#towerlives: Rise of towers and fall of Tiger Bay

- Published

On Monday #towerlives kicks off, a week-long BBC festival of storytelling and music, on air and on the ground, in and around the council estate tower blocks of Butetown in Cardiff.

Its aim is to give a platform to voices from a community often talked about but rarely heard.

In the first of a series of stories from the tower blocks the BBC news website talks to one resident, who witnessed the extraordinary events that led to their construction, a history of fortunes - both financial and social - made and lost.

When the young Aristotle Onassis would sail in Cardiff's Tiger Bay, he always headed for one place.

Away from the high commerce and architectural splendour of the dockland's banking halls and buildings - a stately procession of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian-style magnificence befitting the world's coal metropolis - he would walk a short distance towards the legendary Bay.

The young Onassis, destined to amass the largest privately owned shipping fleet and beguile the 20th Century as one of its richest and most celebrated men, would turn into George Street.

There close to the bustling back-to-back terraces - a harmonious, cacophonous, cheek-by-jowl melting pot of 50-plus nationalities, faiths, costumes, food, music and customs - a Spanish immigrant who had settled in Tiger Bay ran a delicatessen.

Josefina Hormaechea prepared meals for the teenage Onassis, pictured with his new bride Jackie Kennedy in 1968

Onassis, then a humble teenage seaman, would walk under the rows of chorizo hanging from the rafters and make his way to a dining room upstairs.

There he would join five or six fellow Greeks some of whom lived in the area, among them Alexanderos Callinicos, a local ship chandler.

He was a friend of the shop's owner Josefina Hormaechea's and he would regularly ask her to prepare a meal - typically soup and roast lamb with potatoes - so the men could meet and discuss business.

Whenever, years later, Josefina was reminded of her encounters with Onassis and people would ask her what he was like, her daughter Gloria Del Gaudio remembers she would exclaim: "He was a skinny, ugly little kid."

To Josefina the man whose company the most glamorous and influential in the world would clamour for, was just another itinerant seamen washed ashore into Tiger Bay from the Seven Seas on an unrelenting, rhythmic human tide.

Photo taken between 1910 and 1915 of a gridlock of ships due to the coal strike

One of the four docks around 1900. The fifth the Alexandra Dock would be built seven years later

"Cardiff was like Saudi Arabia at the turn of the 20th Century," says Neil Sinclair, author, historian and the only genuine Cardiff accent to feature in J Lee Thompson's 1959 movie Tiger Bay, which starred John Mills and his daughter Hayley in her first starring role at the age of 12.

"But instead of oil it was the prized anthracite coal of the south Wales Valleys which was exported to the rest of the world.

"It had been transformed from an insignificant village in the middle of marshland to a city at the centre of everything. Coal, iron and steel industry from the south Wales valleys had ignited Britain's' industrial revolution."

The 'black gold' of the Rhondda created untold wealth. Cardiff docks made 'millionaires by the minute', its financial quarter second only to the Square Mile of London.

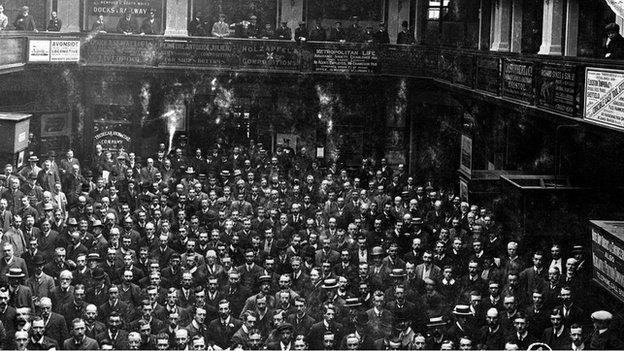

The thronging trading hall of the magnificent Coal Exchange, now largely derelict, set the price of coal worldwide and it was where the signing of the first million pound cheque took place.

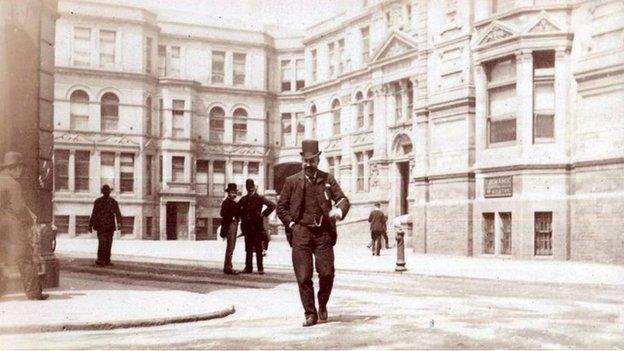

A businessman outside the Coal Exchange, now partly derelict but there are plans to turn it into an hotel

The trading floor of the Coal Exchange where the first million pound cheque was signed

And along with the financial prosperity came a societal richness.

