Why is Port Talbot steelworks important?

- Published

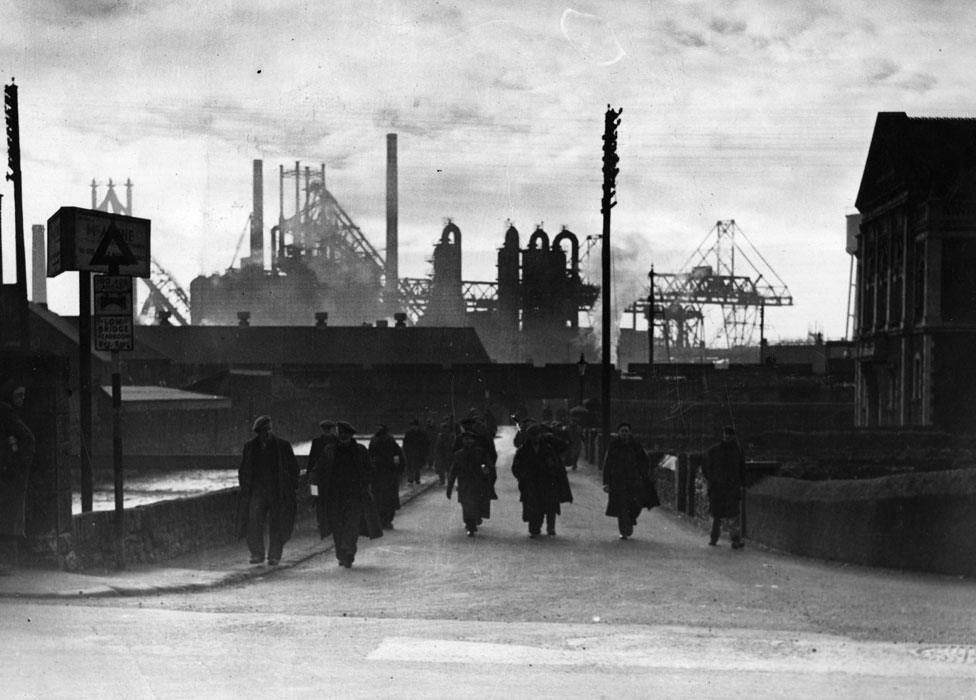

Port Talbot in its heyday in the mid 1960s

The town of Port Talbot has for more than 60 years been synonymous with steel.

The sprawling works span the horizon as you drive along the M4.

In its heyday in the 1960s, nearly 20,000 people worked there. The town grew up around it.

Numbers may have dwindled but even with a 4,000-strong workforce, it still has an imposing presence in the Welsh economy.

It is still Tata Steel's biggest UK operation and one of Wales' economic crown jewels.

Another 3,000 work at Port Talbot's sister plant in Llanwern and at Shotton and Trostre.

It might be the car we drive, the tin cans for our food or the washing machine in our kitchen, but the chances are we have a piece of Port Talbot close to hand.

The steel plant has benefited from some significant investments in recent years, including £185m on rebuilding one of its blast furnaces.

But Tata has faced difficulties from different directions.

Port Talbot: The problems

Steelworks use huge amounts of energy. The Port Talbot plant uses as much electricity, for example, as the whole of the city of Swansea a few miles along the motorway.

That bill when it hits the metaphorical mat is a whopping £60m a year - 50% more than other plants in Europe. No wonder, looking long term, Tata recently secured the go-ahead to build a new power plant so it can generate more of its own power to save money.

Then there are problems in the market. Because of overproduction, the Chinese are now exporting twice as much steel to the UK than they did in 2013 and at less than the cost price of UK steel.

Tata is also unhappy about the level of business rates it pays, compared to European competitors.

In all, the plant is said to be losing millions of pounds a week.

Workers leaving the shift at the newly-formed Steel Company of Wales in Port Talbot in 1949

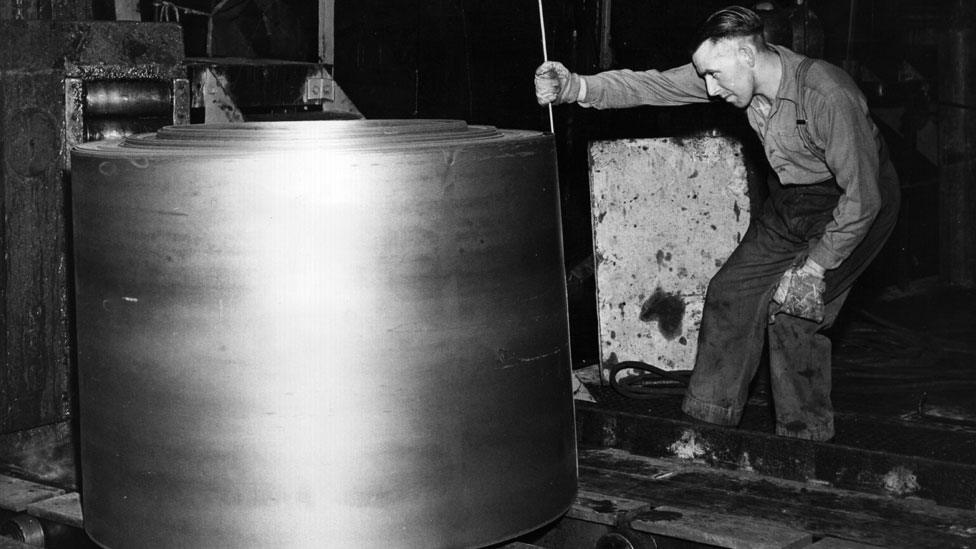

A worker in 1961 measures a roll of steel

Port Talbot in 1961

Why is steel still so important?

