Patients given kidneys rejected 'unfit' by other hospitals

- Published

Robert Stuart and Darren Hughes received organs from a donor infected with meningitis-causing parasitic worms

Two transplant patients died after receiving kidneys which had been rejected as "unfit" by other hospitals, an inquest has heard.

Robert Stuart, 67, from Cardiff, and Darren Hughes, 42, of Bridgend, were given organs from a donor infected with meningitis-causing parasitic worms.

Doctors knew the alcoholic donor of the kidneys had died from meningitis, Cardiff Coroner's Court heard.

The transplants took place at Cardiff's University Hospital of Wales last year.

Post mortem examinations revealed both men had the deadly parasitic worm halicephalobus in their bodies after the transplant.

The court heard the donor was an alcoholic who was admitted to an unnamed hospital on 21 November where it was found he was suffering from meningitis and septicaemia.

No bacteria were found after a lumbar puncture but he died on 29 November, with cause of death given as meningoencephalitis, a form of meningitis.

The parasitic worms were found in several of Mr Hughes's organs

Pathologist's findings

The coroner heard there have only been five known cases like this worldwide in humans - all of which had proved fatal.

Pathologist Fouad Alchami said the primary cause of death for both men was meningoencephalitis, a form of meningitis, caused by the presence of the worms.

This was the first known case of human-to-human infection and the first case in the UK, the inquest heard.

He said the men had a "heavy infestation" of nematode worms in their brains.

Dawn Chapman, a specialist transplant nurse at UHW, told the inquest that five transplant centres had declined the donor's kidneys before they were offered to them under a fast-track scheme which happens when five or more centres reject an organ, or it has been out of the body for more than six hours.

Mr Hughes's family said it was not told the kidney could be infected before the transplant, and they were only informed of the condition of the donor a month after Mr Hughes died in December 2013 - two weeks after his transplant.

He said the family were under the impression that the donor had been killed in a car crash and they had no idea of his health.

Mr Hughes said he would not have signed the consent form for his disabled son had he known the organ came from an alcoholic.

He added they were informed the donor's organs had been rejected by several other hospitals after being deemed "unfit for transplant".

Ian Hughes said his family were unaware of the risks involved

Representatives for UHW suggested to Mr Hughes at the inquest that the surgeon had told them prior to the transplant the donor had a brain infection which was low risk. He denied this.

Mr Stuart's widow Judith said her husband would have also refused the transplant had he known of the brain infection suffered by the donor.

On 30 November, Mr Stuart was called to the hospital and was told a kidney was available.

Both transplants took place at the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff

Mrs Stuart said she stayed with her husband until he went into theatre and at no point was he told in her presence about the nature of the kidney or informed about the donor.

Under cross-examination from Cardiff and Vale University Health Board representative George Hugh-Jones, Mrs Stuart rejected a suggestion she had missed a conversation between her husband and the surgeon about the nature of the donated kidney before he went into theatre.

He was discharged on 6 December but re-admitted on 10 December when he became unwell.

Mr Stuart was put into an induced coma and died on 17 December after life support was withdrawn.

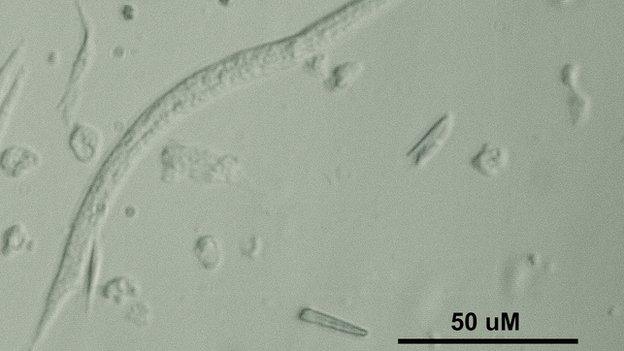

The donated kidneys were infected with a parasitic worm

Halicephalobus parasite

The parasitic worm halicephalobus lives in soil, manure and compost

It infects animals and humans, but this is still incredibly rare

There have been only a handful of cases in humans since the infection was first described in 1954 by a researcher called Stefanski

It is unclear how the worm gets into the body - it could be by ingestion of its eggs or it entering through a break in the skin

Once inside, it can multiply and invade tissues such as the brain and kidneys

Doctors diagnose it by looking at tissue samples, but since it is so rare it is not something that will be top of their check list

The problem may only become apparent after a post mortem examination

- Published14 November 2014

- Published14 November 2014

- Published17 November 2014