SAS deaths: The savage beauty of the Brecon Beacons

- Published

The Brecon Beacons is the chosen testing ground for one of the most revered fighting forces in the world - the Special Air Service.

A deceptive and gruelling environment, the deadly extent of its pitfalls was brought into sharp and shocking focus on Saturday 13 July, 2013.

Early morning, three supremely fit, experienced soldiers set off on a 16-mile timed march.

It was a relatively short exercise in a series they had volunteered to undertake in a quest to being accepted into "The Regiment".

None of them made it back.

A month-long inquest into why these soldiers collapsed delivered a conclusion of neglect on Tuesday.

Here BBC Wales news website takes a closer look at one of Wales' last true wildernesses, its significant role in the history of the SAS and why it is no stranger to tragedy.

On bank holiday weekend August 1900, five-year-old Tommy Jones left home with his father, a young Rhondda miner, to visit his grandparents' farm in the Brecon hills.

Wearing new boots, his best sailor suit and collaret, they caught the train to Brecon before they both set off on a four-mile walk to the farm set in a deep valley below the highest summit in south Wales, Pen-y-Fan.

With only a quarter of a mile to go, Tommy and his father stopped at the Login, a building now in ruins but then a busy camp for soldiers training at a nearby rifle range.

Mr Jones bought a drink from the canteen and a penny's worth of biscuits for his boy.

Back to the Hills: SAS veteran Rusty Firmin recalls his own fear of failure during his selection in 1977

As fate would have it, they met Tommy's grandfather and cousin, William. Serendipity. Or so it seemed.

The men decided to have another drink and 13-year-old William was told to run to the farm and warn his grandmother to expect guests. An excited Tommy followed him.

Just a few hundred yards along, he began to cry. More at home in the terraced streets of the valleys, Tommy became frightened by the hills. His cousin told him to go back to his dad.

Around 15 minutes later, the cousin returned to the camp from seeing his grandmother. "Where's Tommy?" Mr Jones asked.

Obelisk near Pen-y-Fan in memory of Tommy Jones. Inquest jurors - who recorded he died from exhaustion and exposure - donated their fees to help pay for it

It wasn't long before soldiers joined the search - the first of 29 days of scouring the hills in a drama that captivated the entire nation and its newspapers.

A gardener's wife, who lived near Brecon, claimed the Daily Mail's reward for finding Tommy.

She had dreamed of his whereabouts and shrugged it off. But the dream played on her mind and a few days later she persuaded her husband to borrow a pony and trap for the long trip across the Beacons. She found Tommy's remains exactly where she dreamed they would be.

In his panic and fear, Tommy had climbed a staggering 1,300ft onto a ridge above the Login. No-one had thought to search so high, dismissing it as beyond the reach of a small child.

Anyone growing up around the beacons learns the story of Little Tommy Jones at an early age. It never leaves you. It's designed not to; a heart-breaking reminder that the beguiling beauty of the hills belie a ruthless, capricious nature.

Pen-y-Fan - which means 'highest of this place' - stands 886 metres (2,907 ft) above sea-level

On Saturday July 13, 2013, perhaps for the first time since the tragic events of Tommy Jones over 100 years before, the nation's attention shifted once again to the Brecon Beacons. The same question was asked: "How on earth could that happen?"

