Wales' role in the birth of the atomic bomb

- Published

Welsh scientists helped lay the foundations for the birth of the atomic bomb

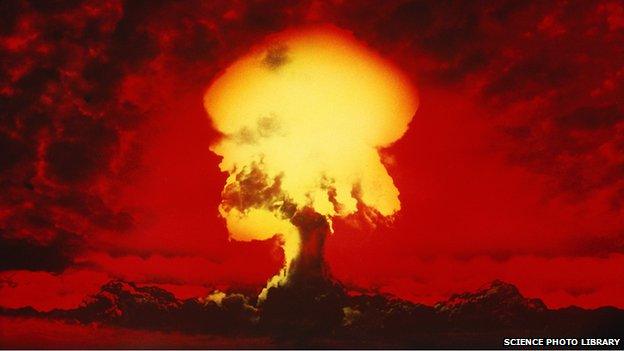

Seventy years ago scientists waited nervously in the New Mexico desert for the largest explosion in the history of mankind.

It was the Trinity test - the first detonation of the atomic bomb. Three weeks later it would be used to devastating effect over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

What is less well known is the role Wales played in bringing the world into the nuclear age, long before American research had even started.

At Flintshire's top-secret Rhydymwyn Valley Works near Mold, the "Tube Alloy" project was under way - where scientists developed the key process that made nuclear warfare a reality.

At the start of World War Two, the tunnels in Rhydymwyn Valley were a giant silo for storing mustard gas, which would have been dropped on the British coastline in the event of a German invasion.

Towers at the Rhydymwyn Valley site

But already thoughts were turning to an even more deadly weapon.

In 1941, the Maud Report established a nuclear bomb was theoretically possible and, in all likelihood, Germany was already working on one.

A site, known as Building 45, at Rhydymwyn was identified as the ideal location to begin tests, and as Colin Barber, chairman of Rhydymwyn Valley History Society said, what scientists discovered there would change the world forever.

"They knew the bomb was possible, what Tube Alloy was set up to discover was whether it could be made in time, and at a price a war-torn Britain could afford," he said.

"Fifteen to 20 kilograms of the radioactive isotope Uranium-235 were needed for the bomb, but U-235 only constitutes about 0.7% of uranium ore.

"The scientists at Rhydymwyn perfected a method of extracting this from the ore by turning it into a gaseous form of uranium (uranium hexafluoride or hex) in a heated chamber and forcing it against a very fine meshed membrane.

Building 45 - home to the Tube Alloy project

"Using this method they predicted they could produce enough to manufacture three bombs per month in two years' time."

In 1942, Britain led the way in nuclear research, but the costs - both in terms of money and scarce resources - proved prohibitive.

So Britain shelved its hopes of developing its own nuclear weapon, and instead reluctantly pooled its expertise with America's Manhattan Project.

It heralded a fractious and suspicious period in Anglo-American wartime relations, though many of the Rhydymwyn scientists, such as James Chadwick and Mark Oliphant, did cross the Atlantic to contribute to the eventual bomb.

Meanwhile, research at Rhydymwyn was scaled back, and eventually mothballed in 1945.

After serving as a Cold War logistics and storage depot, now the works have been transformed into a nature reserve.

Building 45 is Grade II-listed, and Mr Barber is campaigning to have its wartime role officially recognised.

Munitions were stored at the secret facility near Mold

"The creation and use of the atom bomb is always going to be contentious," he said.

"It killed and maimed hundreds of thousands of people, but arguably saved millions more by bringing the war to an end and preventing another.

"But whether you're for it or against it, the incredible achievement of a handful of scientists on a shoestring budget does need to be remembered in some way.

"I'd like to see a plaque erected there, so that future generations can both learn about the engineering feat, and remember the cost at which it came."

- Published4 July 2015

- Published5 August 2013