Fears for specialist language help for pupils in Wales

- Published

Dr Jonathan Brentnall explained what he thinks schools need to do

There are worries that changes to funding could hit specialist support for 23,500 pupils who do not speak English or Welsh as a first language.

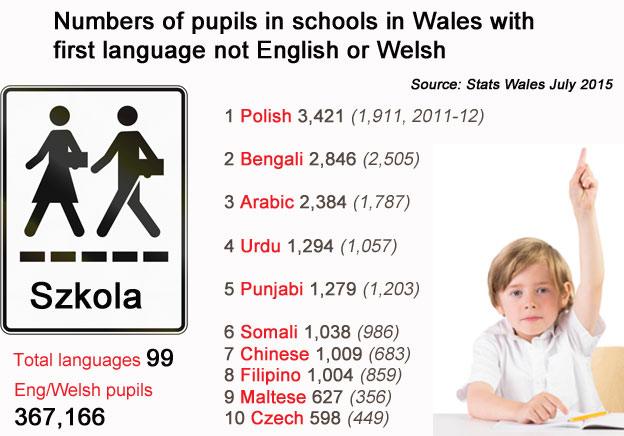

It comes as Polish-speaking pupils have overtaken the number of Bengali-speakers in schools in Wales.

One independent analyst fears a "significant loss of specialist expertise and support".

Ministers said despite tough times they were "proud" of increased funding going to schools.

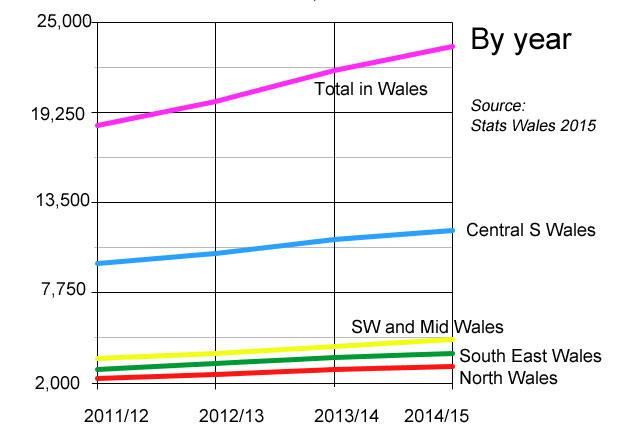

The latest statistics for numbers of pupils in schools whose first language is not English or Welsh shows a 27% rise since 2011.

There are 3,421 Polish-speaking pupils, 575 more than Bengali-speakers.

But as the landscape in the types of languages spoken has shifted, so has the way specialist help for pupils is funded.

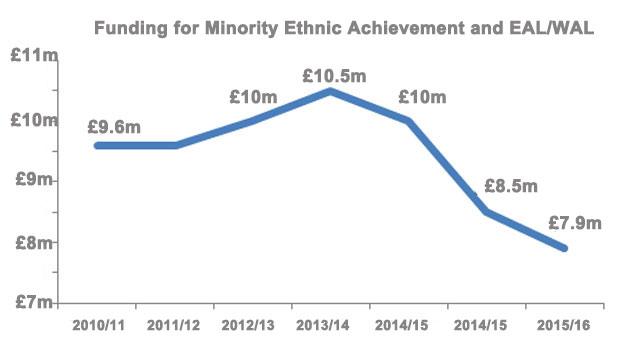

Since 2014, there has been a reduction in funding to support pupils learning English and Welsh as additional languages (EAL/WAL).

Then in April 2015, the Minority Ethnic Achievement Grant was merged with a number of other Welsh government grants into the more general Education Improvement Grant which is now managed by four consortia of local authorities.

This shows the top 10 of languages spoken

The old funding arrangements, in place for nearly 50 years, have involved most local authorities employing a specialist central pool team of staff at councils to work in schools and assist pupils with language development and curriculum learning.

There are worries with money no longer ring-fenced by councils, that support could be cut back and the flexibility lost to respond to changes in pupil numbers and needs.

One independent analyst wants ministers to ensure that funding is protected and prioritised.

Dr Jonathan Brentnall says that almost 90% of schools in Wales now have at least one pupil of minority ethnic background on their rolls and many of these are additional language learners.

He says some schools have little or no past experience in meeting EAL/WAL pupils' needs and with less specialist expertise available they may struggle to do so.

While, particularly some urban schools are well established in teaching children with different language backgrounds, there is a danger that if more funding is delegated to school budgets, those with smaller numbers will not spend the resources on specialists and training that are most needed.

