Pioneering Swansea professor's World War II work remembered

- Published

As a result of Prof Bowen's work the Royal Navy and RAF were able to break the Germans navy's stranglehold over the north Atlantic

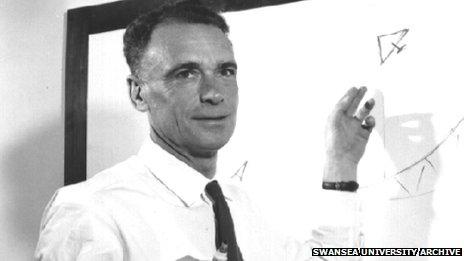

Before World War II Edward George Bowen was a shy, slightly anonymous professor of physics at Swansea University.

But 70 years ago this month, this son of a Cockett sheet metal worker would go on to change the course of our everyday lives.

Because Prof 'Taffy' Bowen managed to miniaturise radar, from a nationwide network of 50ft (15m) tall masts in 1935, right down to something which by 1943 could be fitted into the noses of planes during the Battle of the Atlantic.

This meant that while Allied fighters could detect German U-Boats from a range of up to 100 miles (160km) - even though they were thousands of miles away from the nearest land-based radar systems - the U-boats were unaware of their presence until the planes were virtually on top of them.

As a result the Royal Navy and RAF were able to break the Nazi stranglehold over the north Atlantic, allowing vital arms and food to reach Britain from America and scuppering Hitler's plan to starve the UK out of the war.

If that wasn't enough, the breakthroughs which Prof Bowen made in the field of electro-magnetism during his career led directly and indirectly to a string of other developments:

Modern air-traffic control systems

Cathode ray tube television sets

Microwave ovens

Insulated electrical cable

Rain-making

The radio telescope which received the first images of the Moon landing in 1969

Mike Charlton, who now holds the seat once filled by Prof Bowen as professor of physics at Swansea University, says his predecessor was one of the most brilliant minds ever to come out of Wales.

"Taffy was born in May 1911 to a quite unremarkable working-class family in Swansea, but from a very early age it was obvious that he was different," said Prof Charlton.

"By 1920 he'd already built his own valve radio transmitter. A marvellous achievement for any nine or 10-year-old boy, but this was fully two years before even the BBC made their first broadcast.

"He joined Swansea University aged 16, he had his MSc (master of science degree) by 19, and was a professor aged 24."

Enemy aircraft

In 1935 Prof Bowen's brilliance brought him to the attention of the inventor of radar, Scottish scientist Robert Watson-Watt.

Radar helped Allied aircraft find German U-boats long before the submarines realised they had been detected

He was set to work on a top-secret spin-off project from radar, investigating whether high energy electro-magnetic waves could ever be used as a "death ray" in order to bring down enemy aircraft.

Prof Bowen soon discovered that the power required to create such a death ray made the notion impractical, but as Prof Charlton explains, he did learn that using shorter frequency microwaves vastly improved the efficiency of Watson-Watt's principal of radar.

"Radio travels in metres-long, loopy waves," added Prof Charlton.

"Their arc through the air is so vast that one of them could quite easily miss something even the size of an aeroplane, meaning that to be effective radar had to have enormous chains of transmitters throughout the country.

"But what Taffy discovered was that microwaves, with their shorter frequency and higher energy, bombard something the size of a plane with many times more waves, and send back a much clearer image for the energy expelled.

"Put simply, if someone throws a bucket of water out of the window, it's comparatively easy to get out of the way. But you try dodging the rain."

Moon landing

And even though Prof Bowen's death ray never came to pass, its principle lives on to this day in most kitchens, in the form of the microwave oven, as does his research into cathode ray tubes, which influenced the design of televisions until the advent of the flat-screen TV.

After the war he switched old south Wales for New South Wales in Australia, where he built the Parkes radio telescope which received the first slow-scan images of the Moon landing in July 1969.

Prof Bowen died in Sydney in 1991, aged 80.

According to Prof Charlton, he is perhaps best summed-up by the wackiest of his experiments.

"Taffy was an avid cricketer and sailor, both highly weather-dependent pastimes," he said.

"So when he heard about American efforts to produce and control rainfall through cloud seeding, he enthusiastically embraced the idea and dramatically improved its effectiveness.

"That alone probably shows why Taffy was so successful. Not only was he a brilliant scientist, he had the imagination to anticipate how what he was working on could benefit the real world."

- Published25 May 2013

- Published12 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013