The challenge of change in the NHS in Wales

- Published

It can't have escaped many people's notice that English politicians continue to throw a spotlight on the performance of the Welsh NHS. With Wales the only UK administration controlled by Labour, the Conservative party has consistently sought to highlight the state of the Welsh NHS, perhaps in response to Labour's comparative political advantage on the NHS, external in the forthcoming UK election.

For its part, the Labour party - both in Cardiff and Westminster - has repeatedly defended its record by claiming it is difficult to compare the NHS in England with its counterpart in Wales.

Comparisons are difficult but some can be made. Last year the Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation published a study, external taking the long view of NHS performance across the four countries using around 20 comparable indicators of performance, from patient satisfaction to ambulance response times.

The overall conclusion was that performance across all four countries had improved at more or less similar rates over the 2000s as a result of the huge boost in funding when government investment in the NHS doubled in cash terms in all countries.

No one country consistently lagged behind or outperformed another, once relative starting points were taken into account. A foreigner would be much more struck by the similarities than the differences.

The differences

Comparing Wales with an English region is likely to be fairer

However, England and Wales differ in many ways as countries, and since 1999 their two health services have been separately run. So it shouldn't be very surprising that there are some important differences. They flow from four factors:

The structure and management of the service

Wales doesn't have the "purchaser-provider split" - the internal market where parts of the English NHS buy services from other parts. Instead the Welsh NHS operates through integrated health boards. Unlike England, it makes very little use if any of the private sector. However, our conclusion in the Four Countries report was that much as this kind of structure is debated and focused on by analysts and politicians, it has very little impact on relative performance. Of much greater importance are:

Population differences

The Welsh population is older, sicker and has more deprivation than the population of England. All these factors affect people's health and therefore mean greater demands on the Welsh health service. Any comparisons need to take this into account. There is also an inherent unfairness in comparing performance for a population of three million with that for one of 54 million, external.

So comparing Wales with an English region is likely to be fairer, although not straightforward, which is why we used the North East of England as a comparator in our report where possible. Its population characteristics are much closer to those of the devolved countries than England as a whole.

Policy priorities

The devolved government in Wales has used its powers to set different priorities and a different tone from its London counterpart. It has emphasised prevention and public health more than England. Meanwhile, it came later to introducing goals on waiting times, and over the last decade it did not adopt the emphasis of the English NHS on enforcing these through "targets and terror", as the English performance management regime has become known. , external

Investment decisions

Difficult decisions have been required since 2010 and the start of austerity.

Different approaches have been adopted. England (and Scotland) have protected NHS spending which has seen some small real terms growth over the last four years. Not so in Wales, where health spending has been cut in real terms , externalby 4.3% between 2009/10 and 2012/13, although there have now been further cash injections in 2014/15 and planned for 2015/16 to reverse this trend.

On the other hand, England has cut government grants to local authorities, resulting in a 16% reduction in funding for social care for the over 65s, external - a cause of some anxiety. In Wales, local authority spending has held up, although this is now planned to change. Wales has chosen to prioritise its spending differently within the health sector, adopting policies like free prescriptions and car parking.

