Welsh war artists' crucial role in documenting war

- Published

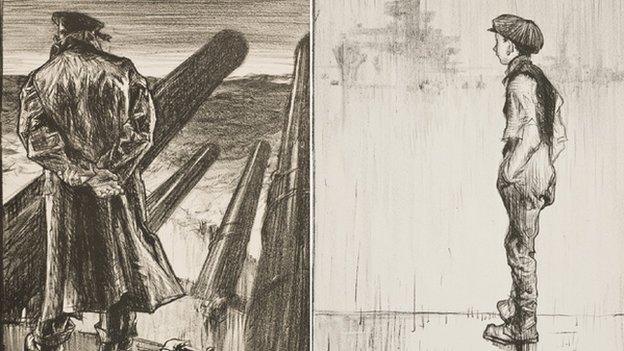

Welsh artist Frank Brangwyn documented the First World War in his sketches

During this centenary year you will have seen many images of the First World War.

But as well as the use of films and photographs to document what happened, the new role of the "official" war artist also provided an alternative interpretation of the conflict.

Welsh artists Frank Brangwyn and Augustus John were among those who documented life on the front line, and it is a tradition that survives today.

Alongside the men who fought and died in the First World War, the official war artist was a new breed of observer.

While battles have been documented by British artists in tapestry and oils from 1066 to Trafalgar, the new conflict created a government sanctioned pool of artists.

Wrestling with war

The artists often found themselves wrestling with the war, and trying to make sense of it. Some of them had served in the trenches, others never left Britain.

But many were hired by the government to produce posters and prints that were designed to stir up support for the war.

Some of those are currently on display at National Museum Cardiff.

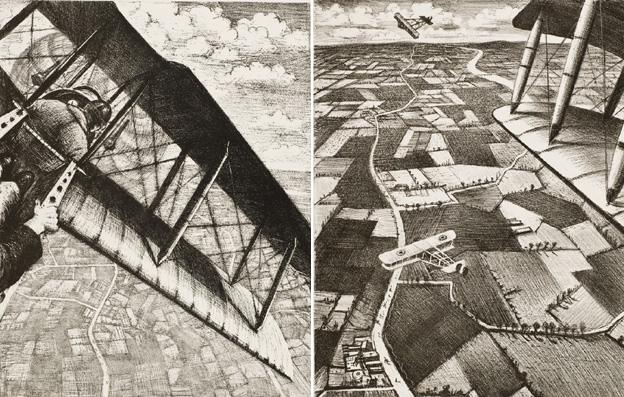

World War One artwork by Christopher R. Nevison

The collection of prints from 1917 is divided into "efforts" and "ideals".

The efforts show the shipbuilders, women welders, and aircraft pilots, while the more abstract ideals use allegories to convey the perils of war, and the hope of victory.

The images were not designed to be traditional propaganda posters, but more high-end works of art whose sales could generate an income for the government.

There are several Welsh artists among those who were commissioned for the series.

'The Dawn' by war artist Augstus John

Augustus John's allegorical painting "The Dawn" provides the optimism of sunshine after death's grip has been loosened, while Frank Brangwyn's fascination with the sea prompted his lithographs detailing the sailors at work.

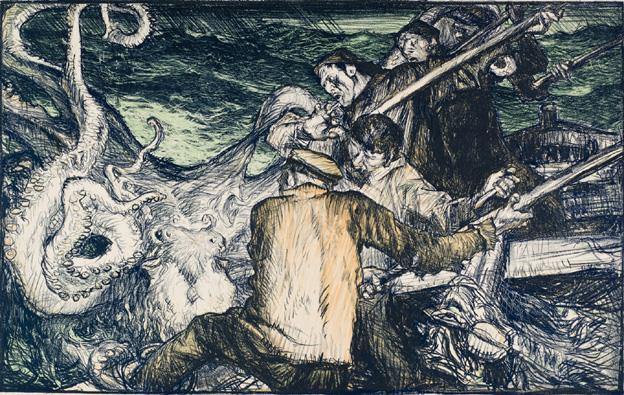

His own allegorical work, "The Freedom of the Seas", shows a small boat being besieged by a giant tentacled creature, which the exhibition's curator Beth McIntyre, said was representative of "the German U-boats and their creation, and what was happening on the seas".

