World War One: How Swansea helped refugees from Belgium

- Published

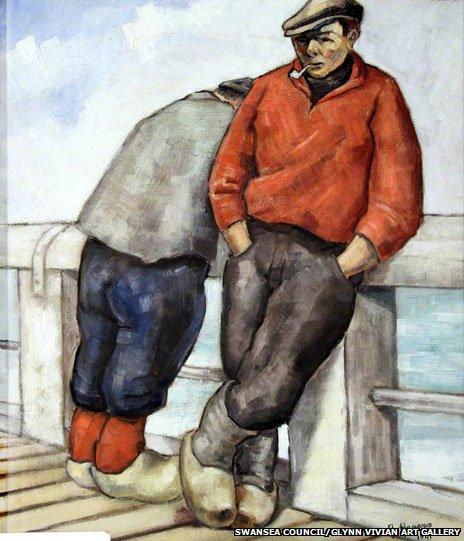

The painting was given as a "token of gratitude" by the Belgian government

When Swansea's copper industry was spawned more than 200 years ago, few could have predicted the positive effect it would have for people fleeing the battles of World War One as they spread across Europe.

The city was famed for its copper production and in the 19th Century, Swansea was known as "Copperopolis".

It was a thriving industry and by the 1840s Swansea produced over half of the world's finished copper.

The recruitment of skilled workers from Belgium who had a method of smelting zinc which was considered the best had led to a sizeable population living in the city.

And it was this community, embraced by the local population, which led to the acceptance of World War One refugees from Belgium in a way that was largely absent in other UK towns and cities.

Around a quarter of a million Belgian refugees fled to Britain upon the German invasion of their homeland in 1914 with at least 5,000 finding themselves in Wales.

Despite initially receiving a warm welcome everywhere they arrived, many discovered that the hospitality of their British hosts soon dried up.

But this was not the experience of the 762 who came to Swansea.

University of East Anglia historian Dr John Alban first became fascinated by their story in the 1970s, when as part of his role as Swansea's city archivist, he unearthed the records of the Swansea War Refugee Committee.

He explained: "The Belgian story in Swansea goes back much further than World War One, right to the 1840s, when Swansea copper masters were desperate to discover the most efficient and cheapest means of smelting zinc, which was locally known as spelter.

"The Belgian method proved the best, and from the mid-19th Century the hunt was on to recruit skilled speltermen from Belgium so that by the beginning of the 20th Century there was already a sizeable Belgian community in Swansea."

Dr Alban argues that whilst these first speltermen and their families seem to have assimilated well into Swansea life, they nevertheless maintained strong links with home, providing a "pull-factor" for WW1 refugees which was largely absent elsewhere in the UK.

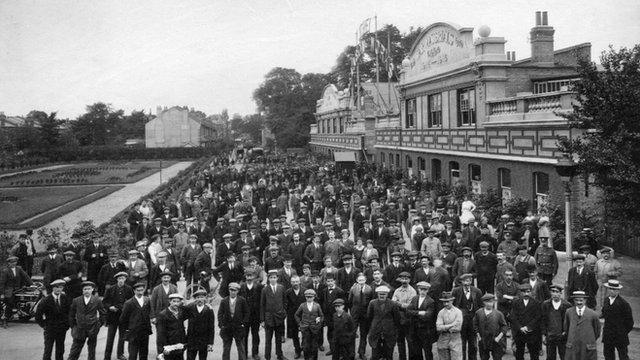

These Belgian refugees were at a workhouse in London in 1914

He said the first groups of Belgian refugees started arriving in Swansea in early September 1914, "even before the official relief effort had begun".

"Almost certainly these were people who had ties with Swansea's existing Belgian community, so they seem to have had ready-made intermediaries to help them adjust to the language and culture," said Dr Alban.

"Later on in 1915 and 1916 that direct link seems to have been broken as many more refugees arrived, some via the Netherlands, but by then around Swansea there was already a positive perception of the Belgian immigrants."

'Very adaptable'

Yet the Swansea Belgians are among the most anonymous in Wales.

But thanks to the efforts of art-collecting Llandinam sisters Gwendoline and Margaret Davies, many notable writers, artists and musicians from Belgium were found new homes in mid Wales.

Indeed, across Wales considerable effort seemed to have been put into catering for what the then journalist Flora, Lady Lugard once coined as "The better class of Belgian".

In contrast, as economic difficulties and food shortages began to bite, local newspapers frequently labelled working-class refugees as free-loaders and troublemakers.

However, these are slurs which Dr Alban contends are conspicuous by their relative absence in Swansea.

He said: "Whilst there are frequent accusations of idleness and disorder amongst Belgians in the newspapers of other towns, aside from the occasional story of drunkenness, there's virtually nothing of that nature recorded in Swansea.

"In fact, the Swansea Belgian Refugees Committee's report of September 1916 makes mention that of all the refugees in Swansea, only six still hadn't found work.

"Moreover, the Belgians who came to Swansea proved very adaptable: for example, a high court judge and six Antwerp diamond-cutters, who couldn't pursue their original professions in Swansea, found alternative employment as workers in the local spelterworks.

"So there doesn't appear to have been the 'better class of Belgian' class differences which were apparent elsewhere."

And as a thank you to the people of Swansea, a painting of "Two Fishermen of Ostend" by Belgian artist Albert Hagers hangs in the city's Glynn Vivian Art Gallery.

An accompanying inscription reads: "A small token of the gratitude of the Belgian government to Swansea for all the kindness shown to the Belgian people who have come to the town over the years."

- Published21 March 2014

- Published24 February 2014