How 1896 Tylorstown pit disaster prompted safety change

- Published

A miner with a canary at Dinas in the Rhondda in 1965

At their height there were at least 3,000 of them employed in coal mines across the UK, and despite weighing just 15 to 20g, worldwide it is believed that they could have saved the lives of more than a million men.

That's why for a century the tiny yellow canary was the most indispensable member of any colliery's staff.

Whilst they were phased out in Britain by 1987, they are still kept as back-up to digital devices by the UK Mines Rescue Service, and remain a common sight in pits from Ukraine to China.

But even though they have spread their wings right around the globe, the inspiration for using canaries to detect dangerous gases underground started in Wales, after the Tylorstown disaster 116 years ago.

The genius behind the idea came from Prof John Scott Haldane, a medical researcher and mining engineer of Scottish, rather than Welsh descent.

His biographer Prof Martin Goodman said: "Professor Haldane was truly a giant of his age, who could only really have existed in a Victorian era before ethics and health and safety."

Prof Goodman said virtually everything we know about the workings of lungs came from Prof Haldane, who became very personally involved in the research.

Throughout the late 19th Century it was believed that most miners trapped in an explosion died from the force of the blast itself.

Prof Haldane stood virtually alone in his belief that suffocation was a far greater killer.

So from late 1895 the professor was on high alert, bags packed at Oxford University, waiting for the opportunity to test his theory at the next underground disaster.

It came soon enough, on the morning of 27 January 1896, when rock blasting at Tylorstown No 8 Pit in Rhondda Fach ignited a methane explosion so powerful that it blew the winding gear off the top of the shaft.

Palls of poisonous gases and lightning storms hampered the rescue attempts, so that it was well into Tuesday by the time the final death toll of 57 men and 80 pit ponies had been arrived at.

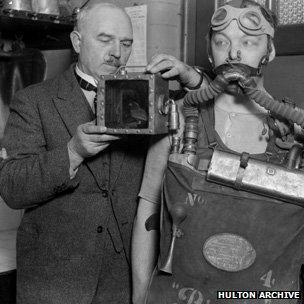

Prof Haldane down a mine in about 1910

"After the ear-splitting blast came the silence, despair and heartache in the early morning rain," said Prof Goodman.

"Rumours spread like wildfire throughout the valley communities that a terrible disaster had occurred at Tylorstown."

David Owen, archivist and author on the Rhondda coalfield, said: "Wild claims were made which put the numbers of men trapped or buried as high as 700, and one early newspaper report did little to calm the fears of the close-knit community.

"Although the explosion occurred in No 8 Pit, the worst consequences were experienced at No 7 Pit. The force of the explosion brought down heavy falls of roof and sides, cutting off all expectation of life and making recovery of the casualties a very time consuming operation."

It was against this backdrop that Prof Haldane arrived in Tylorstown, and immediately insisted on going underground to see the victims before they were moved, no matter the danger.

He was perplexed to discover four men dead in a chamber, with a lit oil lamp still burning between them.

This was significant because flames require at least an 18% concentration of atmospheric oxygen to burn, whereas humans can survive with as little as 10%.

The explosion happened in the Tylorstown No 8 pit

As Prof Goodman explains, this meant Prof Haldane recognised immediately that his theory of suffocation was entirely wrong.

"Prof Haldane wasn't interested in finding proof for his theories and he wasn't afraid of admitting he was wrong if it helped him get to the truth," he said.

"It clearly wasn't the blast which had killed the miners - there wasn't a mark on them. So if it wasn't the absence of oxygen, then he concluded that it must be the presence of something else.

"He and a local doctor conducted post mortems on the victims - not a common procedure at the time - and finally came up with an answer to why they all looked so rosy and healthy."

Life and death

In fact what Prof Haldane had discovered was that the pink tinge which had been traditionally explained away as bruising or burns, was in fact haemoglobin in the blood binding with carbon monoxide rather than oxygen.

In effect the men had suffocated, though not through a lack of oxygen.

His next few months would be spent locked in a gas-filled laboratory, testing the effects of carbon monoxide on himself and a series of smaller animals.

His children were told to watch through the windows, with orders only to open the doors if either Prof Haldane or one of the animals collapsed.

He concluded that whilst both mice and canaries were 20 times more susceptible to the gas than humans, canaries would give miners the best advance warning, as they stopped singing and would fall off their perch.

It started a 100-year tradition of miners treating their canaries like pets, talking and whistling to them, as their songs may one day prove the difference between life and death.

But canaries weren't the only life-saving finding in Prof Haldane's Tylorstown report.

A scientist with a canary and testing breathing equipment

"He discovered that whilst the natural reaction was to run away from explosions, the best chance of survival came from staying as low as possible, and crawling very slowly so that the heart and breathing rate stay very steady," said Prof Goodman.

And the miners were not the only ones to benefit from Prof Haldane's findings.

Whilst many thought the use of canaries in mines to be cruel, mistakenly believing that the bird had to die in order to provide an early warning, Prof Haldane was extremely concerned for the welfare of the animals on whom he experimented.

"In some ways you could say that he was one of the first anti-vivisectionists, as he would rarely, if ever, do something to an animal which he wasn't prepared to do to himself," said Prof Goodman.

"Probably the ones who suffered the most in his experiments were his children. His daughter Naomi Mitchison, who became a very successful novelist, wrote of how her friends ran away when she told them that her father had invited them all for tea because he wanted their blood!"

- Published15 January 2012

- Published18 September 2011

- Published14 October 2010