'The Freedom of the Seas' by Frank Brangwyn

The collection of prints was distributed to galleries around the world, and displayed the work of some of the country's finest artists.

"Muirhead Bone, one of the artists represented in the show, was actually the first official war artist in Britain," said Ms McIntyre.

"It was very important for them - some went on to be made official war artists, people like Eric Kennington and CRW Nevinson, which meant they didn't go back to fight.

"This gave them the opportunity to use their skills, but also their experience - as they'd both been at the Western Front already. Some artists' reputation rocketed during the war because of the work they were producing."

Modern conflicts

Maesteg-born Christopher Williams' striking painting "The Welsh at Mametz Wood", where so many soldiers died, is currently on display at the Royal Welch Fusiliers Regimental Museum at Caernarfon Castle.

It will undergo some restoration work by National Museum Wales next year before being included in an anniversary exhibition to mark the centenary of the battle in 2016.

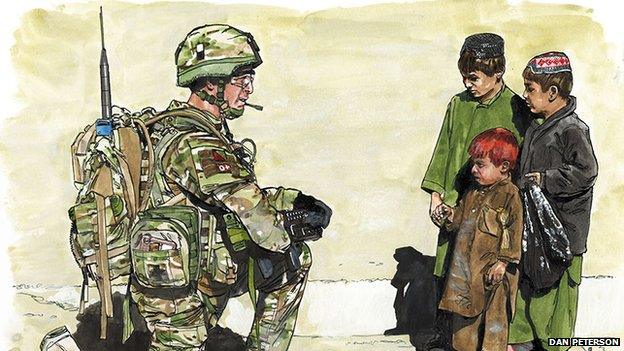

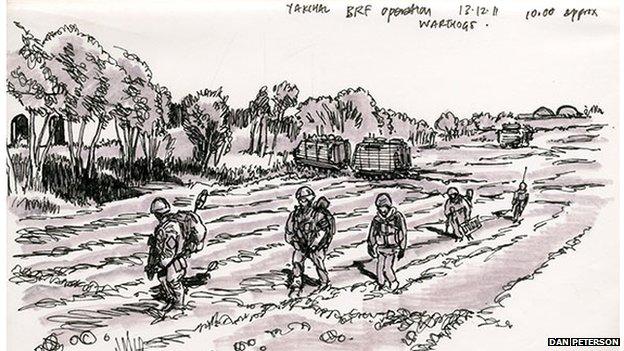

In modern conflicts, too, the official war artist has a place alongside the armed forces. Dan Peterson from Cardiff is among the current pool of to have travelled to conflict zones.

He spent a month in Afghanistan with the Queen's Dragoon Guards, known as the Welsh Cavalry, in November 2011.

From roadside sketch to full oil paintings, his workload mirrors that of the official war artists of a century ago.

Dan Peterson is one of the more recent artists to document life in a war zone

"When I first went out, they weren't sure, they had to get used to me and who I was, and how I fitted in," he said.

"But within a week I was out patrolling on foot, and within a couple of weeks I was out on operations with bullets flying, and explosions. Right in the thick of it."

"They said to me: 'You must be mad, sir, carrying a pencil and not carrying a weapon.' But I said that's what you're here for - so I can look, and you can look after me."

He has produced a number of prints, acrylic and oil paintings, while his work has also been published in a book commemorating the Welsh Cavalry's tours of Afghanistan.

Dan Peterson's artwork ranges from prints, to acrylic and oil paintings, to sketches

The times of relaxation following a patrol often afforded him the time to sketch the soldiers he was travelling with.

"Those are the moments that count, it's that time for a few minutes or half an hour after the frenzied action takes place, in which they can contemplate what's just occurred."

The role of the official war artists has changed little in a hundred years.

But alongside the TV crews and the camera phones, the sketchbook remains a crucial record of life on the frontline.

- Published9 November 2014

- Published7 November 2014

- Published9 November 2014