The high demand for labour led to the creation of one of Britain's first and arguably most distinctive and successful multi-cultural communities.

"There was no place quite like it on earth," says Neil.

"No matter where you were from, colour, religion, ethnicity, it didn't matter. Everyone thrived as one big community.

"It was like walking into an Aladdin's Cave. It had the flavour of a Kasbah. At one time 57 different nationalities lived and worked in respectful harmony."

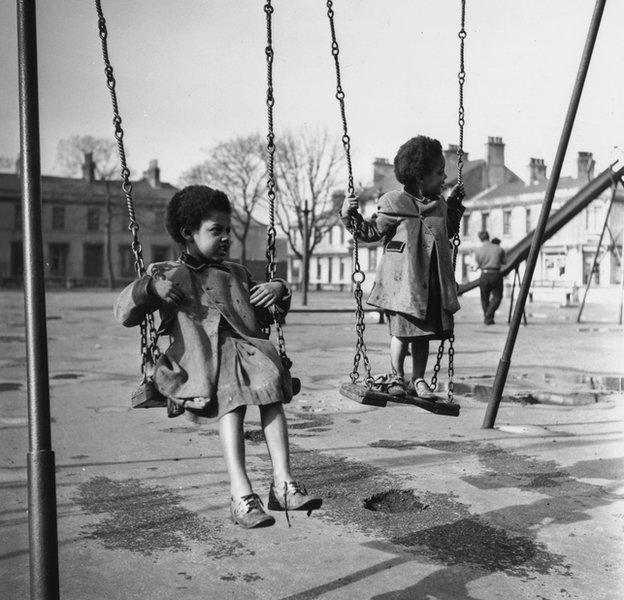

The acclaimed Welsh poet, writer and broadcaster Gwyn Thomas said of Tiger Bay during a visit in the 1950s: "Whenever any two children of different races play together, humanity grows an inch or two; another ancient fear, another mouldering prejudice is told to mind its manners and behave."

Children from Tiger Bay enjoying a drink at a day of tea and games sponsored by the Colonial Defence Association

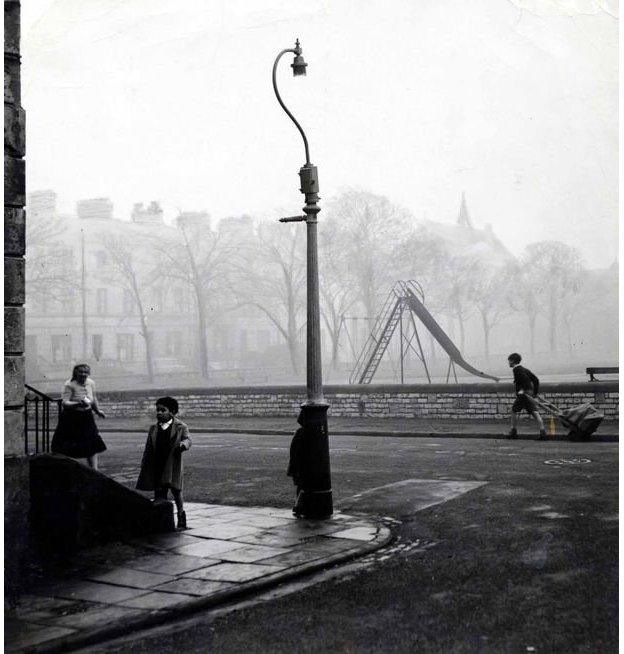

The recreational square which also included slides, swings and a large paddling pool

It is after all what we are famous for, so had the Welsh succeeded in teaching the world to sing in harmony?

"Tiger Bay was in the simplest words possible a symbol of racial, ethnic, religious and ecumenical harmony," says Neil.

"My mother used to say 'the League of Nations could learn a thing or two from Tiger Bay'."

Entertainment was largely found outside. While children were in the park, parents regularly pulled up a chair on the street and socialised

April 1950: Skimming stones along the Glamorganshire canal which was built to transport coal by the tonne from the south Wales valleys 30-or-so miles from the city

What a legacy for Cardiff; one to be cherished for generations to come you might think.

