The awakening of Mackintosh's sleeping giant

- Published

The room begins to take shape

For almost 50 years, a store room in the Kelvin Hall has been home to Glasgow Museums' sleeping giant.

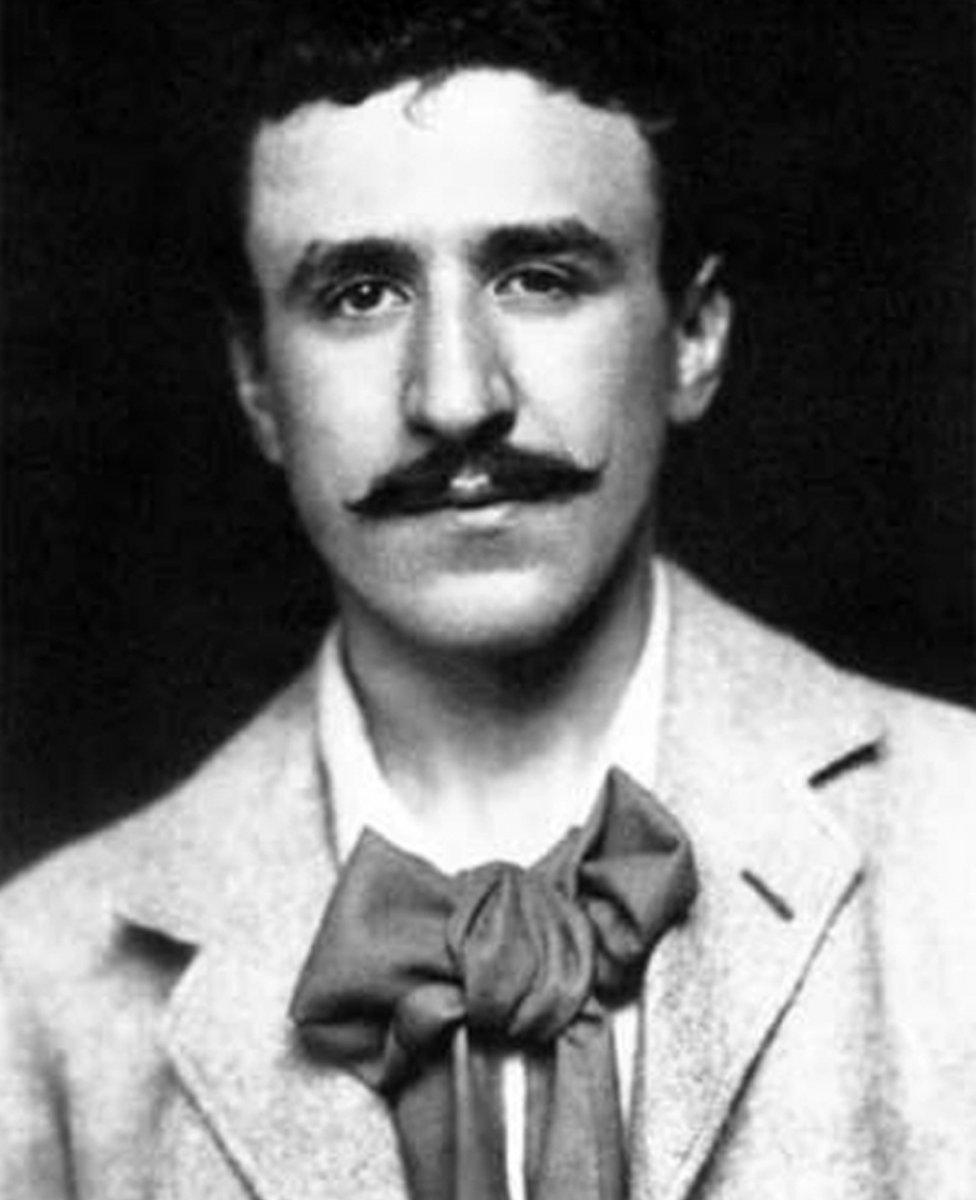

Carefully taken apart and flat-packed, an entire room of Charles Rennie Mackintosh's best work lay untouched.

But now the Oak Room from Mrs Cranston's Glasgow tearoom has been gently woken by a team of experts.

