Waterloo: Neath captain's memoirs depict battle

- Published

Gronow became well known around London as a founding dandy

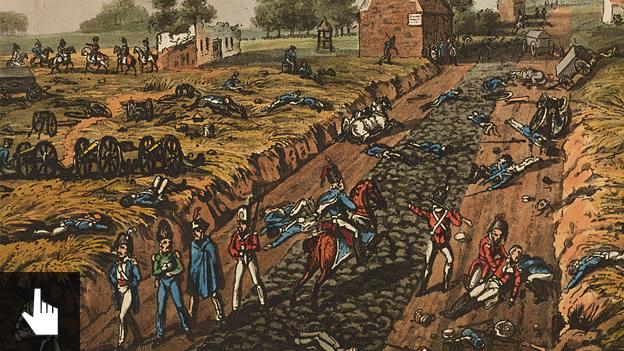

Two hundred years after Waterloo, one of the most vivid and visceral accounts of the battle is found in the memoirs of a man history seems to have forgotten about.

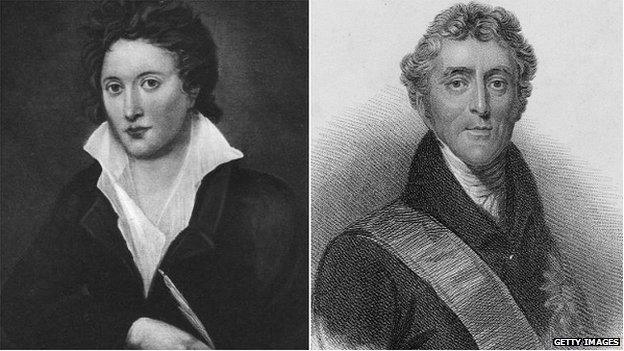

Born in Neath in 1794, Capt Rees Howell Gronow attended Eton and listed amongst his friends: the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, the Duke of Wellington, and the Prince Regent - the future King George IV.

Reputedly the second-best shot in the British Army, he was also a socialite dandy, and an inveterate gambler, duellist and womaniser.

He bribed his way into parliament and spent time in a debtors prison after losing the first of his two fortunes.

His four volumes of endearingly witty Reminiscences and Anecdotes were a kiss-and-tell on London and Paris society of which any modern tabloid would be proud.

They earned him a second fortune, which he promptly blew, leaving his young wife and four children penniless when he died aged 71 in 1865.

'Not boastful'

Gronow counted poet Shelley and Waterloo hero Wellington as friends

But despite his larger than life persona, former Guardian deputy editor and historian David McKie said Gronow's telling of Waterloo bears up to scrutiny against other contemporary sources.

"I first stumbled across his works in a second-hand book shop in Tunbridge Wells," he said.

"He was only 21 at Waterloo, so by the time of writing he was looking back on events over 40 years before.

"Nevertheless, his account of friends and comrades losing their arms, their legs, their lives, all around him feels real and immediate. It isn't boastful in the way of many other sources, and appears to be factually sound.

"He clearly wants to entertain with his writing, but you get the sense of a man for whom recording history accurately is important."

After the Napoleonic wars, together with Beau Brummell, Gronow became well known around London as a founding dandy; a group of fashionable young men who placed high importance on clothes, society and leisurely pursuits.

'Pithy frankness'

A fictional 'John Bull' at Cafe Tortoni in Paris - one of the illustrations in Gronow's books

They are credited with popularising the cravat and leading the switch from knee-breaches to long trousers, and are said to have polished their boots with Champagne.

But this extravagance came at a price, and on 18 June 1823 - the eighth anniversary of Waterloo - he was declared bankrupt and thrown into the debtors' prison.

"He shows admirable candour," McKie said.

"Writing with the benefit of age, he's refreshingly honest about the follies of his youth, and how he can see the same weaknesses leading to the ruin of those around him.

"Yet he's not apologetic either. He sees time in a debtors' prison as an occupational hazard for those who liked adventurous lives. After all, it wasn't seen as real prison, and inmates could have their meals, and even wives and mistresses, brought in.

"He demonstrates the same pithy frankness when, after describing how he lost his chance of winning a parliamentary seat at Grimsby because he wouldn't bribe the electors, he goes on to record how, in a subsequent contest at Stafford, 'I set out to bribe every man, woman and child'."

'Unquenchable gossip'

However, being an MP proved too much like hard work and Gronow soon retired to France where, aged 63, he married a Breton aristocrat 30 years his junior and had four children.

He was in Paris for the 1848 uprising which forced out Louis Philippe, and again for the coup in 1851 when Louis Napoleon seized power.

According to McKie, it was then that Gronow's memoirs truly came into their own.

"He writes like an unquenchable gossip, but with the authority of a man well connected in the highest echelons of society. His descriptions are acerbic, but softened with humour.

"In some ways he's a hard man to like; unthinkingly anti-Semitic and misogynistic, and in parts nauseously sycophantic towards Wellington. But in other ways he's a liberal who's ahead of his time.

"He is scathing about the failures of the officer class to deal decently with those they command, and talks in uncommonly sympathetic terms about the plight of the poor during the Paris uprisings."

He died in Paris on 20 November 1865 and, according to the Morning Post: "He left his widow and infant children wholly unprovided for."

But for a man for whom all publicity was good publicity, perhaps the bitterest pill of all for Gronow to swallow would be that 150 years after his death, hardly anybody remembers his name.

- Published29 April 2015

- Published11 April 2015

- Published4 April 2015