Doctors gave me a pacemaker when I was 11 days old

- Published

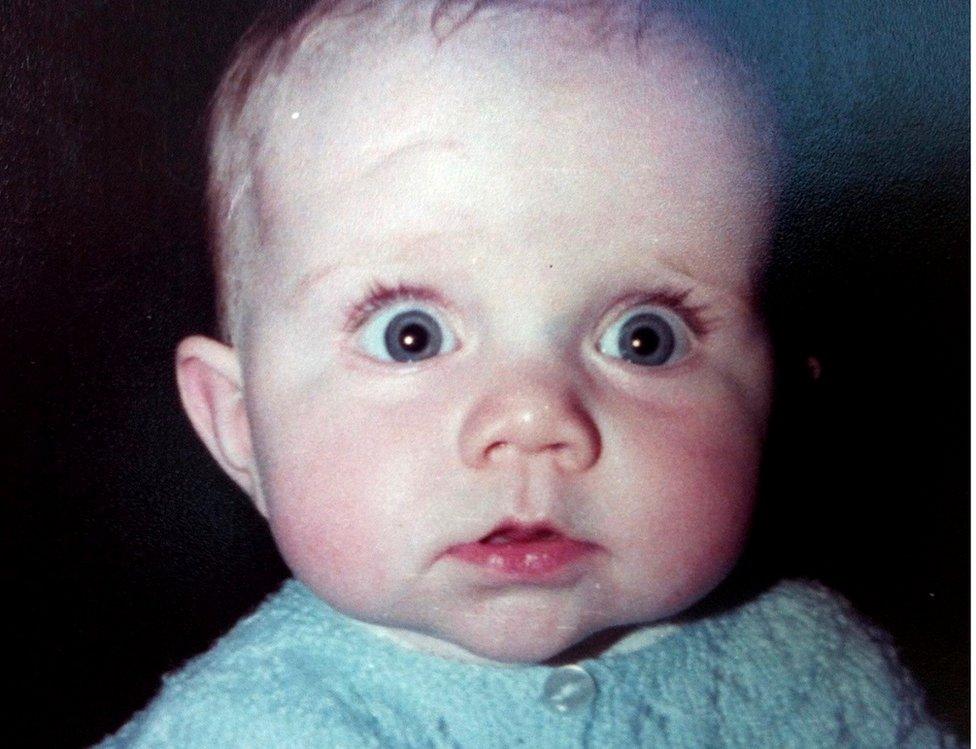

Since she was 11 days old, Liza Morton's every heartbeat has been artificially generated by a pacemaker.

In 1978 doctors decided to try and fit a bulky battery device inside her as a young baby after she was born with congenital heart disease.

It saved her life.

More than 44 years and 11 pacemakers later, Dr Liza Morton is still here.

"I was born in Bellshill maternity hospital in Lanarkshire and was moved to Yorkhill children's hospital because I quickly deteriorated," she told BBC Radio Scotland's Mornings with Kaye Adams programme.

"They fitted me with an external pacemaker at four days old which turned me from blue to pink.

"So they decided there was nothing to lose and they would try to fit a pacemaker.

"Back then it was basically just a battery, quite a big bulky one. They fitted that by bursting open my ribs and putting it onto the heart."

The first battery broke, Liza had a stroke and then she had to go back into theatre to have it fixed. It was the second of many operations.

Liza was diagnosed with congenital heart disease at four days old and fitted with a pacemaker at 11 days old

Every time she went under the surgeon's knife, nobody knew if she would survive.

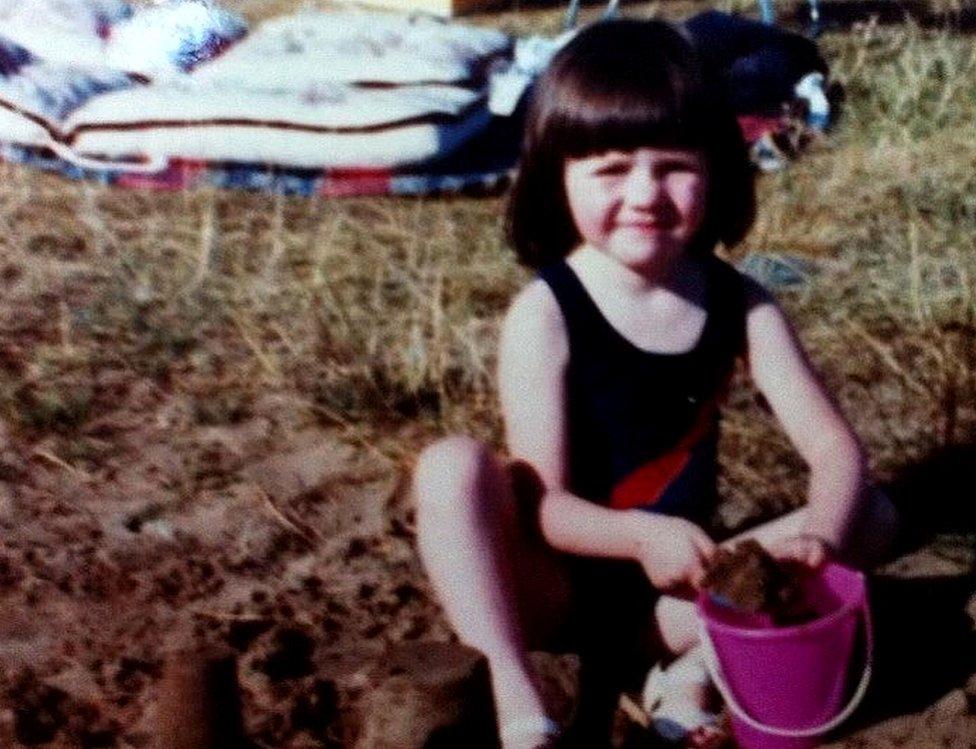

By the age of seven, Liza was on her fifth pacemaker. Each one was put in via thoracotomy - opening the chest - so her childhood was spent in and out of hospital undergoing major surgery.

