Llanelli's 'forgotten' riot - 100 years ago

- Published

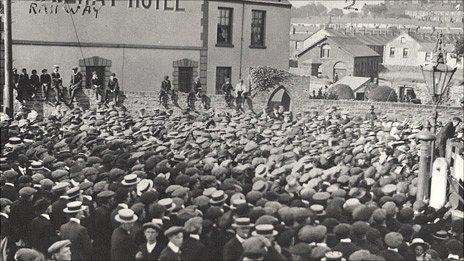

Crowds gather in Llanelli in August 1911

A week after rioting in cities in England brought headlines around the world, the story of a largely forgotten outbreak of disorder exactly 100 years ago is being retold.

What started out as a peaceful strike by railway workers in Llanelli turned within two days into violence, destruction and deaths after a bayonet charge and the shooting of two unarmed men by the army.

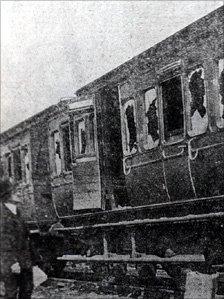

Burnt out wagons guarded by police

The railwaymen's strike had started on the afternoon of Thursday 17 August 1911, in protest at average wages of £1 per week.

These were around 20% below the norm for skilled manual workers at the time.

The strikers were joined in a show of solidarity by local colliers and tinplate workers, who enjoyed comparatively generous wages.

Around 500 men blockaded Llanelli's two level crossings, and stopped trains from passing.

Their actions were particularly politically-sensitive, as the Great Western Railway line through Carmarthenshire was the main route to and from the troubled provinces of Ireland.

In the early hours of Friday, a local councillor, magistrate and grocer, Thomas Jones, requested assistance from the military.

Several army regiments had been stationed in Cardiff, in order to quell numerous industrial flashpoints during the 1910/1914 period known as the Great Unrest.

But local historian John Edwards, who has written Remembrance Of A Riot, believes there was more to Jones's intervention than simply keeping the peace.

Bayonet-charged

"Winston Churchill is rightly reviled in Rhondda for turning troops on the Tonypandy miners in 1910, but this was possibly an even bigger betrayal as it was a locally-taken decision," says Edwards.

"Thomas Jones wasn't only a JP in Llanelli, he was also a shareholder in the Great Western Railway, and had his own financial motivation for calling in the soldiers."

Edwards says on the Friday at least, relations between the strikers and the Lancashire Fusiliers - who had experience of policing the miners' strike in Tonypandy - were very good.

There were negotiations and some trains, such as those carrying live cattle, were allowed through on humanitarian grounds.

Some of the damage to railway coaches on 19 August 1911

"Despite the fact that the Lancashire Fusiliers did an incredibly good job of keeping the peace, this wasn't enough for Thomas Jones and the GWR, they wanted the strike broken," says Edwards.

"So on the Saturday they also called in the Worcestershire Regiment, and that's when the problems really did start."

While union leaders were negotiating inside the town hall, troops from the Worcestershire Regiment bayonet-charged the crowd in order to clear the line for a passenger train.

Whilst the locomotive made it through the first level crossing, strikers pursued it, clambering aboard, raking out the fire and rendering the train immobile.

Troops followed on the strikers' heels but soon realised that they'd trapped themselves in a cutting, surrounded by stone-throwing strikers on the banks all around them.

Major Brownlow Stuart ordered the soldiers of the Worcester Regiment to open fire.

One protester was heard to call out in Welsh: "Popeth yn iawn! Blanc yw hi, bois! Peidiwch a symud, Saethan nhw ddim" (In English: "It's all right! It's blank, boys! Don't move, they won't shoot!")

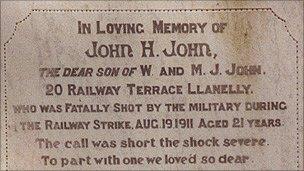

But they did shoot - and two young men, John 'Jac' John and Leonard Worsell, were killed.

John, 21, had been a promising rugby player with the Llanelli Oriental Stars. A tinplate worker, he had joined the picket line to support his less fortunate townsmen.

Londoner Worsell, just 19, had only been in Llanelli while recuperating from TB. He had nothing to do with the strike, and had simply come into the back garden, mid-shave, to see what all the commotion had been about.

The damage done, the Worcestershire Regiment were withdrawn back to the railway station.

Bitter irony

In the rioting that followed throughout the night of 19 August, shops, train tracks, the railway station and town hall were all wrecked. Thomas Jones' grocers shop came in for particularly rough treatment.

Four people died when rioters set fire to a freight wagon in sidings, not knowing that it contained explosive detonators.

Tinplate worker John John had joined the picket line in support of the railwaymen

That night the streets were cleared by a third regiment, The Sussex, who arrived in Llanelli on return from Ireland.

The bitter irony was that, by the time of the shootings and rioting, the strike had already been settled, as chairman of the board of trade, David Lloyd George, brokered an improved pay deal.

John Edwards believes afterwards, a conspiracy of silence between the local Liberal party and the chapels promoted a sense of shame about the events.

He recalls that in his own childhood, decades after the riots, his family remained reluctant to discuss what had taken place in his town.

"I can't remember if anyone ever told me not to ask about the riots, but, as a child in Llanelli, you just knew not to talk about them; it was something that the chapel frowned on," he says.

'Stories to the grave'

"Because the key figures in the chapel were also the key figures in the local Liberal party, and I guess they didn't want people looking too closely at the part they'd played in it all."

"I must have been about eight or nine when I finally started to get an understanding of what had taken place when I overheard my auntie and uncle talking about cricket of all things. My uncle asked who Glamorgan were playing that day, and my auntie answered 'The Murderers!'"

"Well 'The Murderers' were Worcestershire, because it had been the Worcestershire Regiment which had been called in to break the strike, and had killed two boys sitting on a garden wall"

Social historian Prof Peter Stead collated memories of the events 30 years ago.

"People didn't want to talk about it really, and many hundreds sadly took their stories to the grave with them. But I'm not sure that was out of a sense of shame. I think it's more that Llanelli found better and happier ways to define itself through its rugby, chapels and culture."

"But nevertheless it is a largely-forgotten piece of history, which was at least as significant as the Tonypandy Riots the year before."

"Miners already had a reputation as firebrands, but train drivers were seen at the time as steady people. They smoked pipes, served on chapel committees and tended allotments!"

"For railway workers to go on strike at all, let alone a strike which ended so bitterly and bloodily, was a much stronger indication of the depth of the resentment sweeping across industrial Britain at the time."

A documentary on the events of 1911, Llanelli Riots - Fire In The West, presented by Huw Edwards, is shown on Tuesday 16 August on BBC One Wales at 22:35 BST.

- Published16 August 2011