"Discussing with colleagues, there seems to be a tipping point of about 25-30% of EAL/WAL pupils on roll, when schools begin to see them as a priority," said Dr Brentnall.

"Schools with smaller numbers do not often regard EAL/WAL as a significant enough issue to prioritise it for whole school development," he warned.

There has been a reduction in funding since 2013/14, including two drops in one year

Dr Brentnall, who once chaired the Welsh government's advisory group on ethnic and cultural diversity in education, said schools need to be aware that support for language development needs must go beyond the initial bedding-in period.

'Disrupted'

"It's not just about giving intensive language support for a few months. The process can take anything from five to 10 years for pupils to reach a level of proficiency that enables them to get to A* to Cs at GCSE. They need ongoing support in relation to grammar and vocabulary," he added.

"Some pupils are coming from war-torn countries like Iraq, Libya or Syria and have had their education disrupted. Such pupils may have a range of varied needs and it can take longer for them to catch up."

CASE STUDY - THE KUJAWA FAMILY

Kinga Kujawa explains how her five-year-old son Alex has grown up bilingually in Cardiff

Kinga Kujawa came to Cardiff in 2007 and both her and her husband work full-time and have two sons born here.

Alex, five, speaks Polish at home and English at his Catholic primary school, which has several Polish-speaking pupils.

"He reads and writes in both languages," says Ms Kujawa. "We picked the school because we were told the head was fantastic and one-to-one help was there if needed but Alex was reading and writing by the age of four. We speak Polish to him but he watches English telly. After three or four months in reception class at school they classed him as more able and talented and so he was already doing some year one work."

"If he's running around playing with friends, it's English you can hear a lot."

Alex also goes to a Polish Saturday school across the city so he can continue to learn about his parents' native language and culture.

Dr Brentnall said with the right help, many have the work ethic to achieve at least as well as their peers.

The National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum (Naldic) said the issue was UK-wide and a joint survey with the NUT had found more than 50% of schools and councils had reported cutbacks or wholesale scrapping of EAL specialist provision.

"These cuts are a trend across the different nations in the UK," said chair Dr Yvonne Foley.

"Given the current discourses surrounding migration across the country, EAL is often positioned as a political and economic issue.

"As a result, funding for EAL pupils lacks political and economic importance and this has implications for our education system as a whole when we consider issues of equality, social justice and long-term social impact."

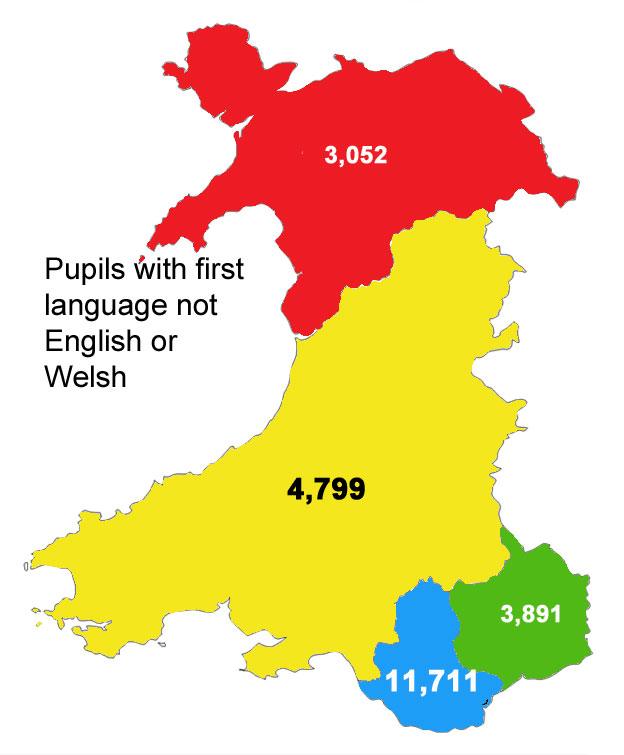

The number of pupils with English or Welsh not as a first language has been rising since 2007

Last year, the education minister acknowledged funding was tight but called for councils to be innovative in continuing to look for improvements., external

Head teachers in Cardiff have already written to him expressing concern.

The Welsh government said its new, simplified Education Improvement Grant allowed councils more flexibility to target resources at areas of greatest need and it was a "significant investment" when used efficiently and effectively .

A spokesperson added: "The new grant provides that flexibility for supporting learners from ethnic backgrounds and for whom neither English or Welsh is a first language by reducing bureaucracy and administration costs and enabling funding to be diverted into frontline support."

- Published30 July 2014

- Published23 June 2011

- Published16 November 2011

- Published22 April 2015

- Published23 December 2011