Dundee scientists say molecule key to cell development

- Published

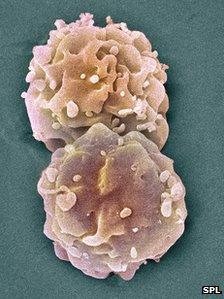

The team are trying to understand how cells become more specialised despite starting the same.

Scientists in Dundee believe they have uncovered a key step in how cells turn into tissues and organs.

Researchers at the University of Dundee have identified a molecule that could help them understand how cells start the same but then become more specialised.

The College of Life Sciences have identified a 'signal' molecule.

Called "cyclic-di-GMP" it helps determine what type of cell it differentiates into.

The university's Schaap laboratory studied a simple multicellular organism, Dictyostelium, in which motile cells (those which can move spontaneously) differentiate into two immobile cell types: stalk cells and spores.

The team, led by Professor Pauline Schaap, found the molecule could trigger the development of stalk cells.

It builds on earlier research where the laboratory found a molecule that induces the differentiation of spores.

Remarkable findings

Professor Schaap said: "Our work presents the opportunity to fully understand how cells learned to become different from each other in early multicellular organisms."

"These findings are also remarkable because cyclic-di-GMP was previously only found in bacteria, where it causes bacteria to lose motility and transform into large sticky colonies, known as biofilms.

"The fact that an organism like Dictyostelium, which is very far removed from bacteria, uses the same mechanism is very interesting and suggests that the processes which cause cell differentiation in eukaryotes, like ourselves, may have very deep evolutionary origins."

The new research has been published in the journal Nature.

- Published18 July 2012

- Published10 July 2012

- Published14 May 2012