Port Talbot steelworks is a big employer and pays more than double the minimum wage - starting salaries are around £30,000 a year.

It puts £200m a year into the economy just in salaries.

Economist Prof Calvin Jones of Cardiff University has studied the impact of Tata , externaland called it "the most economically important private sector company in Wales".

The economic value of Tata - including the supply chain - was estimated at £3.2bn of output and £1.6bn of value added in Wales in 2010.

But it also supports an estimated 10,000 full-time equivalent jobs off-site.

"These are important [industries] because they are high value added and important because they're iconic," he said. "If we do see continued declines in these industries in terms of employment and output then you start to wonder what Wales is for."

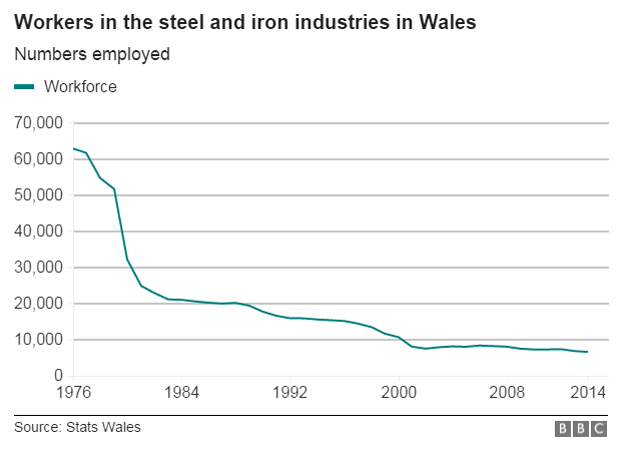

STEEL TIMELINE

1902: The first steelworks at Port Talbot is founded

1923: A second Margam works is finished

1947-1953: The third Port Talbot plant is built and becomes part of Steel Company of Wales. The works employ around 18,000. By this period, the rolling mill at Ebbw Vale has become the biggest of its kind in Europe.

Archive film of Port Talbot steelmaking in 1964

1962: The Queen opens the £150m Spencer works in Newport, later known as Llanwern.

1967: British Steel is formed from 14 different firms as the industry is nationalised

1980: British Steel announces 6,500 job losses with the closure of blast furnaces at Shotton after 78 years. More heavy job losses at Port Talbot and Llanwern.

1988: British Steel is privatised and becomes part of Dutch-owned Corus in 1999.

1990: More than 1,100 jobs are lost at Brymbo steelworks in Wrexham.

2001: Corus announces 6,000 UK job losses - a fifth of its workforce. They include 1,340 at Llanwern in Newport, and 90 at Bryngwyn , externalin Swansea. The Shotton cold strip mill closes, external with 400 redundancies.

2002: The Ebbw Vale steelworks shuts with 850 job losses, external, although 300 workers move to other plants.

2007: Corus bought by Tata Steel of India

2014: Tata blames high business rates and "uncompetitive" energy costs for 400 job losses at Port Talbot.

2015: Tata Steel reported a "turbulent year" due to Chinese exports and high energy costs but Port Talbot produced an all time record of 4.19m tonnes of hot metal while the hot strip mill hit speed-of-work records.

In August, it mothballs part of its Llanwern plant for the third time in six years, with 250 job losses.

The Port Talbot blast furnace

What does it mean for the local community?

Ex-blast furnace worker Tony Taylor - who retired from the plant in 2015 after 44 years - is a local councillor.

"Port Talbot is the steelworks and the steelworks is Port Talbot," he said.

"If the worst happens to this plant it will blow a cold wind through the town that no-one has ever experienced. It will be a ghost town."

He said the effects would be felt beyond Port Talbot, with workers drawn from as far afield as Bridgend, Swansea and the surrounding valleys.

'Pride'

Swansea University historian Bleddyn Penny has studied the steelworks.

"After World War Two, there was a conglomerate of three steelworks in Port Talbot and it was the biggest in Europe," he said.

"Steel dominates the town economically and physically - you can't really escape it in Port Talbot. From around 1961, steelmaking was more important than coal mining in south Wales and it's defined the town.

"It's hard to think of other workplaces today with 4,000 under one roof. Despite all the pain and cutbacks of recent years, steelmaking is seeped into the whole culture of the town and there's a tremendous pride there."

- Published21 December 2015