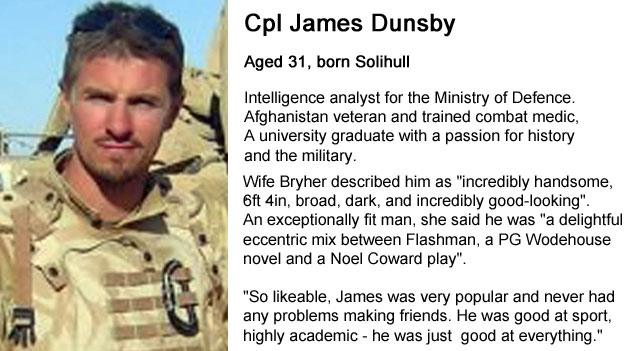

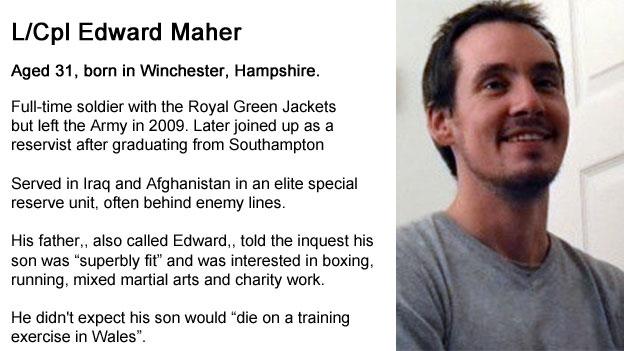

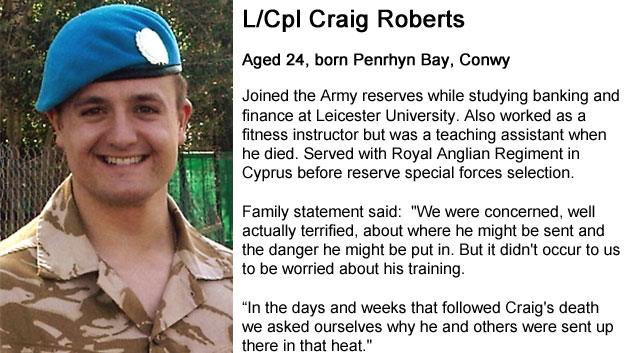

Corporal James Dunsby, 31, Lance Corporal Craig Roberts, 24, and Lance Corporal Edward Maher, 31, were men in their prime. They were supremely fit, intelligent and determined reservists with recognised military experience.

When they started the 16-mile march on what the Met Office forecast to be one of the summer's warmest days, they had no reason on earth to expect it to be their last. No one did.

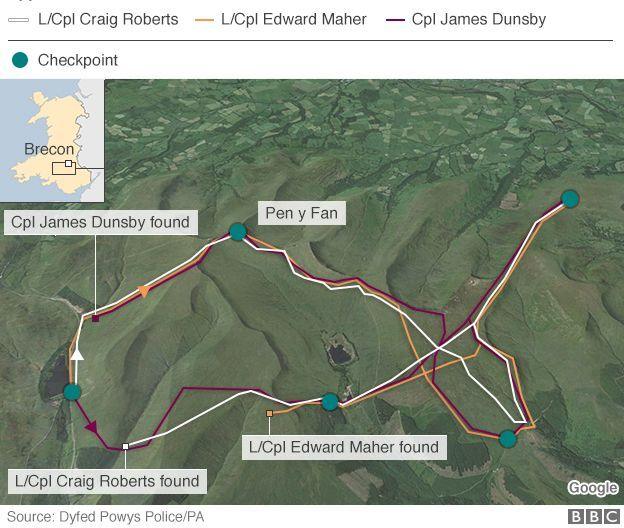

Throughout the day, all three men - part of a 78-strong mixture of reservist and regular soldiers trying out for the SAS - made good progress, passing through checkpoints to pick up grid references for the next rendezvous point.

The soldiers collapsed during the march while carrying 50lbs (22kg) of equipment

All three were on course to complete the march within time. Then, one by one, their GPS trackers became static.

When help eventually reached Edward Maher, rigor mortis had already set in. His body was in a seated position, a bottle of water in one hand, a half-eaten chocolate bar in the other.

Shortly before, Craig Roberts was found convulsing by another soldier. Despite medical help, he was pronounced dead on the hills at 1710 BST.

James Dunsby was tantalisingly close to the finish near the busy A470, when he collapsed. He died two weeks later in hospital.

Roberts and Maher died of hyperthermia. Dunsby died of multiple organ failure as a result of hyperthermia.

James Dunsby (far right) with Prince Harry and his fellow troops in Helmand Province, Afghanistan

The arguments about what exactly led to their deaths continue to rage: lack of acclimatisation; not enough water at checkpoints; MoD guidelines not being followed; lack of risk assessments prior and during the march; unreliable GPS tracking; poor contingency planning; delayed medical help, and so on.

Regardless of who or what is right, few disagree that something went terribly wrong that day.

"I was surprised to find three had died on one selection," said Rusty Firmin, the man who brought the SAS to the attention of the world when he played a lead role in one of the regiment's defining moments - the storming of the Iranian Embassy following a six-day siege in London in 1980.

"I can't remember that ever happening before.

"Heat exhaustion is easy to spot if you're looking for it. I'm certain the instructors on that day, as with any other day, would have been looking for signs.

"I've worked all over the world in 100-plus countries on every continent and actually, how many people have I known who have suffered with heat sickness? I can probably count the number on one hand."

