World War I cartoonist JM Staniforth's work to be digitised

- Published

JM Staniforth's establishment views came into their own during WWI

Ask most people in Wales to name a famous cartoonist, and the odds are that an overwhelming majority would say Gren.

But what many aren't aware of is that over half a century before the late South Wales Echo cartoonist was even born, another satirical artist had been blazing the trail in which he would follow.

From 1890, JM Staniforth founded the tradition of using cartoons to pass social commentary on Welsh life, helping to establish the Western Mail as the dynamic and modernising face of journalism in Wales.

Amongst his peers he was regarded as one of the finest at his art, though thanks to his traditional, "establishment" politics, nowadays his work is largely overshadowed by that of more liberal and radical commentators.

But that is something Prof Chris Williams of Swansea University is hoping to put right, with the help of a grant of £70,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund to digitise around 1,300 examples of his work during the World War I.

He said: "Throughout his life, JM Staniforth created over 15,000 cartoons, but perhaps the most typical, and influential were those he drew during World War One."

"As the Western Mail had been founded and patronised by coal barons, Staniforth's establishment, right-wing outlook was very much on-message with the paper as a whole at the time. This meant that he was viewed with some scepticism by the burgeoning Labour movement and the unions.

"But on the outbreak of war in 1914, his traditional and patriotic style came into its own, and he became a household favourite."

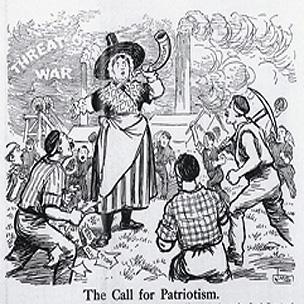

Dame Wales, or Ma Cymru, was a favourite figure of Staniforth

His stock character was Dame Wales or Ma Cymru, a middle-aged woman in traditional Welsh costume who dispensed home truths in a Valleys vernacular to lords and striking miners alike.

Though perhaps Joseph Morewood Staniforth wasn't the archetypal character to be toeing the establishment line, and arguably he was an even less likely Welsh patriot.

Because he was in fact born in Gloucester in 1863, the son of a cutler and tool repairer.

The family moved to Cardiff in the 1870s, where his father opened a shop on Caroline Street.

Staniforth himself left school at 15 without any formal qualifications, and became an apprentice lithographer with the Western Mail.

His artistic talent and innate wit were spotted by the paper's founding editor Henry Lascelles Carr, who gave him his own daily slot.

But while his work may appear safe by modern standards, Prof Williams argues that it was in fact questioning for its day.

"In some ways Staniforth was a great defender of the status quo, though there are numerous examples in his work of his affinity with the ordinary worker, and in particular the ordinary soldier on the Western front.

"In order to get a sense of his true feelings, you need to look at what he "wasn't" saying as much as what he 'was".

"He reflected society back to his audience in terms they'd identify with, and as such they're a little window on the culture at the time. If he is illustrating the prime minister as a music hall artist, he is making assumptions about what the audience can understand.

"There are a lot of raw materials for social historians in the presumed knowledge of the time, and his World War One work in particular is revealing of how attitudes changed through the course of the conflict."

Perhaps the greatest testament to his work was the way in which he drew a constant mailbag of complaints throughout his three decades on the Western Mail, yet was still voted the most popular feature by readers during the paper's 50th anniversary celebrations in 1919.

Prof Chris Williams said the project would help explain the cartoons

'British art of caricature'

After his death in 1921, Llewellyn Williams, the Recorder of Cardiff, wrote in the Western Mail: "The death of Staniforth is not merely a loss to Wales, but to the British art of caricature.

"Staniforth made fun of Wales and Welsh life and Welsh men. His satire was always good natured, but it was always true.

"Welsh journalism is greatly the poorer by his loss."

The Heritage Lottery Fund grant will go towards training 30 volunteers and 80 under-graduate students at Swansea, in how to care for the original drawings, as well as digital scanning and clean-up techniques.

The project's website will be live in time for the centenary of the outbreak of World War I next September.

- Published21 March 2013

- Published19 September 2010