She said: "I remember Mr Brewster the physicist came in from Glasgow University with a big magnet to teach the team how to adjust the settings on this pacemaker.

"They would go through this big manual trying to figure out what to do and I spent hours counting the holes in the ceiling tiles with my mum by my side. It was quite an unusual start in life."

Liza calls her treatment in the late 70s and early 80s "experimental". She and her family grew up knowing that she was lucky to be alive, that survival was tenuous.

Her teenage years brought more anguish.

Until then, her pacemakers were always at a fixed level.

"It was quite disabling," she said. "I couldn't really exert myself.

"In those days the leads were a problem, they kept falling off - they were fragile and kept breaking.

"I couldn't exert myself because my heart rate couldn't go up and I was conscious of not doing anything jerky in case I bumped the lead off."

Liza's treatment was "experimental" throughout her childhood, she says

When Liza was 13, she had open surgery to repair a hole in her heart.

"At that age you want to fit in, and be normal, so I was hiding scars and I had to sit my standard grades wearing a heart monitor knowing I was going to have to go back to theatre," she said.

It was not until much later that Liza realised how much growing up in and out of hospital had affected her.

Disrupted education, missed schooling, feeling isolated from her classmates were the fallout from her traumatic young life.

"I ended up with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in my late teens. It was the 90s but there wasn't really any treatment so I had to live with horrific nightmares of being a child in hospital.

"I was triggered by things. Beeping noises in shops transported me back to heart monitors. The smell of antiseptic would take me back to being in theatre and even the smell of toast, because that was always the first food they gave you after surgery.

Liza trained to become a chartered counselling psychologist, and now helps people who have been through trauma due to congenital heart disease (CHD).

"Missed education, missed schooling had an impact. I only ever worked part-time. I have worked very hard to become a psychologist, partly to make sense of my own experiences and then to try to build on that work," she said.

Along with co-author Tracy Livechhi, Liza has written the book "Healing Hearts and Minds" to help others through the trauma.

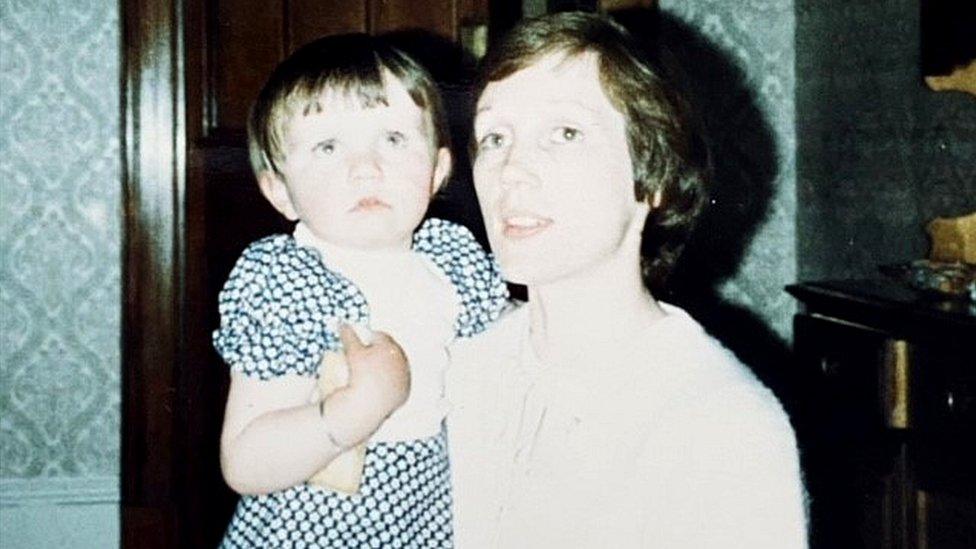

Liza Morton said she was a quiet clingy child due to her experiences

"I wouldn't say I had an unhappy childhood but there was a lot of trauma and a lot of medical trauma and that wasn't really recognised then," she said.

"I spent the first six weeks of my life in ICU, my mum didn't hold me until I was six weeks old.

"At that stage I already had scars, I had already had a stroke, so the stuff we know now about early attachment and bonding had an effect. Lots of early trauma can impact on a lot of facets of your life.

"It was very much survival-focused care back then. What we know in psychology about trauma has transformed."

Liza basically wrote the book she had been looking for herself.

"Despite being the most common birth defect affecting one in 125 live births, there is no psychosocial support - this is the first book.

"This is the book Tracey and I were looking for life-long and couldn't find.

"I sent a copy of the book to my cardiologist Dr Doig and he wrote me a lovely letter back saying 'yes you were a survivor and a pioneer and that infant cardiology back then really was a baby as well'."

And there are plenty of people who will relate to what Liza went through.

Advances in medical science mean the number of people living with CHD into adulthood has risen from 20% in the 1940s to more than 90%.

Liza said: "I just want to say to people, you are entitled to have a reaction to what you have been through.

"We give them the latest research and make it accessible and easy to read. And we give them the tools to cope."