Rusty Firmin, author of two books on his 15 years with the SAS, says the Brecon Beacons are highly valued by the Army

Former SAS sergeant and novelist Andy McNab is just as baffled.

"Clearly something went wrong which needs to be rectified," he said.

"Every soldier knows from day one that the only important things in the field are ammunition and water. You can't survive without them so you're aware of their importance.

"With this in mind, I find it very hard to understand why the guys, who were issued with water bottles, got into this state."

They were not the only candidates to get into that state.

Army reserve SAS candidates are usually ex-regular Army or in the TA although 25% join with no military connection

Just a few hours into the march, the first of seven cases of heat sickness that day were identified.

The inquiry into the men's deaths heard accounts from walkers flagged down by distressed soldiers, not those who subsequently perished, who pleaded for water.

Soldiers are a common sight on the Beacons. They have been for centuries. This is an area whose military history dates back to Roman times when it served as a cavalry base.

Army camps remain at Sennybridge and Dering Lines, the Infantry Battle School Brecon - former regimental HQ of the legendary South Wales Borderers whose stand at Rorke's Drift was immortalised in the film Zulu.

The remains of a number of other long-abandoned training camps, rifle and live firing ranges, are slowly being reclaimed by nature.

Elsewhere around the 500 sq miles of Brecon Beacons National Park, the strewn and rusted wreckage of some 40 warplanes which crashed mainly during the Second World War, are yet another reminder of the hazards unleashed by the hills' unique weather system.

This subject of the weather was of course central to the inquest into the soldiers' deaths. It opened in June this year when Coroner Louise Hunt was told the weather that day was "freaky".

But sub-zero or stifling, it is precisely this spectrum of uncompromising, disorientating conditions which is so valued by the Army.

Speak to anyone who knows the Beacons and they will tell you 'things turn on a sixpence up there'.

"It can be like the Costa Del Sol down by the Storey Arms car park," said Ken Jones, organiser of the Fan Dance (named after Pen-y-Fan) an annual endurance event inspired by SAS selection.

"You go a few hundred metres up and the wind and hill fog can come in and it can be raining heavy and you can come undone very quickly."

Former Paratrooper Ken Jones says the will to succeed is an "indomitable force" which is difficult to control

So why exactly is the weather so testing and unpredictable?

The Beacons are the first land mass the jet stream hits as it rolls off the Irish Sea, explains Brecon Mountain Rescue's Mark Jones.

"On a clear day, because the Beacons are the highest point in the area, you can see the weather rolling like a cloud bank off the coast.

"I think the time it catches people out is when there's already established cloud but it's higher than the peaks. Then, suddenly, the cloud drops. There's a temperature change, visibility is gone.

"That can happen within 10 to 15 minutes with visibility reduced from 'as far as the eye can see' to just 15ft."

These unpredictable conditions ensure the month-long selection marches - held twice a year, summer and winter, and followed by five months of 'continuation training' - are not only used to test physical fitness, but something arguably more important - strength of mind.

"You've got fairly miserable weather, highly demanding terrain and the shape of the landscape requires, in many instances, careful route selection to ensure it doesn't just become a physical exercise," says Ken Jones, a serving Paratrooper when he undertook SAS selection.

"It's a mental one too, with the candidate required to think and he's ultimately responsible for his own actions on this individual, self-sustained march."

The Brecon Beacons has a strong connection with the military dating back to Roman times

Recalling his first attempt at selection which he failed, Andy McNab said: "It's extremely hard."

"Literally it's every day, you've got to travel between 15 and 64km with a bergen (backpack) weighing between 35 and 55lbs. And you've got to go from one checkpoint to another and cover the distance as quickly as you can because you don't know the cut-off time for that day's tab (march).

"For me it wasn't the physical side of it, it was the mental endurance.

"You can't gauge yourself against other people because other people are doing different routes. It's all about your own best efforts and that was very, very hard. You just had to keep going."

Ken Jones said he nearly died due to exposure at night during his selection month's final 40-mile march called the Long Drag.

"I was in serious trouble and I remember my thought process," he added. "It wasn't 'oh my God, I might die'. It was 'oh my God, I might fail selection'."

"That's an indomitable force. What can you do to vanquish that? I've heard accusations from candidates who've failed the course that a more careful and intelligent form of man management is required to control that do-or-die attitude.