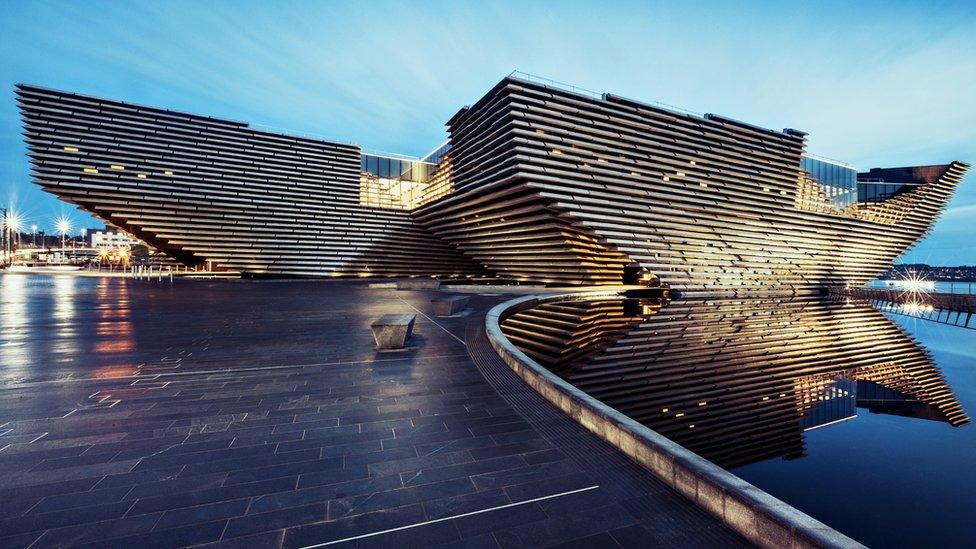

And the restoration of the room will form the jewel in the crown of the V&A's Scottish Design Galleries when the museum opens its doors in two weeks.

Glasgow Museums curator Alison Brown said: "The oak room is a sleeping giant in our collection. It is the largest tearoom interior designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh for Miss Cranston's Ingram Street tearoom.

"He was working on this at the height of his career, designing it in 1907, completed in 1908."

The journey of the conservation to the point of displaying this interior has been a long and very painstaking project, which has further revealed the intricacies of Mackintosh's design process.

It has involved very specialist crafts people and experts, almost all based in Scotland.

Charles Taylor assembled the giant 3-D puzzle in his workshop

The restoration was all about attention to detail

The process began in Midlothian.

Charles Taylor runs the wood workshop where the 43ft (13m) high Oak Room was initially restored and rebuilt.

He said: "Our workshop is in a former church in the centre of Dalkeith. It is a substantial building and it was just big enough to house the entire assembly of the Oak Room.

"The first step was to take some 850 pieces and to set out the room and it formed a massive 3-D jigsaw puzzle."

The Oak Room

Catherine Cranston was the tea room queen

Charles Rennie Mackintosh designed for Catherine Cranston

The Oak Room was the largest Charles Rennie Mackintosh interior for Miss Cranston's Ingram Street Tearooms in Glasgow.

The 44ft-long (13.5m), double-height room, designed by Mackintosh in 1907 and completed in 1908, is acknowledged as one of his key works, informing his design ideas for the Glasgow School of Art Library, which was completed a year later in 1909.

The Oak Room was last used as a tearoom in the early 1950s.

When the tearooms were removed from their original Ingram Street premises in the 1970s, each room was numbered, each wall given a reference, and each piece of panelling coded.

