Orphan Lê Thanh still fighting effects of Vietnam War

- Published

This photo of Lê Thanh (far left) on a plane with other orphans as they are airlifted out of Vietnam was on the front page of the Daily Mail in 1975

Lê Thanh was one of 99 orphans airlifted to Britain at the end of the Vietnam War to be adopted. Now, 37 years on, he is trying to raise awareness of the plight of those still dealing with the effects of the conflict.

Lê Thanh is 40 this year. At least, he thinks he is.

His birthday was given to him by a Rhondda dentist after the Welsh family who adopted him at the end of the Vietnam War tried to establish his age through dental testing.

He doesn't know anything about his background - he was just told that when he was taken to an orphanage, he was well nourished, suggesting his family had cared for him before they were possibly killed.

Even his full Vietnamese name Lê Thanh Hung was lost in the confusion of his adoption. He now just goes by the complete name Lê Thanh, without a surname.

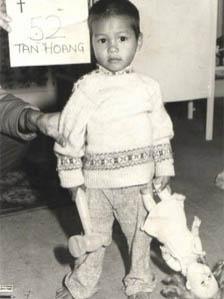

The only picture Lê Thanh has of his time at an orphanage in Vietnam

Apart from these few details and a photo of him clutching a doll at his orphanage, very little of his life as a toddler is known.

But that changed in 1975 when Lê Thanh was one of 99 orphans put on a Boeing 747 chartered by the Daily Mail newspaper.

It was destined for Britain and families who were keen to adopt the children, who had been at orphanages in what was then called Saigon - now Ho Chi Minh City - where fears were high as the Viet Cong advanced at the end of the war.

A photo of him and two other orphans asleep on the plane was on the front page of the newspaper, with the mercy mission dubbed 'Operation Babylift'.

It should have been the start of a happy ending for three-year-old Lê Thanh, but he said life had not been easy in Wales and that he did not feel that he belonged anywhere.

He says it has driven him to find out more about the country where he is from and raise awareness about the problems it still faces as a result of the war between North Vietnam and its communist allies, and the government of South Vietnam, supported by the United States and other anti-communist nations.

School bully

"Growing up in the Rhondda in the 1970s was obviously very difficult as there were no other Oriental people growing up in that area at that time," said Lê Thanh, who was adopted by a vicar and a health visitor from Penygraig and was brought up with their two other children.

"I was bullied by the school bully but I stood my ground. My philosophy is what doesn't kill you makes you stronger.

"But I didn't really have a happy childhood. It wasn't impoverished but I have always been different and I never really fitted in. Even in today's society I still don't really fit in."

Lê Thanh went on to become a software engineer and lives with his wife Rufaro, who is English but grew up in Zimbabwe and Ethiopia, and their two daughters, Nyasha, 11, and eight-year-old Liêu, in Pontypridd.

However, a lingering feeling of "not belonging" led him to try to reunite the 99 Daily Mail orphans.

He was spurred on after Viktoria Cowley, who was one of the children pictured with Lê Thanh on the Daily Mail front page, traced him and got in touch a few years ago.

"I now co-ordinate reunions of fellow adoptees and although I mark it as a social reunion, the true reason behind it for a lot of people like myself, with my background, is that they're very much displaced," he said.

"They are still very much uncomfortable in their own skins and have their issues.

"Lots of people who went through this [being adopted] thought they were the only ones. The reunions let us connect and share experiences and feelings."

Going back

Lê Thanh joined with some of the adoptees to go back to Vietnam in 2010, which the Vietnam Volunteer Network helped to organise, taking his family with him.

But he always regretted the fact he did not have time to volunteer at some of the country's orphanages, like his fellow travellers, and pledged to go back.

Lê Thanh and his friends volunteered at orphanages across Vietnam during his trip at the end of 2011

He did so at the end of 2011, accompanied by friends and colleagues from Creditsafe in Cardiff Bay, including Rebecca McGrane and Matt Carter, who helped him set up the Reaching Out project to raise money for people still affected by the war in Vietnam.

He said he was shocked to see how much suffering and hardship is still there, caused by a war nearly 40 years ago.

"We went to orphanages and peace villages, which are basically hospitals, and saw children with limbs missing and other disabilities, which we were told were as a result of chemicals used in the war," he said.

"It really affected me, particularly in one of the orphanages in Saigon where we worked for five days.

"On one ward there were three or four rooms and in each one there were about 20 to 40 children in cots in each room, from toddlers to children of 14 and 15.

"But there were only about three to four carers in each room. These children end up spending most of the day in their cots staring out.

"These orphanages don't have enough staff to be able to fully look after the children and this is where volunteers are needed."

Raising awareness

He said he and his colleagues initially set up Reaching Out to raise money for aid for their trip, but Lê Thanh said he will now keep it running to raise awareness about how people can help those in need in Vietnam.

"I am going around schools and community groups to talk about my experiences and I'm keen to show people how volunteering can make a real difference," he said.

"Also, things like funding prosthetics and buying a cow for farmers can help. One farmer had had his arms blown off by a landmine from the war so he couldn't work. These were all issues I was oblivious to until my recent trip."

He said he would continue to travel to Vietnam, as well as staying in touch with fellow adoptees, in a bid to help himself and others.

"Every time I come back from Vietnam I always promise I will go back," he said.

Lê Thanh went to Vietnam with his wife and daughters and visited the site of his old orphanage

"You want to feel at home. The problem is I don't really have an identity in the UK, even though I'm British and have lived in the UK all my life.

"But you go back to Vietnam and you don't really fit in there either. Every time I go there, Vietnamese people see people like us [adoptees] and say "same, same, but different", meaning we look the same as them but talk different.

"It makes you feel a little awkward.

"But going out to Vietnam in December to deliver our aid to the orphanages helped me as I found I have a strong desire to strive to help other Vietnamese people who are still affected by the war.

"Something struck a chord with me. I suppose I was fortunate to have a comfortable upbringing, even though that was difficult. Now I want to do something for those less fortunate."