How Wales Works: Measuring schools' success post devolution

- Published

In his book charting education policies in Wales since devolution, former education minister, Leighton Andrews says of the way policies were formed in the early years of the assembly, that it was:

"... suffering from a soggy consensus owing more to libertarian values of choice and prizes for all, than quality and standards. It was certainly a world away from the traditional pride, evident in valleys communities, about educational achievement... it also seemed a world away from the sharp focus on standards which Labour governments in London had introduced."

Scrapping school league tables in 2001 and SAT tests in 2004 were tangible changes in the early years, when the then education minister, Jane Davidson was still getting to grips with her new-found powers.

The idea was that teachers should be allowed to get on with the job of teaching without having to worry about tests and rankings in tables.

And yet, when he looked back to those days at the end of last 2012, current Education Minister Huw Lewis said: "I think there are questions that could be raised around taking our eye off the ball in the mid-2000s, around the basics in education, around literacy and numeracy. We've certainly put that right."

So what happened? What does Mr Lewis mean by "taking our eye off the ball"?

When Jane Davidson got rid of SATs, the plan was to replace them with a different set of tests, but that never happened.

Research from Bristol University, external claimed: "The abolition of school league tables had a negative impact on school performance in Wales, relative to England, by almost two GCSE grades per student per year on average."

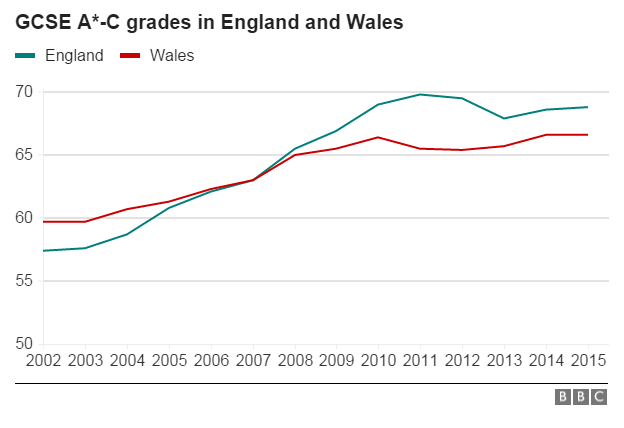

Comparing Wales with England in terms of GCSE results is problematic because England is, overall a wealthier country. However, as this graph shows, pupils here used to outperform their counterparts to the east.

If you look at the number of pupils gaining one A*-C grade at GCSE you will see Wales was ahead until 2006 when England catches up and then overtakes.

The real "game changer" for Wales' schools came after the disappointing international PISA tests, external in 2010.

In 2013 Wales was:

43rd in mathematics, down from 40th in 2010 and 34th in 2007

41st in reading compared to 38th in 2010 and 30th in 2007

36th in science compared with 30th in 2010 and 22nd in 2007

Leighton Andrews was the education minister at the time and said it should sound "alarm bells" for everyone involved with education in Wales.

As a result, many of the "made in Wales" initiatives were cast aside.

Whereas SAT tests were abolished in the early years of devolution, annual National Literacy and Numeracy Framework (LNF) tests were introduced in 2012 as a way of measuring how pupils were getting on.

After league tables went in 2001, school banding came in in 2013 to show how schools compare to others.

In short, the focus was very much on using data to drive up and ensure high standards - the complete opposite of the mantra of the early years.

I spoke about this with Prof Chris Taylor at Cardiff University a couple of years ago. He says there is a more accurate way of monitoring how our education system here compares with the rest of the UK, using what is called the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS).

The MCS is a study following the lives of about 19,000 children born in the UK in 2000-2001.

Prof Taylor says "they could be called the children of devolution".

"When we compare children in Wales with elsewhere in the UK, with very similar circumstances, from very similar backgrounds and similar households, they do slightly less well in their literacy test results, they do about the same in their numeracy tests. But they do better in other cognitive measures, which allows us to consider their other qualities," he said.

So there we have it, worse at reading, about the same in maths, and better at how our children are taught to think.

The funding of schools is another noticeable factor of education since devolution. Or, to put it bluntly, how much is spent on schools in Wales compared with England.

According to some reports, in 1999-2000, spend per pupil was £58 higher in England than in Wales; by 2009-10 the gap had grown to £604.

Teachers say the so-called "under-funding" of schools in Wales means they just cannot compete with a near-neighbour which spends so much more than we do.

Many educational experts, however, will tell you it is not how much you spend, it is how you spend it that counts.

The problem with trying to see how devolution has impacted on standards is that education policies take time to bed in and have an impact.

Many of the "flagship" policies the Welsh government introduced to improve standards only fully came into force in the last few years. So it could be a while until we see if they will lead to improvements.

- Published25 January 2016

- Published23 January 2016

- Published25 January 2016