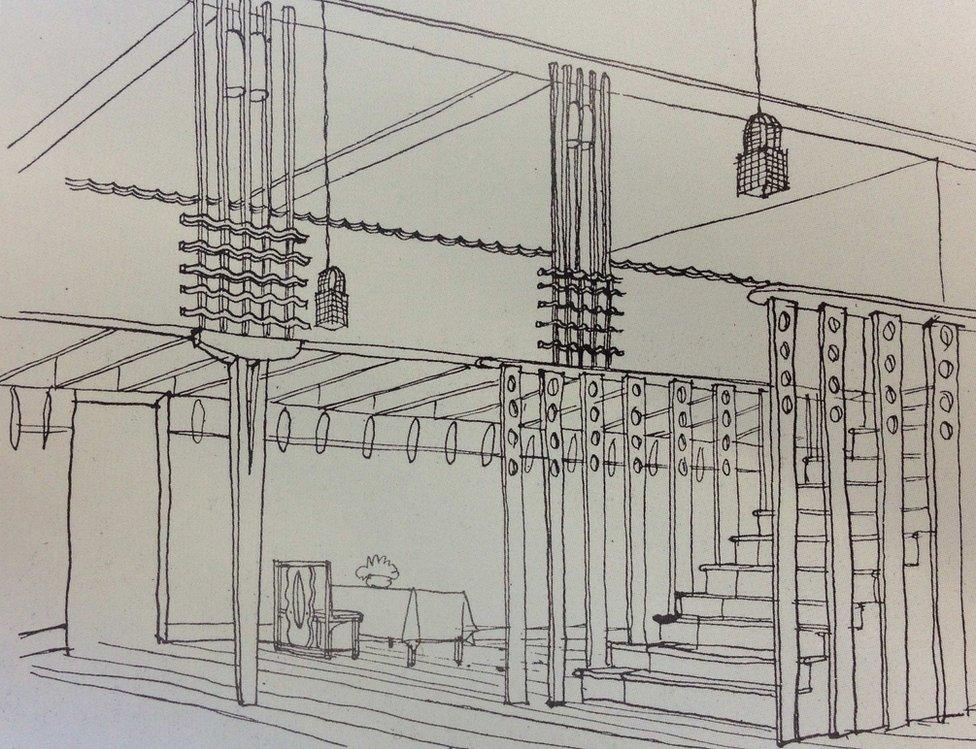

Sketches were made to help place the pieces

Models helped place all the precious pieces

Plans and elevations of the rooms were drawn to show how everything fitted together.

Between 2004 and 2005, with the help of this information, Glasgow Museums quantified and documented all surviving Oak Room panelling.

This earlier developmental stage, funded by the Scottish Government, helped inform the work to recreate the interior, lost to public view for generations.

Saved from demolition to make way for a hotel in 1971, the original rooms had already been hidden under layers of paint in the 1950s.

Charles Taylor explained: "There was clearly a big spring clean and they decided to brighten up the room, which was covered in a bright grain finish.

"That in itself was an asset, because it provided all the marks to position the pieces back to precisely where they were."

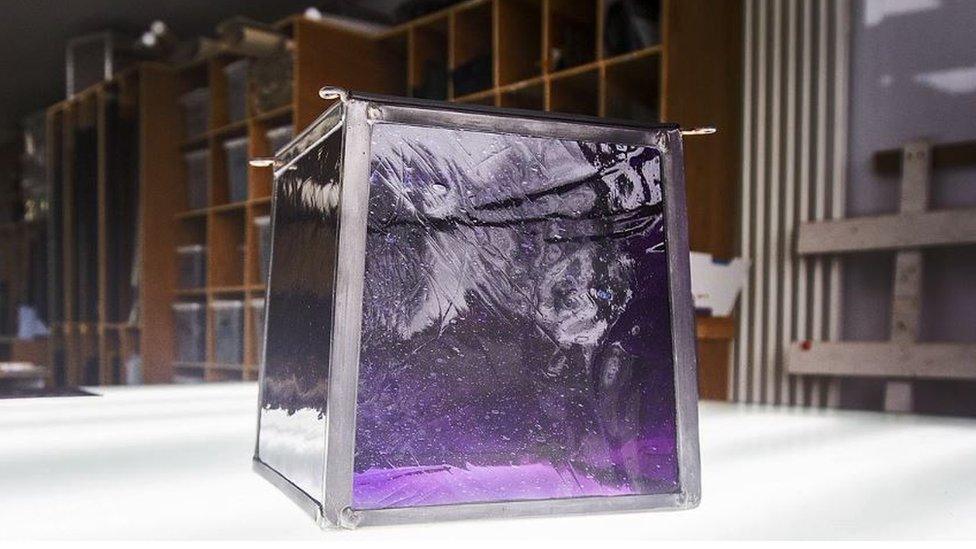

The distinctive glass was recreated at Rainbow Glass studio

The lampshades were simple but effective

Also discovered beneath the layers of paint, was the distinctive pink glass Mackintosh had used.

Moira Malcolm, director of Rainbow Glass Studio, had the challenge of recreating it.

She said: ""He chose this pink-purple streaky glass and the lampshades were actually the most simplistic design he possibly could make. They are really just four segments of glass boxed together.

"So, really, it was just showing, finding beautiful materials, made well in a simple design to maximum effect."

'Poignant and important'

To many, the Oak Room is Mackintosh's lost masterpiece.

The direction he develops here, is further developed in the Glasgow School of Art Library.

Its loss in the fire of 2014 makes this restoration more poignant and more important.

It's been a long process involving many different partners.

And they can't wait to see their work on public display for the first time in decades.

- Published6 August 2018

- Published18 January 2018