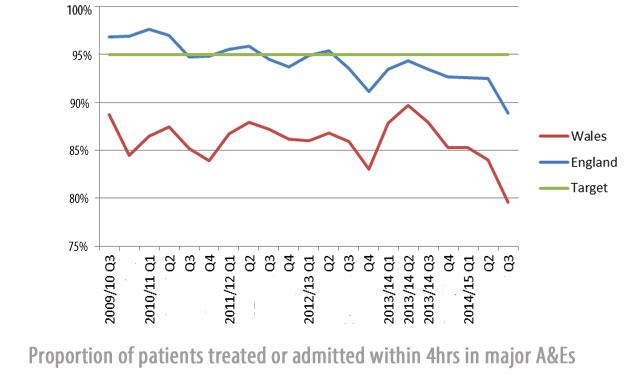

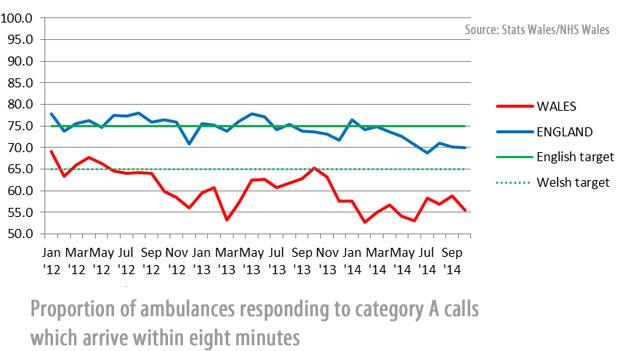

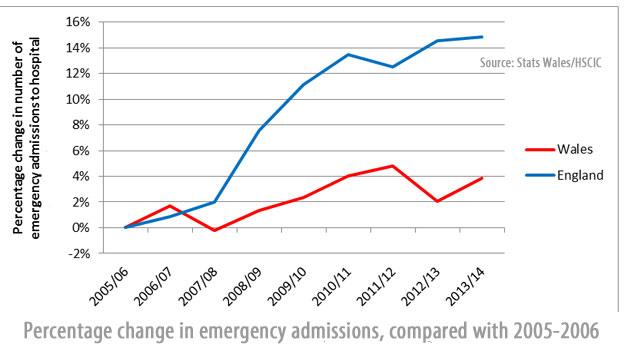

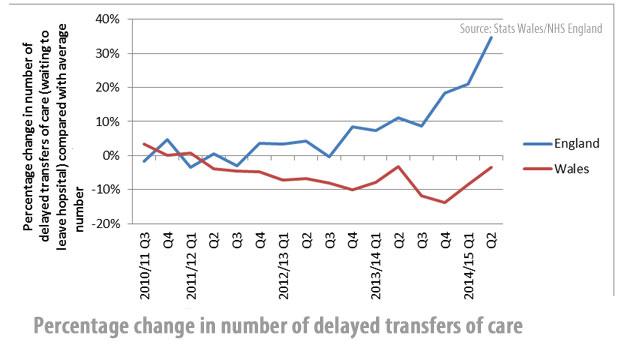

The collective impact of different populations, policy choices and investment decisions on recent performance can be seen in the following graphs.

Since 2010, Welsh performance on waiting times for planned hospital admissions, A&E, and ambulance response times has deteriorated significantly, more so than in England, although A&E performance and ambulance response times have been falling there too.

The picture for waiting times for diagnostic services is similar. But looking at cancer services waiting times, while performance has dipped slightly in both countries, in absolute terms Wales remains marginally ahead of England, despite missing its (higher) target.

The experience of the two countries on the numbers of people being admitted to hospital in an emergency and delays in discharging people from hospital into social or community care has been notably different. England has seen very rapid growth in emergency admissions and more recently in delayed transfers of care. Both of these are causes for concern: they suggest out-of-hospital services are struggling to deal with and receive patients before and after they need inpatient care.

Nuffield Trust chief executive Nigel Edwards spoke to a woman whose 92-year-old mother waited hours for an ambulance

The rising trends are to some extent likely to reflect cuts in social care spending, as well as growing demand from rising numbers of elderly people. Wales has also seen growth in emergency admissions, but on nothing like the same scale, and delays in discharging people from hospital seem to have changed little in recent years. This may reflect the different policy approaches and investment decisions made.

One possible partial explanation for the difference between the two countries is that the more rigorous application of the four hour A&E target in England has led to a rise in short stay admissions to help hospitals hit 95%.

This is not necessarily good news for patients if they then simply wait somewhere else or even get stuck in hospital when they might otherwise have been able to go home.

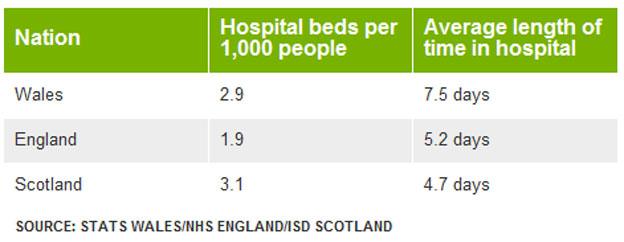

At the same time, however, Welsh patients also spend much longer on average in hospital, and the Welsh NHS has more hospital beds per person.

BBC Wales' health correspondent Owain Clarke reports

Both facts suggest that there may be significant scope for Wales to improve how people flow through the system, saving patients' time and increasing efficiency.

These figures suggest that despite its different decisions focused more outside hospitals, Wales has not so far moved ahead on reducing reliance on inpatient care and treating more people at home.

