical training at the University of Edinburgh.

Local connections, however, meant he would pursue a career much further afield.

Rogerson had dedicated his university thesis to another south of Scotland doctor who he was related to, James Mounsey, who worked in Russia.

It was on his recommendation that Rogerson gained employment overseas.

In 1766, he arrived in St Petersburg and subsequently received the right to practise in Russia.

"It was not long before he earned the respect and gratitude of the Russian royal family by saving the life of Princess Dashkova's son who had a severe episode of croup," said Jim Storrar in his Moffat Bedside Book.

Rogerson came back to Dumcrieff House - near where he was born - after his time in Russia

By 1769 he was appointed court physician but his role appears to have been much wider than that.

"Although Catherine professed scepticism towards doctors and medicines, she seems to have regarded Rogerson as the most capable physician in her entourage and often dispatched him to deal with emergencies or to treat her sick friends," said his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

"Rogerson was reputed to be absent-minded, a passionate gambler, and a gossip.

"These characteristics, together with his tall and angular appearance, made him the butt of jokes.

"Nevertheless, he possessed sufficient tact and diplomatic skills to be used regularly in unofficial negotiations, and acquired many staunch friends, among both Russians and foreigners."

Who was Catherine the Great?

Catherine II was Empress of Russia for more than 30 years and one of the country's most influential rulers.

She was born in Stettin - then part of Prussia, now Szczecin in Poland - the daughter of a minor German prince.

In 1745 she married Grand Duke Peter, grandson of Peter the Great and heir to the Russian throne.

He became Tsar Peter III in 1762 but was soon overthrown - and killed shortly afterwards - and Catherine declared empress.

Her major influences on her adopted country were in expanding Russia's borders and continuing the process of Westernisation begun by Peter the Great.

She read widely and corresponded with many of the prominent thinkers of the era, including Voltaire and Diderot and was a patron of the arts, literature and education.

She died in St Petersburg on 17 November 1796 and was succeeded by her son Paul.

Source: BBC History.

Rogerson's influence brought him a gift of an estate in the Minsk region which added to his already considerable earnings.

"He became a close friend of the empress, who appears to have preferred him as a friend and adviser than as a physician," according to the book Scotsmen in the Service of the Czars.

"She treated Rogerson as a kind of Moliere charlatan: 'You couldn't cure a flea-bite!' she would say to him."

One area where his discretion appears to have been valued, however, was in reputedly checking her lovers for sexually transmitted diseases.

"This gave him access to many court secrets, which remained such in his canny keeping," it was reported.

Despite Catherine's death in 1796, Rogerson remained in Russia and was promoted to the rank of "secret councillor" under Paul I.

After Paul's assassination in 1801, the Scottish doctor helped Empress Maria Feodorovna to escape while carrying the future Tsar Nicholas I to safety.

He continued to work in Russia until 1816 although he regularly visited his homeland.

"He also sent many delicacies home to his family in Scotland," wrote Storrar, "such as salted cucumber and reindeer tongues."

On returning to southern Scotland, he settled on his estate in Dumcrieff where a new house was completed in 1821.

He would die there on 21 December 1823, aged 82, having lived a life that his death notice hardly did justice.

Listen to news from Dumfries and Galloway, follow the BBC for the south of Scotland on X, external or send your story ideas to dumfries@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published12 July 2012