Restored grave for Barry sailor who survived shipwreck

- Published

Cecil Foster learned survival lessons from his experiences in World War I

Master mariner Cecil Foster might not be a name on the tip of everyone's tongue, even in his home town of Barry.

But 88 years ago it would have been a very different story, because after a Hollywood-style escape from a shipwreck in the Indian Ocean, he became an overnight celebrity.

There were newsreel appearances, a best-selling book and even an audience with King George V.

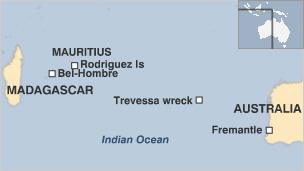

On 4 June 1923, the Hain Line steamer Trevessa, heading from western Australia and loaded with zinc concentrates, sank 1,700 miles from shore.

Foster, a master mariner, was personally credited with having led over three quarters of his crew to safety. Thirty four of the 44 crew survived a 23-day lifeboat ordeal, until coming ashore on Rodriguez Island near Mauritius.

Despite the media interest which surrounded their return home, Foster soon faded from public interest, and very little is known about his final years, until his death in Barry, aged 40 in 1930.

But now Keith Greenway, a researcher for the Merchant Navy Association in Wales, has been so inspired by his story, that he's put together the missing pieces of his life.

Mr Greenway has also traced members of the Foster family, and raised around £1,000 to restore Foster's grave in Barry's Merthyr Dyfan Cemetery.

It has been untended since his wife Minnie's death in 1982.

"It's been quite a battle really, as Cecil and Minnie didn't have any children themselves, so all the surviving relatives are cousins, second cousins, great nieces and nephews and so on," said Mr Greenway.

"Raising the money to restore Cecil's grave was much more straightforward; all I had to do was explain a little about his life, and both businesses and individuals were more than happy to get involved."

'Break down'

The son of a merchant seaman, Cecil Foster was born in Malta in 1890, and spent most of his early years in his parents' Aberdeen home, before his father's work brought them to Barry, some time before 1902.

Aged 12, he went to sea with the Hain Steam Ship Company of Barry, who had a tradition of training local children right through the ranks to eventually captain the firm's ships.

As a first officer on supply ships during World War I, Cecil was torpedoed by U-boats twice in the same day.

On the first occasion all the survivors were picked up by a passing Royal Navy patrol, only for that ship in turn to be sunk by the same U-boat, around 320 miles south-west of the Scilly Isles.

This time the 31 survivors of the two ships were adrift in a lifeboat for 10 days, before eventually washing up at Ferrol on Spain's north-west Atlantic coast.

The Trevessa was wrecked 1,640 miles west of Fremantle

Only 16 men made it to Spain alive, but the lessons Foster learnt would save 34 of his own men on the Trevessa, and hundreds of thousands of sailors involved in similar shipwrecks throughout the next century.

"Cecil Foster's time in the lifeboat during WWI taught him that the survival rations were all wrong, and that many men died, simply because they'd ceased to have anything to keep living for."

"The rations stowed in the boats at the time were very similar to the ship's usual diet. It mainly consisted of tinned and/or salted meat, which was extremely difficult to digest, and sucked out a lot of scarce water from the men's dehydrated bodies."

"After the war, Cecil insisted that Hain changed the emergency drills and rations. Salted beef was replaced with condensed milk and hard biscuits, with high calorific content but easy for the stomach to break down."

"He also placed high stock by supplies of cigarettes, and maintaining daily routines of rowing and cleaning aboard the lifeboats. If the men had a job to do, and a reward for doing it, then they had a basic function which kept them wanting to live long after an idle man would have given up."

It was in the early hours of 4 June 1923 when the Trevessa began taking on water, and sunk with such speed that many of the crew didn't even have a chance to get dressed properly.

The zinc concentrates which Trevessa was carrying from Fremantle in Western Australia to Durban in South Africa were stored in a thick ooze, and prevented use of the bilge pumps in order to bail out the hold.

The SS Trevessa was carrying zinc concentrates

So within 15 minutes of first pitching forward in the water, the Trevessa had sunk, and the crew were alone in two 26ft lifeboats.

Foster took control of rationing out the boat's water, (enough for seven pints per man), 550 biscuits, and two crates each of condensed milk and cigarettes.

Despite supplying just a quarter of a pint per man per day, he also made each man take his daily stint at rowing even though it was unclear exactly where they were rowing to.

He was able to keep a rough guide of their position by navigating via the Sun and stars, however even he appears to have been amazed when the first boat hit Rodriguez Island 23 days after the sinking.

The second boat missed Rodriguez Island, but landed at Bel-Ombre on the Mauritius mainland, three days later.

Three men had died of exhaustion and illness, one was washed overboard in rough seas, and six succumbed to drinking salt water, against Foster's strict orders.

But incredibly 34 did make it to Mauritius, and from there, home to a heroes' reception.

The Daily Telegraph wrote of the crew, "We may think with pride that our British sailors can match in daring, resolution, and loyalty those who won for their flag the realm of the circling sea"

However, the Telegraph reporter who went on to describe the Trevessa story as, "the great adventure that will live in memory the world over", would surely be as disappointed as Mr Greenway to discover that the Trevessa is now largely relegated to a footnote in maritime history.

"In 2011 it's really impossible to describe how miraculous this escape was viewed at the time; it was the single biggest news story of the year," said Mr Greenway.

Cecil Foster's family grave has been recently restored

"I suppose the closest thing you could liken it to in modern terms is the rescue of the Chilean miners last year.

"30 June, the anniversary of the second boat's landing at Bel-Ombre, is still a national holiday in Mauritius. Originally it was known as Trevessa Day, but more recently it's been broadened out to become Seafarers' Day."

"I know times change and things move on, but hopefully with his grave restored, visitors to Barry may come and spend just a minute or two thinking about the incredible achievements of Master Mariner Foster, and the thousands of merchant seaman like him, who helped to make Britain great."

He added: "It seemed that everyone knew a little bit about Cecil's life, but no-one really had the complete picture, particularly about his final years."

He said descendants would be visiting Barry in the next few weeks for a rededication of the grave.

Mr Greenway said if any local people had had any more information about Foster's life, or about the story of the Trevessa, he would love to be able to pass it onto them.