Nurse who helped 200 allies escape WW1 inspires historian

- Published

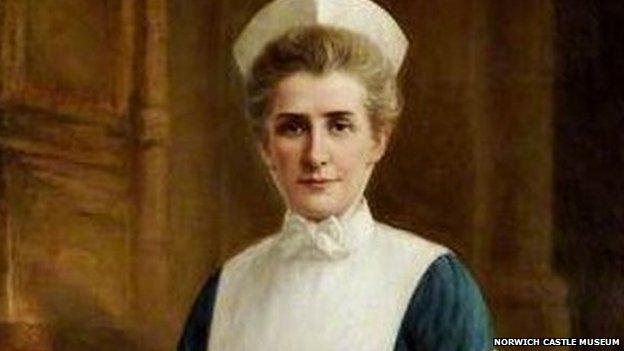

Edith Cavell was shot by a German firing squad in 1915

A relative of Edith Cavell - the British WW1 nurse shot by the Germans for assisting the enemy - says a Cabbage Patch doll, a lost postcard, and her ancestor's extraordinary tale all helped inspire her to study the role of women in justice.

Swansea University historian Dr Emma Cavell is descended from an uncle of the nurse, who helped around 200 allied men escape German-occupied Belgium in late 1914 and early 1915.

Edith's plight sparked outrage amongst neutral nations who had petitioned for clemency, and her image was widely used by Britain in anti-German propaganda posters.

After the war she was given a state funeral at Westminster Abbey, before her remains were reinterred at Norwich Cathedral.

Dr Cavell, who grew up in Australia, says she can still recall the moment when she first learnt of her family's history.

Dr Emma Cavell named her daughter, Edith, after a descendent who was a heroine of WW1

"As a child of about eight or nine, I was given a Cabbage Patch doll. They each come with their own name tag, and this one happened to be called Edith. I remember my Mum telling me, 'you had a relative called Edith'.

"Long before meeting and marrying a Cavell, mum had learned about nurse Edith at school in Melbourne.

"My grandfather, who was born the year after she was executed, remembered seeing a postcard Edith had sent to his father. It was long-gone by the time I came along, but I remember wishing I could have read it.

"After that I became fascinated with all things historical, but especially women's history because so often it is hidden away.

"I even called my own daughter Edith."

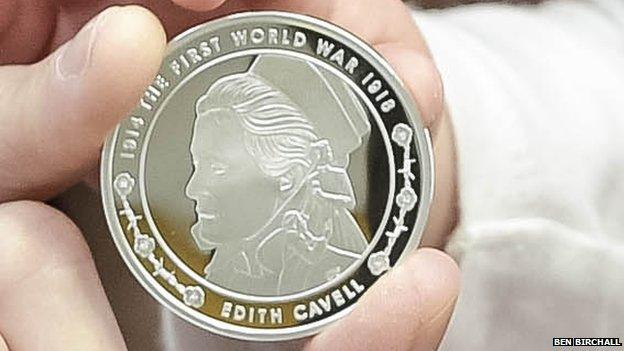

A special edition £5 coin has been created to commemorate the centenary of Edith Cavell's execution on 12 October 1915

Edith Cavell was the daughter of a Norfolk vicar, born in 1865.

She never married, and at the outbreak of WW1 she had been nursing at the Berkendael Medical Institute in Brussels for a decade, where she had already established a formidable reputation as a matron.

A devout Christian, she made no distinction between the German and Allied troops on her wards, saying: "I can't stop while there are lives to be saved."

But behind the scenes she was providing forged papers and cash to help stranded British soldiers and Belgians of military age make it over the border to neutral Netherlands, and then back to Britain.

After her capture she was variously portrayed in the media as both a daring spy and as a damsel in distress.

But according to Dr Cavell neither depiction of her ancestor is entirely accurate.

"Despite the posters of a helpless young girl lying on the ground while she is shot in cold blood by a callous German, the truth is that Edith was a tough 49-year-old woman who knew precisely the danger she was placing herself in.

"She admitted quite frankly what she'd done, and doesn't appear to have been afraid of the consequences.

"But nor have I seen anything to support the idea that she was involved in the intelligence services. I think she was simply a principled woman who was determined to do what she thought was right."

Dr Emma Cavell is a descendent of nurse Edith Cavell who helped around 200 allied soldiers escape German-occupied Belgium

Dr Cavell's research at Swansea University is on the role of women in the justice systems of medieval and early modern Britain.

However she says that there are still parallels with Edith's case.

"You see the same themes repeating themselves; women caught up in a system over which they have little overt or direct control.

"But just because they weren't in the front of house military and political roles, you shouldn't overlook how women like nurse Edith influenced events from behind the scenes.

"The same part Edith played on the Western Front was being played by apparently anonymous women in Wales during Edward I's conquest, over 600 years earlier."

Edith Cavell has been remembered in a special edition £5 coin, minted to commemorate the centenary of her execution on 12 October 1915.

- Published5 July 2014

- Published12 July 2014

- Published16 May 2014