Ruins may have been illicit whisky distilleries, say archaeologist

- Published

Wee Bruach Caoruinn is believed to have once been an illicit distillery

Two ruined farmsteads found in a Scottish forest may have been an illicit distillery, experts claim.

Archaeologists surveyed the 18th century remains in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park in advance of trees being harvested.

They say the results suggest the Wee Bruach Caoruinn and the Big Bruach Caoruinn, near Loch Ard, were used to make whisky.

Strict laws led to widespread illegal whisky distilling in the 1700s.

The site was flagged up to Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) by a local history society.

Matt Ritchie, the FLS archaeologist responsible for investigating the site, said: "The surviving narrow buildings are unusually long, and are associated with two large corn drying kilns.

"Set in a relatively inaccessible area yet close to Glasgow, in close proximity to water and with strong associations with a number of the important families in the district, it is possible that the site was a hidden distillery, producing illicit whisky in the early 19th century."

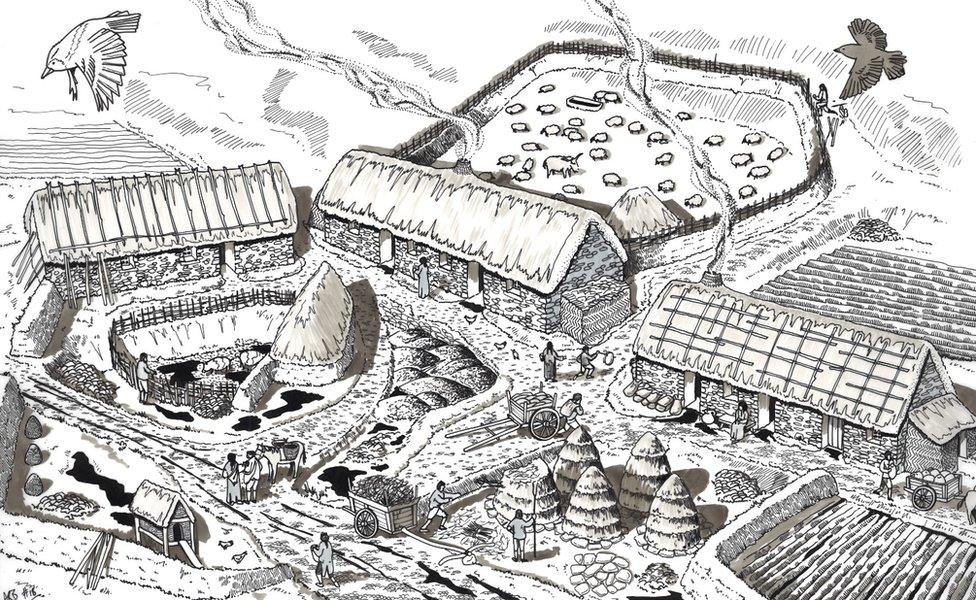

An artist's impression of Wee Bruach Caoruinn shows what it may have looked like as a distillery

About this time, illicit distilling was rife in the Highlands. The government was trying to control whisky production, and the 1788 Excise Act banned the use of stills making less than 100 gallons (450 litres) at a time.

Excise officers could search for illegal stills and confiscate the drink and equipment they found.

Legal whisky was poor quality, due to the high taxes imposed on the malted grain used to make it. Some distilleries cut corners by using unmalted raw grain, to make a drink called "corn spirits".

But because the illicit stills paid no tax, and could use good malted grain, their whisky could be smuggled to markets where it would fetch a higher price than that made by the licensed distilleries.

Mr Ritchie said: "You can malt grain in a corn-drying kiln, and the long narrow buildings would have been perfect for fermenting and distilling whisky.

"I wonder if there had been illicit whisky being made at Bruach Caoruinn on an almost industrial scale. There is no surviving evidence, bar historical whispers."

The farms were abandoned in the 1840s. By the 1860s, they had fallen into ruin.

However, the narrow roofless buildings have survived "surprisingly well" - having been given some protection by the surrounding forest.