Cardiff's 'worst night' of Blitz remembered 70 years on

- Published

Bomb damage in Clive Street, Grangetown after the raid

More than 2,100 bombs fell in the Cardiff district in nearly four years until the final air raid in March 1944. In total 355 were killed.

Across Wales, the civilian death toll was nearly 1,000 over the course of the war, with Swansea and Cardiff enduring the worst casualties.

Here BBC Wales news website speaks to three men for whom fate intervened on Cardiff's worst night of bombing during World War II in 1941.

It is 70 years since the worst night of the Blitz for civilians in Cardiff - when a bombing raid saw more than 150 killed.

The toll on the night of 2 January 1941 also saw 427 more injured, while nearly 350 homes were destroyed or had to be demolished. Chapels and the knave of Llandaff Cathedral were also damaged.

The worst hit areas were Grangetown and Riverside.

John Williams was 14 and working as a baker's delivery boy

There, casualties included an estimated 50 killed in De Burgh Street, Riverside.

Meanwhile seven relations who had been to a family funeral earlier in the day were killed when bombs wrecked Blackstone Street.

The worst single incident was at the home of a bakers, Hollymans on the corner of Stockland Street and Corporation Road in Grangetown.

Around 32 people were killed - including at least five members of the Hollyman family, neighbours and strangers - as they sheltered in the cellar. The bomb when it hit left an 8ft pile of rubble.

The 10 hour air-raid, during a full moon, had started at teatime - 6.37pm - and Grangetown was the first area to be hit by 100 German aircraft.

John Williams, a 14-year-old delivery boy for the bakery, arrived the next morning for his horse-drawn round to find his employer Bill Hollyman's baker shop reduced to rubble.

Three generations of the family were among the dead. Around 20 unknown victims were buried at the spot in a mass grave.

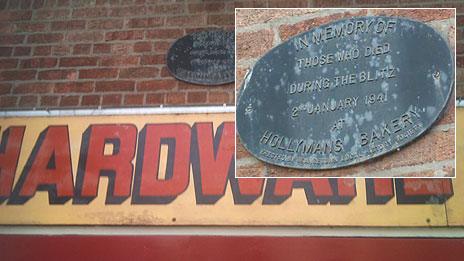

Plaque erected by Grangetown Local History Society, to remember the dead at Hollymans on the wall of the shop which replaced it

"I knew nothing about it until I got there about 8.30 in the morning," said John, now 84. "I just saw a big ruin.

"The firemen were still spraying water on it and the water had turned to ice because it was so cold. They were starting to bring the bodies out on stretchers.

"It was incredible but the horse, in the stable next door, was all right. The bomb had gone through three floors of the house and into the shelter and exploded."

"I'd been in the shelter the night before. You'd walk down a few step into the cellar, there was seats inside and steel poles put in by the corporation to reinforce it.

"I'd finish my final round about 6pm and I went down the shelter, and then was given a bowl of soup.

"But that night, Bill Hollyman seemed to think there was a lot of activity overhead and said my mother would be worried and I should go home. It was fate."

"It was a bad night. I lived in Devon Street [half a mile away] and we had an Anderson shelter at the back and I was in there with my father, mother, brother and sister.

"Luckily, the nearest bomb to us was in North Clive Street, which landed on a wholesalers and blew the slates off the roofs in the street, but we were all right."

Ken Lloyd, 12 at the time, was walking home from a children's meeting at the Ebenezer chapel in Corporation Road, when the air raid siren sounded.

"You could hear the aircraft in the distance. Mr Hollyman was standing outside, calling people, all the children and anybody passing, into shelter in the basement," he recalled.

"Quite a lot of the children who'd been at the Ebenezer went in but I only lived over in Warwick Street and so didn't have far to go so I said 'no'."

Seven people, including two brothers, were killed when a bomb hit the corner of Ferry Road and Holmesdale Street in Grangetown on 2-3 January

"I'd been with the other children that day but everyone who went into that shelter in the bakery was killed outright."

Trevor Tucker, who was six, had also been offered a place in the shelter, along with his mother and brother.

"My father's job took him away from home a lot and the baker was very helpful offering us shelter if we were alone during a raid, especially at night.

"But there was no electricity and the only light was from hand torches or candles, so I found it spooky and I told my mother, 'please don't take me there'."

He remembers, with his older brother, their fascination when watching a body being removed from the debris the next day.

Censorship meant restrictions in details of the air raids in the newspapers, with scant details and in the days to follow, few death notices were published.

The death toll in Cardiff rose to around 165 after the raid. In the days following, there was an appeal for blood donations, as the injured continued to be treated.

"A list of casualties would be posted outside City Hall," recalls Mr Tucker, now 76.

"I remember being taken there by my father... But it was the rather macabre business of seeing a list of names and him reading down to see if he had lost a friend or neighbour."

As for his own reaction to the bombing, Mr Williams said: "I just went home but you just got on with it in those days."

One of the surviving members of the Hollyman family, Jack, who lived in Canton, started up the business again within a few weeks. The bakery building itself, like John's delivery horse, had survived.

"Jack was heartbroken - he'd lost all that family," said Mr Williams.

A hardware shop now stands on the Hollymans site in Grangetown but there is a plaque on the wall, erected by the local history society, to remember those who died there.

- Published7 September 2010