From dog grooming salon in Cardiff to a warzone in Iraq

- Published

Explosives sniffer dog enjoying his retirement after being brought home from Afghanistan

Chasing suspected gunmen in Northern Ireland, being shot at by militants in Afghanistan and tackling suicide bombers in Iraq were hardly roles Simon Mallin had in mind when he decided at a young age he wanted to work with dogs.

These environments were a world away from the kennels his parents ran and the pet shop and dog grooming salon he grew up above on Cardiff's Cowbridge Road.

But they acted as the catalyst for him setting up the Malpeet K9 Academy, where he trains unwanted dogs from around south Wales and former military personnel to detect bombs and drugs in the kind of hostile locations he was thrust into with little preparation.

Using live explosives, mock captures, interrogations and the scenario that Wales is gripped by civil war, animals and people are now readied for danger zones in the hills around Blackmill, Bridgend county.

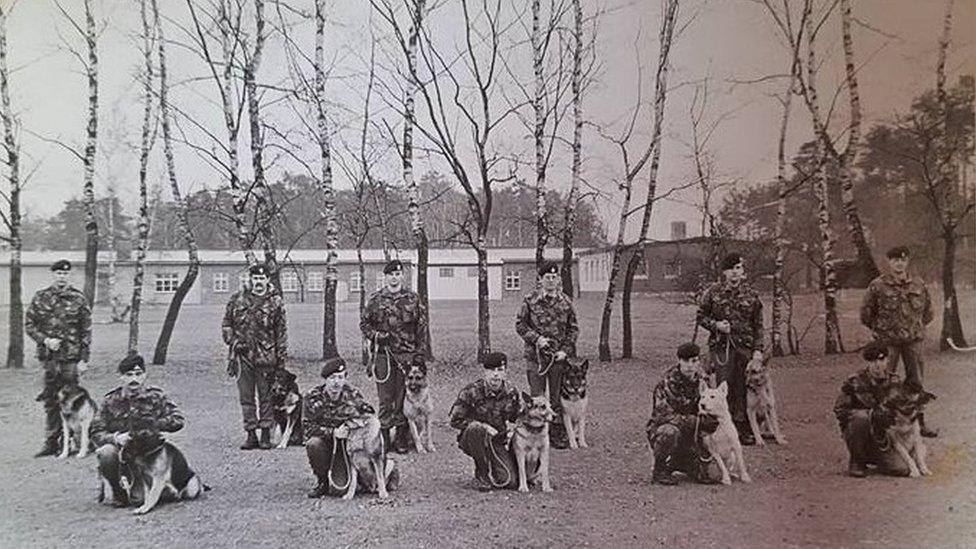

Mr Mallin, aged 19, back row third from left with the Army Dog Unit in Germany in 1987

'Fire fight'

Dogs were all the 47-year-old "really knew", from the poodles he watched being groomed in his parents' salon, to those he began showing at the age of 10 and the working dogs he kept when he began shooting as a teenager.

When he joined the army at 17, he says it was in the belief he would be able to work as a dog handler, but after being "misled" by an advisor at the careers office, ended up in the Royal Regiment of Wales' infantry division.

But he "nagged and moaned" and was eventually given a role with the Army Dog Unit patrolling prisons in Northern Ireland. This led on to work helping to hunt down suspected criminals, including one who had shot an off-duty worker on a military camp.

"The gunman had ran off and I was flown out to the area he was last seen," Mr Mallin said. "I was met by soldiers and then tracked him for a few miles before there was a fire fight and he was arrested."

After leaving the army in 1995, he trained dogs to detect explosives and work as tracker dogs for the military in Mindanao, Philippines, before embarking on what he describes as his "baptism of fire".

Mr Mallin was in Iraq from 2003 to 2008, working at Baghdad Airport and in Fallujah, providing security to building projects

Manning a checkpoint at Baghdad Airport in Iraq, he had to find suicide bombers among thousands of civilians travelling on a road that had "four or five lanes, like the M4 into Heathrow".

"We parked the cars up in line and used the dogs to search for explosives. It really was taking your life in your own hands because if the dog indicated they had explosives, they were likely to detonate," he said.

"Even if they were talked out of it or dead, the bomb was still strapped to them and someone else could detonate. I really had to learn on my feet."

While it proved impossible to stop many devices being set off, he said the checks helped keep vehicles as far away from the airport as possible, limiting casualties.

But he describes his "scariest job" as an assignment in southern Afghanistan in 2009, working with the Canadian military, who were overseeing a project to build a new road through an area where bombs were constantly being planted by saboteurs.

"Every morning, I would search a two mile stretch for explosives so the area could be secured and the road laid," he said.

"I was working with new dogs, under pressure and in the open, coming under attack by small arms fire quite often. Luckily they were pretty bad shots."

Mr Mallin was living among 200 Afghan nationals, many ex Taliban fighters and described the whole experience as "wild".

"I was told as long as the pay got through to the Afghans, I'd be okay, but quite often it would get ambushed.

"They would take drugs at night and be off their faces, brandishing weapons. I would lock myself in my shipping container and come out in the morning."

Mr Mallin and Tyler in Iraq

These experiences are behind the Malpeet K9 Academy, where he works alongside four full-time staff and Tyler, the 11-year-old springer spaniel he spent four years with in Iraq and was able to bring back to Wales in July last year with the help of a charity.

Dogs are trained to work in security as well as to sniff out explosives and drugs, while former military personnel are given "hostile environment training".

Mr Mallin had no preparation for what he faced, having to "learn on the ground" and he now wants to ensure others are as ready as possible.

About 30 people - a mixture of novice handlers and former army, navy and RAF personnel - attend the 32-day residential explosive search course each year.

"When they arrive, they think there may be a slow start in the classroom, but we set the scenario straight away that Wales is on the brink of a civil war, with there a disputed road that two factions are fighting for."

Other unexpected challenges include participants being asked to find their own way to a location in France, where they learn how to fire AK47 rifles and M4 and M16 pistols.

"It culminates in an exercise where a forward operating base is set up in a horse shed. They have to build defences and secure and search a road. Many are already dog handlers, but based on my experience in Afghanistan, we want them to be ready for things they don't expect."

Sleep deprivation, mock captures and interrogation with military specialists are also thrown in, proving careers working with dogs are not always as straightforward as some may imagine.

Images and video

By Michael Burgess and Philip John

- Published2 October 2015

- Published9 November 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published12 July 2012