The day Winston Churchill lost his 'seat for life'

- Published

Winston Churchill pictured in Downing Street in September 1922

One hundred years ago today, in Dundee's Marryat Hall, a pensive Winston Churchill waited for the result of an election for what he had once described as a seat for life.

He was soon to find out that this was not the case.

In his time as a Liberal MP for the city over the previous 14 years, Churchill had both received rapturous receptions and been heckled and harangued.

But his support in Dundee had started to wane since an emphatic election victory in 1918.

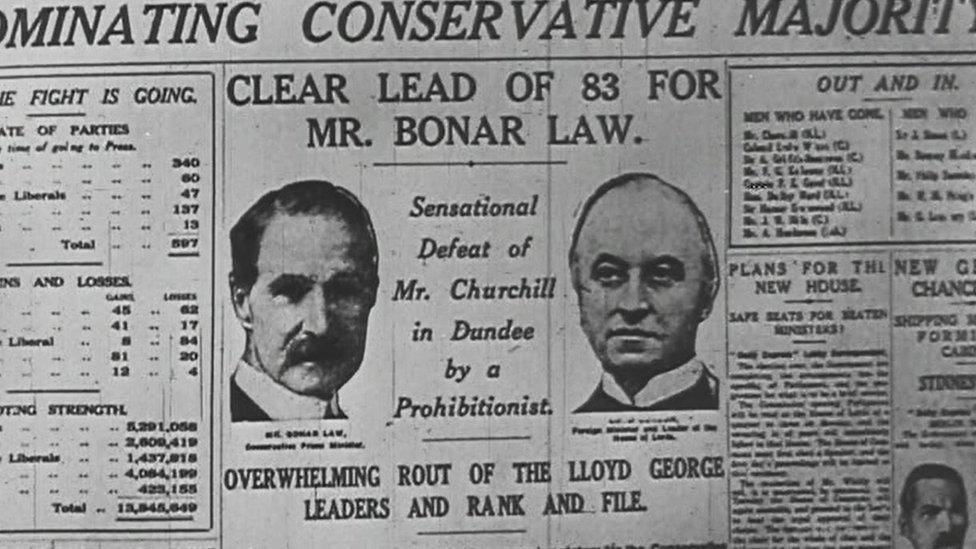

In 1922, he faced five candidates in the two-member constituency. They included the prohibitionist Edwin Scrymgeour, who ultimately claimed victory along with Labour's ED Morel.

Churchill had to be carried in a chair to the Dundee polling station after suffering from appendicitis

Andrew Liddle - the author of Cheers, Mr Churchill!: Winston in Scotland - said his 1922 election campaign got off to a poor start.

Churchill had suffered an attack of appendicitis and had to be carried into the Caird Hall on a chair with wooden handles attached.

Mr Liddle said: "That meant that he was unable to physically campaign in the city until the last four or five days of the campaign itself.

"His wife, Clementine, did come and campaign very ably in his stead.

"But that did put Churchill at a disadvantage, not being able to physically be present in Dundee."

The author said a number of factors played a part in Churchill's defeat.

Author Andrew Liddle said Churchill had a closer relationship with Dundee than many people assume

"There were also issues maintaining his electoral base in the city, which had been made up of the Irish Catholic and working class vote," he said.

Churchill's attitude towards Ireland and Bolshevik Russia badly damaged his relationship with these voters, along with limited female suffrage, which Churchill later said had "altered the political character of Dundee".

Dundee may have saved Churchill's career in 1908, but his support in the city had waned by 1922.

Mr Liddle said: "There's also the national factor.

"Churchill was a member of the Liberal Party at this time, but there were two competing Liberal parties fighting against each other."

He said he believed Churchill's relationship with the city was more complex than many imagined.

