The Welsh women who fought Napoleon

- Published

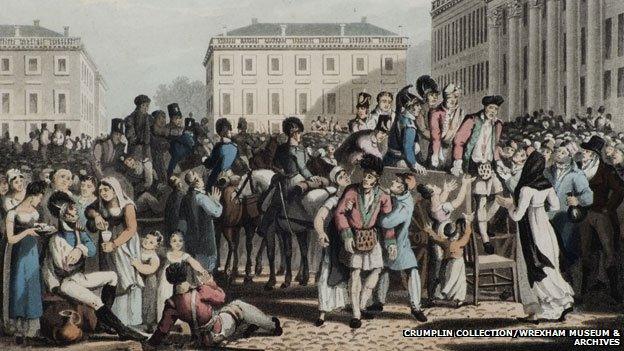

Women treating injured soldiers after the Battle of Waterloo in Belgium

On the eve of the Battle of Waterloo The Duke of Wellington is reputed to have said: "This army is composed of the scum of the earth. I don't know what effect these men will have on the enemy, but by God they terrify me."

But if he found "these men" terrifying, equally intimidating must have been the legions of Welsh women who had followed The Royal Welch Fusiliers (23rd Regt of Foot) ever since the earliest days of the Peninsular War - when Britain, Spain and Portugal faced Napoleon.

At times their amusing antics foreshadowed the so-called Wives And Girlfriends (Wags) who are alleged to have distracted from England's 2006 football World Cup campaign.

However for many of the wives, daughters, and even opportunistic cooks, washer women and prostitutes, the reality of life on the front line often proved tragic beyond belief.

Swansea University historian Dr Gerry Oram explained: "Officially six women were permitted to travel with each company of a hundred men; these were drawn by lot.

"But of course far more than this accompanied the army unofficially, and commanders's attitudes towards them varied according to the situation.

"They could prove extremely valuable, cooking, sewing and tending to the wounded, but at times - such as the evacuation of Corunna - they also became a major hindrance."

In a time before bank transfers, accompanying their men to war was often the only way wives could ensure they received any of the wages which were paid directly to the troops at the front.

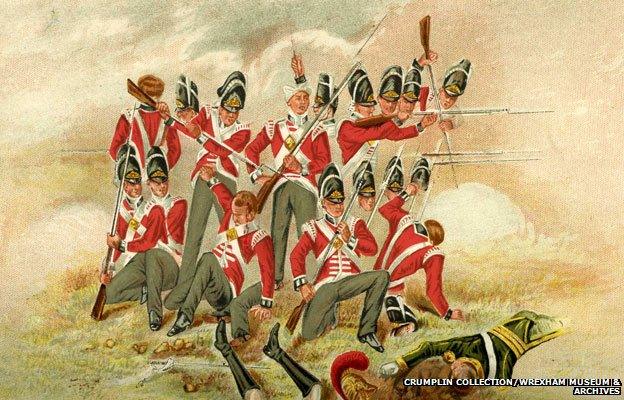

Wellington called the 23rd regiment 'the most complete and handsome military body I ever looked at'

They withstood an attack by the French cavalry at Waterloo

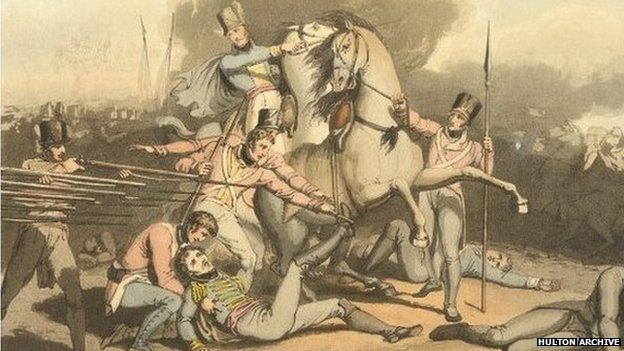

A scene from the peninsular war in 1809

A third of the Royal Welch recruits serving at Waterloo were Welsh, many young and from farming backgrounds

Also, with housing often linked to a job such as iron working or farm labouring, when men signed up for the army many women found themselves homeless, and without any choice but to join their husbands.

Some - such as Jenny Jones of Talyllyn - are even believed to have fought alongside their men.

But others contented themselves with the more traditional Wag pursuits of drinking, shopping and getting in the way.

In his history of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Donald E Graves wrote about how the women and children were left behind in Santa Marta in Spain during one action in 1808 by Colonel Sir William Beresford as his brigade moved forward.

"Since the women rarely obeyed any orders given to them, Beresford formed a guard across the road to prevent their joining the line of march," writes Graves in Dragon Rampant.

"After several hours of trudging in mud and snow, his brigade did not encounter any enemy, only their women 'who had with the perseverance of their sex out-manoeuvred the guard, got a Spaniard to guide them by a nearer route, and were quietly waiting our arrival in the morning at the turning of a cross-road."

Dr Oram believes the fact the women were able to move around with such impunity says a great deal about the age-old way in which the Peninsular war was still being fought.

"Even in the war that gave us the word 'guerrilla', set piece battles still dominated and there was a tacit, almost chivalrous, sense that the women were outside of the fighting.

"Whilst they could expect no special treatment, they weren't specifically targeted as a vulnerable point in the enemy, as you might expect would be the case in a modern war."

Yet even though only a handful of women died in battle, hundreds if not thousands perished as British fortunes took a turn for the worse in January 1809.

15,000 British soldiers died at Waterloo

As the army fled headlong through the snow for Corunna, the women who just a month before had simply been along for the ride, suddenly found they were now unable to keep up.

The official diary of the operations in Spain under Sir John Moore' notes: "Some were taken in labour on the road, and amid the storms of sleet and snow, gave birth to infants, which with their mothers, perished as soon as they had seen the light.

"Others in the unconquerable energy of maternal love, would toil on with one or two children on their backs; till on looking round, they perceived that the hapless infants of their attachment were frozen to death."

Of the 48 women and 20 children who travelled with the Royal Welch Fusiliers to Spain in 1808, only a handful are known to have come home.

Estimates put the overall number of British women who died on the march back to Corunna at possibly as high as 1,000.

Wives continued going to war right up until the Battle of Waterloo, but thereafter the practice began to die out.

Although an increasing number of women would join the front line in future wars, in professional roles such as nursing, the war against Napoleon was the last major conflict in which so many would travel purely as wives.

- Published10 June 2015

- Published2 April 2015

- Published30 May 2015