The prospects for the Welsh and English health services will continue to depend on population pressures, policy choices and, perhaps critically over the coming five years of austerity, investment decisions and the continued ability of the service to make savings.

Between 2009/10 and 2012/13 (the latest year for which comparable figures are available) Wales was the only country in which total identifiable health spending fell, from £6.28bn in 2009/10 to £6.01bn in 2012/13 (at 2012/13 prices).

In contrast spending in England rose slightly from £101.6bn to £102.2bn.

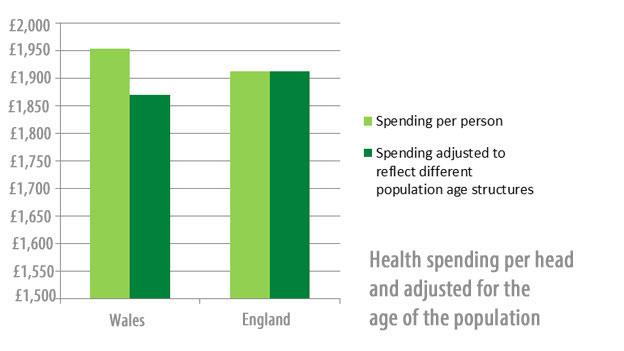

In both countries spending per head fell, reflecting growing populations, but that in Wales fell by 5.4% (from £2,066 to £1,954 per head at 2012/13 prices), compared with only 1.8% in England.

The picture may be even worse for Wales. The graph below examines how spending per head changes if it is adjusted for the different age groups in the population.

For example, if we know that a 30-year old tends to need 40% more healthcare than a 16-year old, we count the 30-year old as 40% more "population" among whom spending needs to be divided up.

After allowing for Wales' older population, it appears to spend less than England per "age adjusted person".

Notably, the NHS in Wales spends considerably less per person than North East England or Scotland, which have somewhat comparable populations. The gap with Scotland may be partly explained because the Barnett formula, which distributes funding across the devolved governments, does not take into account similarities or differences in population need.

It is hard not to conclude that such relative spending trends have had an adverse impact on service delivery, despite the savings made and the continued investment in social care.

October 2014: The Welsh government and the Daily Mail traded blows

The point of the political fight over the Welsh NHS is the idea that politicians are responsible for how well the health service is performing. They are blamed if things go badly (although rarely get the credit if things go well).

But is this the right way to understand why the Welsh NHS is under so much pressure, and what we might be able to do about it? The lack of comparable data means much is still clouded, but we think there are three points patients should consider:

Don't sweat the details. Since 1999 leaders in London and Cardiff have made countless ministerial statements, announced hundreds of initiatives and done plenty of tinkering with structures and management in the Welsh and English health services.

Nevertheless, devolution means a different path. While politicians have less control over the detail of health service performance than they (or their opponents) may claim, politics does make a difference when it comes to the big decisions affecting all public services over many years: what these services are supposed to do, and how much money they get to do it.

Under-funding threatens to reverse progress in every UK country. With the NHS under pressure across the UK, attention inevitably focuses on how the system measures up against totemic targets, like waiting times in A&E or ambulance response times.

On these measures, the Welsh NHS has been struggling for some time. But, as recent headlines have shown, services are feeling the strain all over the UK and we can expect continued breaches of these targets in England as winter pressures continue.

Given the tight funding of the Welsh NHS, and its history of different priorities, it perhaps isn't surprising that problems emerged there first.

Nigel Edwards takes a look 'under the bonnet' of the NHS in Wales

Arguing over past NHS performance in England and Wales can only take the debate so far.

There is no room for complacency in any of the home nations. With public finances under strain across the UK, local authority spending on social care set to fall even further, and demand for health services on the rise, it is clear that services - whether in Wales or in England - will not cope if they do not at least keep pace with population change.

At the same time each NHS needs to be made more efficient and better equipped to deal with future pressures. Both England, through its Five Year Forward View, and Wales through Mark Drakeford's prudent healthcare approach, now aim to address this challenge.

The Welsh health service has room to improve. It needs to reduce its dependence on hospitals, tackle difficult questions of whether services are in the right places, and perhaps exercise a more rigorous approach to performance management.

Rather than arguments over past statistics, what the people of Wales need is for their NHS to focus on making these changes for the future.

- Published29 December 2014

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015