Wales NHS: Call to 'respect Bevan's values'

- Published

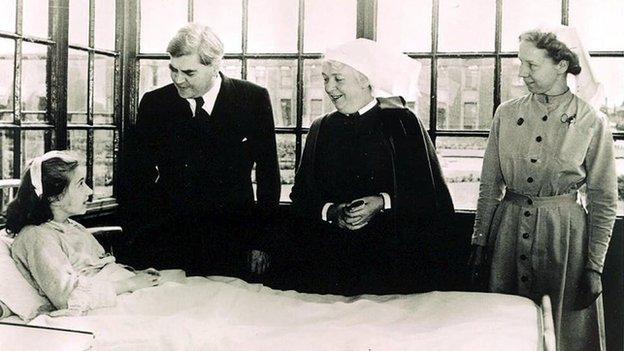

As Labour health secretary in 1948, Aneurin Bevan meets the first patient of the NHS in Trafford

Aneurin Bevan's first major personal experience of the National Health Service he created in 1948 came over eleven years later. He was admitted to the Royal Free Hospital on Gray's Inn Road, in London, on 27 December 1959, for what he thought was an operation on a stomach ulcer. He was to remain there for seven weeks, and, though he never knew it himself, he was suffering from terminal stomach cancer which killed him only months later, on 6 July 1960.

During these months of convalescence, spent with his wife Jennie Lee at their farm in Buckinghamshire, Bevan gave his final newspaper interview, which appeared in the Guardian on 29 March 1960. He was asked how he had been passing the time, and said he had been "reading newspapers avidly" since they were his "one form of continuous fiction". No doubt Bevan would have had a wry smile on his face this week as the Welsh government responded to the Daily Mail's latest attack on the Welsh NHS.

Neither would he have been surprised that those attacks were mirrored on the Conservative benches of the House of Commons. During one debate in 1949, as one Tory MP after another made speeches complaining about the NHS, Bevan taunted them for their negativity, using a word from Thomas Gray's poem Elegy written in a country churchyard - "The Tory party used to represent itself as a jocund party." I doubt Nye would have held back in responding to the critics of the health service in 2014 any more than he did in 1949.

Bevan's vision of the National Health Service was of comprehensive provision based on patient need, not wealth. He had wanted to replace the patchwork system that existed in the pre-war era with a truly national service. To achieve this, one of his key decisions was to nationalise the hospitals themselves, with the only separate class of hospital to be for teaching.

Bevan did not want a health service structure vulnerable to fragmentation, and he would no doubt have strongly disapproved of the UK government's changes to the English NHS. Section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012, which, with its procurement and competition regulations, ushers in marketisation, flies in the face of Bevan's conception of the NHS.

In the days before the NHS's official launch, every British household received a letter containing a defining phrase that summed up its impact: "It will relieve your money worries in time of illness." This was much more than a political triumph. Bevan brought about a cultural shift in attitudes to healthcare in the UK. Health care free at the point of delivery was now a right, an expectation, not a luxury.

It was entirely fitting that, in Danny Boyle's London 2012 Olympics opening ceremony, the NHS was lauded as a great national achievement. Bevan may not be around to fight for his creation any longer, but the values that drove the creation of his NHS are something that modern politicians would be well-advised to respect.

Nick Thomas-Symonds is the author of Nye: The Political Life of Aneurin Bevan

- Published26 October 2014

- Published26 October 2014

- Published26 October 2014

- Published26 October 2014

- Published25 October 2014

- Published23 October 2014

- Published22 October 2014

- Published21 October 2014

- Published21 October 2014

- Published14 October 2014