David Lloyd George's WWI act 'helped save whiskey'

- Published

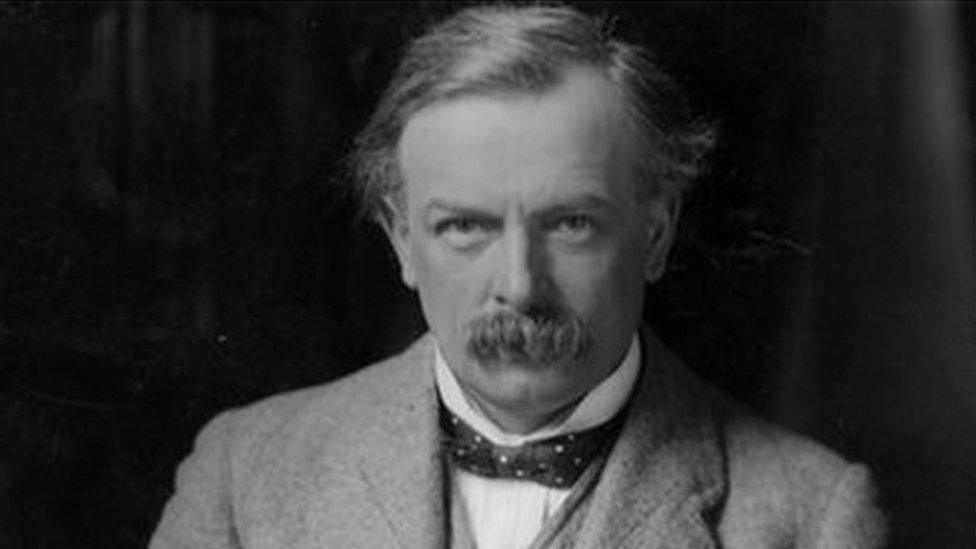

It was the act which teetotal politician David Lloyd George had hoped would put the UK whiskey industry out of business forever.

So he must have been confounded when the measure he thought would make the stills run dry actually turned out to be its saviour.

The Immature Spirits (Restriction) Act 1915 legislated for the first time that the alcohol must be matured in oak casks for a minimum of three years.

But as Jon Tregenna of The Penderyn Distillery explained, it helped "cement whiskey's reputation as a premium product".

As chancellor, Lloyd George's act represented an overdue - if not somewhat watered down - victory over the alcohol producers.

The MP for Caernarfon Boroughs had already been thwarted in several attempts to restrict the sale of booze, including total prohibition of alcohol throughout World War One.

Earlier that year in a speech in Bangor, he stated: "Drink is doing more damage in the war than all the German submarines put together."

According to Swansea University's WW1 expert Dr Gerry Oram, Lloyd George did indeed have a point.

"The context to this was the 'shell crisis' that followed the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915," he said.

"A promising British assault had floundered partly because each artillery piece used as many shells in one day as it took 17 days to produce.

"It led in part to the fall of Asquith's Liberal government, and in the new coalition administration, Lloyd George's ministry of munitions chief concern was increasing workers' productivity.

"The act was part of a wider range of legislation that took the state further down the interventionist route and attempted to raise taxation and limit the amount of drinking open to workers.

"The Licensing Act of the same year was the main one in this respect and introduced opening hours to create a break in the drinking day in the hope that workers would be more productive."

David Lloyd George thought alcohol was damaging the war effort

But as Mr Tregenna said, what Lloyd George actually succeeded in doing was help rescue the whiskey industry from itself.

"Almost all reputable whisky producers were already maturing their whiskey in oak barrels," he said.

"But prior to the act, whiskey had a terrible reputation because some producers were selling immature spirit straight from the still, which neither looked, smelt or tasted like proper whiskey.

"So whilst the legislation would have placed financial and logistical burdens on distilleries, it also helped to root out the rogues and cement whiskey's reputation as a premium product."

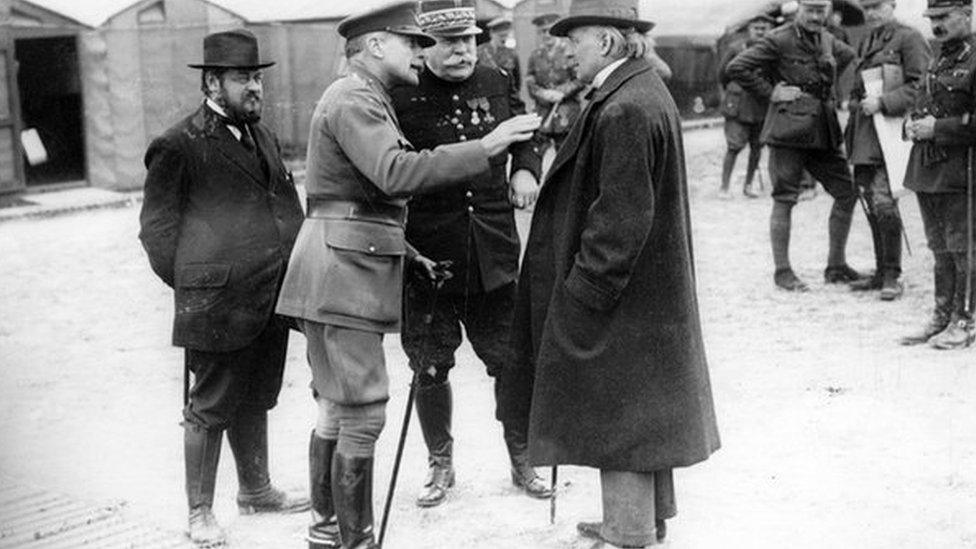

David Lloyd George with commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force, Sir Douglas Haig, whose family was in the whiskey business

Lloyd George's act did have its desired effect at first - of more than 130 Scotch whisky distilleries operating in 1914, only a handful made it through to the end of the war.

But as the reputation of the new, mature whiskies gradually spread, the industry enjoyed a revival in the inter-war years; in spite of prohibition in the US.

Today, whiskey exports generate £3.95bn for the UK economy and more than 10,000 people are directly employed in the industry.

So it is fair to say that Lloyd George's scheme did not go entirely to plan.

- Published8 August 2014

- Published13 June 2014