'The Queen of Okoyong': The legacy of Mary Slessor

- Published

Mary Slessor's compassionate approach is credited with changing how missionaries did their work

Scots missionary worker Mary Slessor, who died 100 years ago on 13 January, worked tirelessly to improve the lives of ordinary citizens of Calabar, Nigeria.

To begin with, Mary Slessor was every inch the Victorian missionary, seeking converts to Christianity amid the African jungle.

When she first arrived in Nigeria, she described the local people as "heathens".

But as she settled into life among the ordinary people of Calabar, her attitude quickly changed - and not only did she change, and save, lives in the city and beyond, she changed the whole meaning of missionary work and how to serve the church abroad.

Born in Aberdeen and raised in Dundee, today Mary Slessor's face is immortalised on the £10 Clydesdale bank-note, but according to the Mary Slessor Foundation, few in Scotland are aware of the extent of her deeds.

They plan to change that with a packed calendar of events around the centenary of her death, including the unveiling of a monument bearing her name in Dundee city centre.

Religious inspiration

Slessor's early life in Dundee was a difficult one. Her father was an alcoholic, who eventually died of pneumonia, and Mary effectively became the family's main breadwinner, working 12 hours a day in a jute mill.

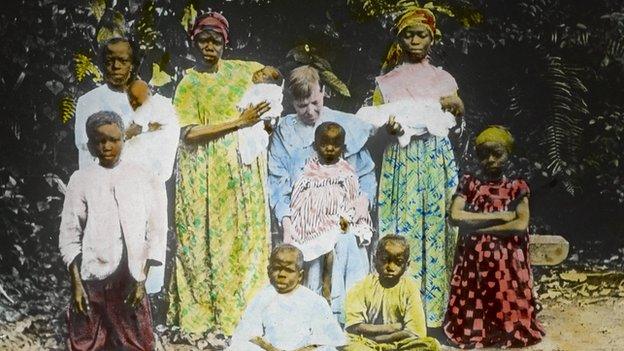

Her red hair and blue eyes made Slessor instantly recognisable among the tribes of Calabar and Okoyong

However she was inspired by her mother's strong Presbyterian faith and longed to follow in the footsteps of famed missionary and explorer David Livingstone and spread the word of God abroad.

In 1876, at the age of 28, Slessor set sail for Nigeria aboard the SS Ethiopia.

She held a number of positions at missionary compounds in the city but only managed to get herself deployed deeper into the city following an enforced leave of absence back in Scotland after she had contracted malaria in 1879.

At her new posting, instead of staying in the missionary compound, Slessor spent far more time among the people of Calabar, first learning to eat their food - she could hardly afford to feed herself, she sent so much of her wages home - and then learning the local language.

With her red hair and blue eyes, she was instantly recognisable to the local people, who came to trust and even revere her for the tireless fight she put up on their behalf.

'Remarkable woman'

Rt Rev John Chalmers, moderator of general assembly of Church of Scotland, is to visit Calabar this year to see at first-hand the difference Mary Slessor wrought.

"She was a remarkable woman in her time," he said.

"There was a very strict regime, a strict dress code and a manner in which the work of missionaries had to be carried out.

"What was different about Mary Slessor was that she realised that in order to be effective she had to break some of those moulds.

"She saw that there were great injustices, issues she felt were detrimental to the way women and children were treated in society.

"She saw it wasn't some dominant force that would change things but getting down beside people and learning their language, not being in a distant missionary house but living with them,"

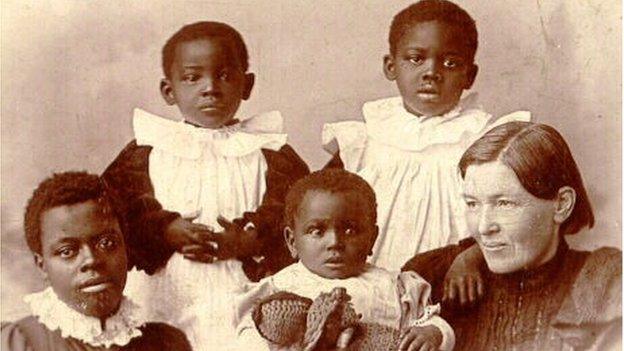

Slessor took in hundreds of sets of twins who were left to die due to local superstition

One injustice in particular which pained Slessor was the local superstition around twins.

It was held that when twins were born, one of them was possessed by an evil spirit.

Because no-one could tell which of the twins was the evil one, both were often abandoned or killed, and their mother ostracised.

"Mary Slessor realised it would take a generation of cultural change to bring about a difference," says Mr Chalmers.

"She worked right down at a grassroots level, adopted these children, saved their lives, and showed by example what needed to change."

Slessor saved hundreds of twins who had been left in the bush to die, including Janie, a girl she took in as her daughter, going as far as to bring her home to Scotland with her.

'Queen of Okoyong'

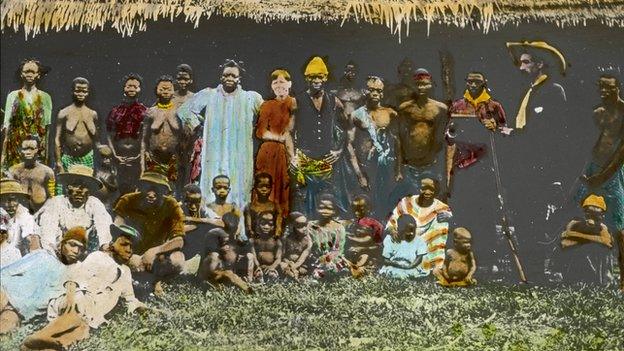

On a further mission to Nigeria in 1888, Slessor embedded herself among the Okoyong and Efik peoples for 15 years, in an area previously thought too dangerous to work in after previous male missionaries were killed.

Living in a traditional house alongside the native people, Slessor became vice-consul of Okoyong, presiding over the native court, and became known at home as the "white queen of Okoyong".

Slessor often set herself up in remote areas other missionaries were afraid to visit

Carly Cooper, a curator at the McManus, Dundee's art gallery and museum, looks after a collection of Slessor's possessions and papers, which lay bare the change the missionary underwent in Calabar.

"When people think of missionaries they don't tend to think very positively about them but she was very different," she said.

"It wasn't completely about religion for her - it was at the start, when you look at her letters she sent back, she was very much the Victorian missionary, she would talk about 'the heathens'.

"But as time went on she learned their language, their cultural traditions and there was definitely a change - it wasn't all about converts, she actually had very few people who converted to Christianity, it was about improving people's lives."

'New missionary kind'

When she died, in 1915, Slessor was honoured with an elaborate funeral, with senior British officials attending in full uniform and flags flying at half mast at government buildings.

Revered to this day by the Efik peoples in Calabar, Mary Slessor's legacy became one of mercy, rather than religious conversion.

"She didn't just take with her these Western values - she wore the same clothes as the locals wore, lived beside the people, learned their language and spoke to them in their tongue," said Mr Chalmers.

"That's what made her different - in many respects perhaps the first of a new missionary kind, not just importing stuff from this country but being sensitive to the culture and the needs of the people there."

"Her legacy is that you can't just take your beliefs and standards and values abroad and dump them on people.

"If you're really interested in people's lives and making them better, you have to understand where they come from. You have to understand them as people and love them as people, and that's what Mary Slessor did."

- Published24 June 2013

- Published2 November 2011