"How do you control an urge like that? If someone doesn't particularly care about dying at the time and they want to continue at all costs?"

That same urge, he explained, can lead to candidates becoming accomplished actors at checkpoints, bluffing their way through questions designed to expose problems like heat illness which would result in their instant withdrawal.

And that is one thing the most determined candidates fear above anything else.

So with all the extremes of weather in mind, the uninitiated might think a hot July day is preferable to a cold and wet one in February.

But then 13 July was not just warm. It proved to be one of the hottest days of the year; the temperature reached 27C.

Nathan Webster, a keen hill walker from Cardiff, was around Pen-y-Fan that afternoon.

"It was roasting," he recalls. "Even at 4 o'clock, the heat was searing, pumping down on me. You could feel it burning your skin.

"On parts of the ridges you could see heat thermals moving around the valley. It was as if heat was trapped there. There was no air, absolutely no breeze."

Mr Webster had climbed onto to a high ridge with a panoramic view of the central Beacons area when he heard a helicopter.

"Through my binoculars I could see they were Army," he said. "I could see the helicopter was there and a couple of guys were crouched down, not moving.

"To the left of them was a big group of people. They were gathered round an area with what looked like large rucksacks or even body bags dotted around.

"At that distance it was hard to make out what had happened but I knew it was something bad."

Nathan Webster, a walker from Cardiff, witnessed rescue attempts on one of the three men who died

It was not until much later that Mr Webster heard reports of heat sickness. Heat sickness? This was the Welsh countryside. We're hardly a nation famed for its problems with excessive heat.

That could have been part of the problem. The inquest into the soldiers' deaths heard that the majority of heat illness cases actually happen in temperate climates, like the UK.

Leaving aside factors like genetics which can play a part, soldiers, particularly the reservists, may not have had much opportunity to acclimatise to such intense heat, the inquest heard.

It is also possible the soldiers appeared to be functioning normally, until it was too late.

"Heat exhaustion can hit pretty quickly," explained Professor Brent Ruby, an expert in heat stress and human endurance at the University of Montana, USA.

"Especially in a population bent on really pushing themselves. Often they can push through the initial warning signs and initial discomfort and then quickly get into trouble."

So how do troops manage to cope in intensely hot environments such as the desert and not cope in the Welsh hills?

"The difference between the real world combat scenario and this scenario is the work rate," he said.

"The work rate in this selection scenario is considerably harder than they could expect to find in the majority of their operations. Just because of the duration and metabolic load created by this event."

He added that the fact that the soldiers were against the clock also meant they were unlikely to have had sufficient time to cool down properly.

"People constantly think 'Oh, if I just drink enough water, I'll be fine," he said. "'I can do whatever I want, run at this pace, hike at this pace and not have any problems'. That is a major misconception.

"The number one way to prevent or reduce risk is to slow down to enable the body to offload heat - remove clothes, shade, rest, then a distant next stop is cold water.

"If this doesn't happen it ultimately leads to an unusually high skin temperature and when that starts to encroach on the internal body temperature, or may even exceed it, that's when you get into a very dangerous situation.

"They can't offload heat and it just builds and builds and then the core temperature soars and then they collapse."

Earlier this month, the man who was director of UK Special Services in 2013 gave evidence at the inquest into the deaths.

Soldier EE, as he was referred to, said he was "very aware" of heat injuries; he had served in Afghanistan where temperatures hit the 40s and low 50s.

He was then asked about the Ministry of Defence's code of practice on heat illness set out in a document entitled JSP539

This document states that in the case of heat illness, an activity should stop if operationally possible. Had this been adhered to, the march on July 13, 2013, would have been called off after only a few hours as two other men were withdrawn due to heat sickness after midday.

This, the coroner, said would have saved the lives of Craig Roberts, Edward Maher and James Dunsby.

Soldier EE was asked about organisers of the march admitting to the coroner that they were not aware of that document.

"It wouldn't surprise me," he told the hearing.

"It would not at first glance appear relevant to a rigorous march in the Welsh mountains," adding that he would, however, be surprised if they were not keenly aware of symptoms of heat illness.

As if the point needs to be pressed home anymore...

It does not matter who you are - five-year-old Tommy Jones or an special forces soldier - getting caught on the wrong side of the treacherous terrain of the Brecon Beacons with their capricious elemental forces, never ends well.

Additional reporting: Delyth Lloyd