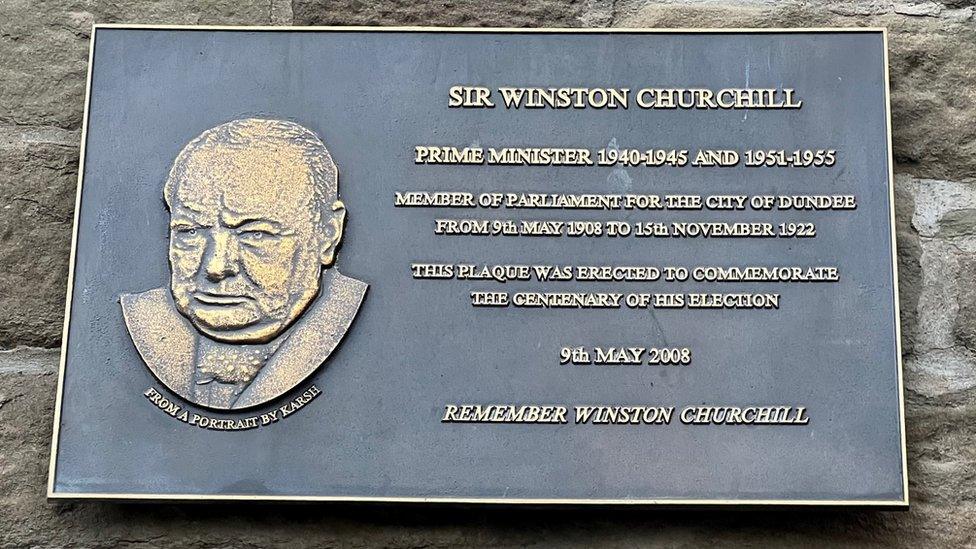

A plaque in the city centre commemorates Churchill's time as an MP in the city

"Churchill did have a successful electoral record in Dundee," he said. "He won a substantial majority in 1918 and won five elections here.

"He was a very progressive, radical Liberal politician, and had an agenda that chimed with many of his constituents.

"He didn't visit the city as often as some people would like.

"He came a couple of times a year for big set piece speeches, but that was fairly common for MPs of his era."

But Churchill did not always enjoy the warmest of receptions when he did venture north to Dundee.

During the 1908 by-election, suffragette Mary Maloney rang a large bell whenever Churchill tried to speak in public.

Mr Liddle said: "That was particularly the case during the 1922 election and in one incident in the Drill Hall in the city, he was actually completely shouted down and had to leave the event.

"But it would be wrong to think that that was universally the case.

"Churchill did, on occasion, get extremely rousing receptions in Dundee, but in 1922 it was very difficult for him."

Suffragette Mary Maloney rang a bell to disrupt Churchill's campaigning in Dundee in 1908

Winston Churchill went on to lead Britain through World War Two and returned to Downing Street in 1951.

He died in January 1965, aged 90.

Mr Liddle said there were some misconceptions about Churchill's view of Dundee after his defeat.

A quote had been attributed to him which apparently stated: "The grass would grow green through its cobbled streets, and the vigour of its industry shrink and decay."

But the author said he had found no evidence that Churchill had said those words.

However, he did give a speech in the city's Liberal Club, hours after the election defeat.

In it he said: "All my life I will look back with feelings of the deepest regard for Dundee and for those in it who stood faithfully by me."

Churchill's defeat in Dundee made national headlines

Mr Liddle believes Churchill had a stronger and closer relationship with Dundee than many people assume, despite never returning to the city.

He said: "I think that was more to do with the fact that he left a Liberal Party and rejoined the Conservatives, than any animosity he might have felt towards Dundee itself."

Churchill also rejected the Freedom of Dundee when it was offered to him in 1943.

"He was actually acting on the advice of his Secretary of State for Scotland at the time, Tom Johnston, a Labour MP," Mr Liddle said.

"He told Churchill not to accept the freedom of the city because it wasn't offered unanimously.

"So I think there are more nuances than perhaps people first imagine when it comes to Churchill's afterlife with Dundee."