130 years since Sunday drinking was banned in Wales

- Published

Members of the congregation arrive for the Sunday service at the Saron Chapel, Ebbw Vale in August 1952

One-hundred and thirty years ago this month, William Gladstone's Liberal government passed an act which would change the culture, politics, and even the architecture of Wales, for over a century.

Sponsored by prominent Welsh nonconformists in the Liberal party, such as future Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the Sunday Closing (Wales) Act 1881 banned the sale of alcohol in Welsh pubs on the Sabbath.

It would not be repealed until 1961, when each county was charged with holding a referendum on Sunday opening, to gauge support in their particular area.

While urban districts such as Swansea, Cardiff and Merthyr ditched the ban at the earliest possible opportunity, many rural and Welsh-speaking counties held on to "dry" Sundays.

Dwyfor - now part of Gwynedd - was the last district to drop the ban in 1996.

But Robin Hughes, clerk of Pwllheli Town Council, remembers that it wasn't a particularly contentious issue, with only nine percent of the local population turning out for the referendum.

"There were those on the extremes of the debate," he says.

"People involved in tourism argued that the ban was killing pretty much the only trade in the county, while the chapels thought getting rid of it was going to destroy the moral fibre of the area."

"Most of us had mixed feelings. On the one hand people welcomed the opportunity for a pint while they were off work, but on the other it was symbolic of the death of a little bit of Welshness, that made us a unique, tight-knit community."

Welsh identity

The act was the first piece of Wales-only legislation passed by Westminster since the 1542 Act of Union, and was the first recognition in law of a distinct Welsh identity.

Hotel de Marl - the outdoor drinking club in Cardiff which made legal history

At the time more than half the people of Wales belonged to a nonconformist chapel, yet members of the Church of England still enjoyed legal and social privileges.

Thus the Sunday Closing Act was celebrated in Wales as an important step on the road to disestablishing the Anglican church and getting the nonconformist chapels recognised on the same footing.

But Sunday closing also had a variety of unexpected effects, which historian and former BBC Wales producer John Trefor thinks may have helped to shape Wales as we know it.

"It was a victory, not only for the chapels and the temperance leagues, but for Welsh identity," he says.

"There was a sense that things could be done differently here. Wales-only Education and cemetery acts came soon after, and in many respects it established the principle on which devolution and the National Assembly are based."

Working men's halls thrived when pubs were closed on Sundays in Wales

Mr Trefor wonders if there were some unintended, but beneficial, consequences to the act.

"It all came about around the same time as the first wave of Italian immigration into the Valleys. So, with the pubs shut on a Sunday, the 'Bracchi' or Italian coffee shop and ice-cream parlour, became fixed in Welsh culture as a meeting place.

"Without the coffee shop, would Dylan Thomas have been the same writer?"

He also notes that an act which only applied to public houses gave a boost to private members' clubs, which became more than just drinking establishments.

"Around this time you see the boom in workingmen's halls, a key part of which were their libraries," he says.

"So there's a new generation of self-educated working men, who start sharing their ideas and forming more effective and radical political movements and unions."

But not all private members clubs were so grand and lofty in their ideals.

In 1893 residents of Grangetown, then a village distinct from Cardiff, won a landmark court ruling after they'd dug a pit in a field, spread out a carpet, and declared themselves to be an invitation-only private members club called the Hotel de Marl.

At the time members' clubs were allowed to serve, but not sell alcohol, a rule which the ad hoc Hotel de Marl got around by laying an old newspaper on the ground, into which members could throw donations.

After taking two days to consider his verdict, the magistrate found in the Hotel de Marl's favour, ruling that they had indeed met the criteria of a members club, albeit: "A rude and elementary type but still a club, as much as the best and most exclusive in the country."

However, the Marquis of Bute, whose land the Hotel de Marl had been using, was so outraged, that he threatened action for trespass against the "members".

By then the genie was out of the bottle, as an investigation by the Western Mail, a Cardiff-based newspaper, in 1892 found 3,000 people drinking on one Sunday in over 450 illegal drinking dens, or shebeens, across Cardiff.

Licensees protested to a Royal Commission into the Act in 1889 that the illegal drinking trade was killing legitimate public houses; as after people had visited a shebeen on a Sunday, they never returned to the pub during the rest of the week.

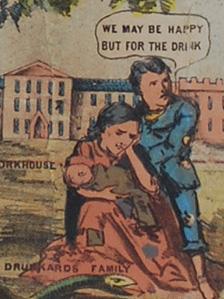

Part of a temperance poster from 1880, published in Ruabon, Denbighshire

However, while researching his book Real Heritage Pubs of Wales, Mick Slaughter found plenty of evidence to suggest that in fact the opposite was true.

"When you look for the evidence of the Sunday closing laws in the architecture of our pubs, there's two things that strike you: the number of tiny household pubs, and the number of pubs which were converted around this time, in order to offer accommodation," he says.

"Hotels, like private members clubs, were exempt from the act, but they had to have separate public and residents' bars. A lot of these have been knocked through into one today, but you can still make out the different entrances.

"It's hard to believe that there was suddenly a huge boom in tourism - especially in poor industrial areas - so you can only presume that there was some sort of fiddle going on, whereby rooms were ostensibly let out to Sunday drinkers."

"The tiny pubs are a particularly Welsh phenomenon. They started out as front-room shebeens, but went legitimate because there was far too much money to be made to risk being shut down."

"You only have to look at the amount of money poured at this time, into building some of the most famous and grand pubs in Wales, to see that drinking was big business. Making something harder to do makes it desirable."

"It's now, with all our choice and liberal licensing, that the pub is really under threat," he adds.