Rhondda marks 100th anniversary of Tonypandy Riots

- Published

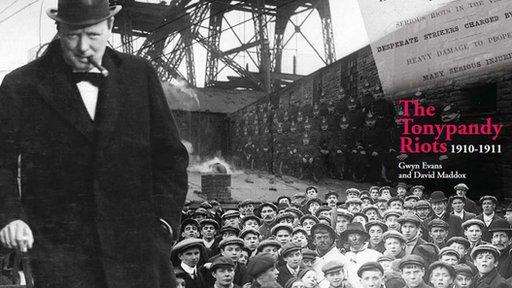

In their book, The Tonypandy Riots 1910/1911, David Maddox and Gwyn Evans, challenge some of the commonly-held assumptions about the period

A century on, and for some in the Rhondda the Tonypandy Riots remain a symbol of duplicitous coal-owners, and interference from Westminster in Welsh affairs.

On the nights of 7 and 8 November 1910, striking miners from pits owned by the Cambrian Combine laid waste to Tonypandy town centre, wrecking shops and mine-owners' property.

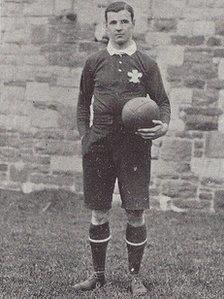

Rhondda folklore has it that the only shop spared was the chemist, because it was owned by Welsh rugby legend Willie Llewellyn.

In a move which would tarnish his reputation among many locally, the then Liberal Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, sent troops onto the Tonypandy streets in support of the police.

But as Rhondda Cynon Taf council commemorates the riots with a week of events, a new book by local historians, David Maddox and Gwyn Evans, The Tonypandy Riots 1910/1911, challenges the two most commonly held assumptions.

These are that Willie Llewellyn's shop was purposely avoided, and that the intervention of the Army was necessarily a bad thing.

On 1 September 1910 owners at the Ely Pit in Penygraig locked out 950 miners, after a disagreement on the expected rate of extraction on the newly-created Bute seam. This was despite the fact that the dispute involved only 70 of those workers.

For their part, the miners argued that it was nonsensical for them to work more slowly than the seam demanded, as they were paid per ton of coal extracted, rather than by the hour or day.

By the start of November, the strike had spread to all 12,000 colliers employed by the owners involved in the Cambrian Combine - a cartel created to fix coal prices and wages.

On 2 November a pay deal of 2s 3d per ton, negotiated by Liberal MP William Abraham, was rejected by the South Wales Miners Federation, who by this stage had successfully shut all but one of the cartel's pits.

Already stretched by a strike involving 11,000 miners at Aberdare in the neighbouring Cynon Valley, the Glamorgan Constabulary began to make contingencies for the inevitable clashes when the Cambrian Combine tried to move in strike-breakers to maintain their one functioning pit, Llwynypia.

Despite initial reservations, Churchill eventually ordered 200 Metropolitan Police officers into Tonypandy, with a detachment of Lancashire Fusiliers held in reserve in Cardiff.

It would prove a decision which damaged his reputation among many in Wales, seeing him booed at Cardiff's Ninian Park 40 years later during the 1950 general election campaign, and causing councils to block dedications of street names in his honour to this day.

Inevitable clash

On 7 November the inevitable clash between picketers and strike-breakers materialised at Llwynypia. Miners and police fought hand-to-hand, as the strikers pelted the pit's powerhouse with rocks.

Eventually they were driven by mounted baton charges, back into Tonypandy square, sparking two nights of rioting and looting.

Rioters may have spared Willie Llewellyn's chemist's because of his rugby fame

In response, the Glamorgan chief constable, Lionel Lindsay, called in the troops from Cardiff. Despite the controversy their intervention has caused to this day, in fact they did not arrive in Tonypandy until well after the rioting had begun to subside of its own accord.

Indeed, according to David Maddox, throughout the four months during which they remained in Rhondda, relations between the soldiers and miners seem to have been extraordinarily cordial given the circumstances.

"You have to remember that the story of the Rhondda riots, and Tonypandy in particular, has been handed down from generation to generation, and has altered subtly over the years."

"Our research for the book, has unearthed sources demonstrating that it was the decision to call in the troops which made the miners so bitter, not the actual presence of the troops themselves."

"In fact it seems as though the troops were very popular, particularly with the girls. It was said that every Lancashire Fusilier could sing at least two verses of Cwm Rhondda by the time they left in March.

'Stuck in the craw'

"Major-General Neville Macready instigated almost daily meetings with miners' leaders, and was given a commendation for his handling of the situation. Very few miners or soldiers were injured throughout the rest of the dispute - certainly compared with how many had previously been hurt in clashes between police and miners - and none were killed.

"The bitterness towards Churchill, which has been passed down the years, stems from the fact that the troops' presence made picketing impossible, and effectively broke the strike. It stuck in the craw of the miners, that a Liberal government would use the army to side with pit owners over the workers."

Possibly the most enduring local legend is the story of how Willie Llewellyn's chemist shop, (currently Devonalds Solicitors on the lower end of Dunraven Street), was spared damage in reverence of his rugby fame.

Llewellyn is best remembered as part of the 1905 Wales team who defeated the travelling All Blacks in Swansea, for the first, and only time. He captained his country, winning three Triple Crowns and touring Australia in 1904 as part of a combined British Isles side.

Yet David Maddox has been unable to find any evidence that it is true.

As he explains, that does not necessarily mean it did not happen. A contemporary newspaper report lists shopkeepers awarded damages, and Llewellyn's shop is not mentioned.

Final confrontation

"I have a photograph showing that Willie Llewellyn's shop was boarded up and the gas lamp outside was damaged.

"But this could have been taken on the second day of rioting, which makes me think that maybe the property wasn't damaged on the first night and realising there was more rioting to come, Willie boarded up the shop himself to protect it before the second night of violence."

"On the other hand you have to consider the locality of the shop itself. If a mob of several thousand was marching through Dunraven Street then Willie's shop was actually slightly tucked to the left. They would have to almost turn back on themselves to deliberately damage it."

Whild things calmed down after 7/8 November, skirmishes and unease remained in the area until August the following year, when the miners were forced to accept the original offer of 2s 3d per ton, and return to work.

Fittingly, the scene of the final confrontation in July 1911 was back at the Ely Pit, where the conflict had begun over ten months earlier.

The launch of The Tonypandy Riots 1910/1911 is part of a week of commemorative events organised by Rhondda Cynon Taff Council.

Other highlights include a musical interpretation of the riots by local performer Martin Joseph, and a family day on Sunday 7 November, culminating in a free concert.