But get off the train at Cardiff Central today and ask for directions to Tiger Bay and you are likely to be met with a scratching of heads.

Just the other side of the railway track, almost every last vestige of the area has been wiped from the face of the earth; the fact it once existed let alone its staggering history largely unknown by many of those living in the city today.

But then that, some bitterly protest, was precisely the plan.

Fishmonger plying his trade on the streets where there was a shop, pub or cafe and invariably a dice game, on every corner

Tommy the fish: One of many street hawkers who did daily rounds of the 9,000-strong community

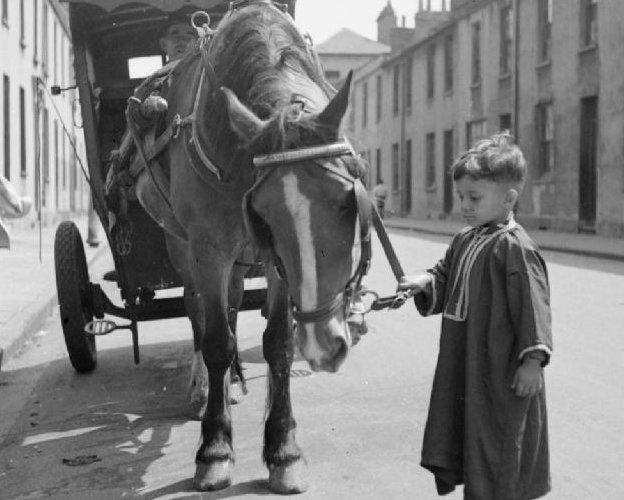

Hassan, a young Muslim boy, saying hello to the baker's horse on his rounds in Tiger Bay 1943

Cardiff, one of Europe's youngest capitals, is an emerging city on the UK map. A popular sporting, weekend and holiday destination it is prized for its vibrant nightlife, culture, shopping and gateway to outstanding rural and coastal wildernesses.

But as the ghosts of the past would attest, the 'Diff' as it is has become affectionately known is no 'new kid on the block'.

The city's re-discovered swagger was woven into its DNA generations ago.

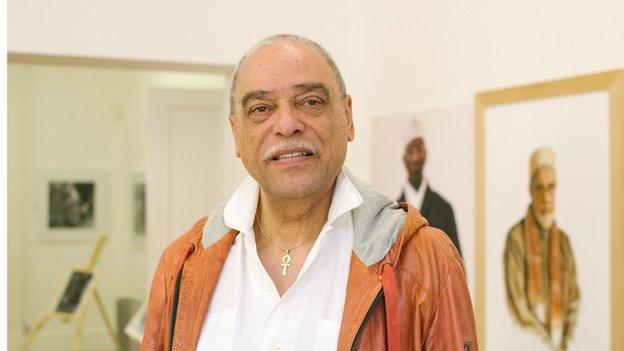

Neil Sinclair grew up in Tiger Bay. He still lives in the area in a high-rise council tower block of flats, built on the bulldozed rubble of his childhood home.

What happened to it was, he says, "one of the most torrid pages of meanness and spitefulness to be found in the annals of Welsh history".

The people of Tiger Bay face on the prospect of moving into high-rise flats

That history begins with John Crichton-Stuart, the 2nd Marquess of Bute.

A wealthy Scottish aristocrat, landowner and industrialist he realised vast wealth lay in the south Wales coalfields and set about exploiting it.

In 1839 the first in a series of docks was built - Bute West Dock, Bute East Dock, Roath Basin, Roath Dock followed and finally in 1907 the Queen Alexandra Dock.

Fine buildings sprung up and squares of decorative four-storey town houses were built around tranquil parks to accommodate magnates, merchants and sea captains.

Loudoun Square was chief among them and as the wealthy later began their migration to more verdant suburbs emerging in Cardiff, such as Cathedral Road, it become the beating heart of Tiger Bay.

Surrounding it were the terraces of Butetown which ran off the main artery of Bute Street and had been built as a model village in the early 19th Century for workers. Christina Street, Maria Street, Angelina Street, Sophia Street - addresses which remain today - were named after children in Crichton-Stuart's family.

The south side of old Loudoun Square, the Wesleyan Chapel seen on the left which was also demolished

The trees in Loudoun Square which were uprooted to make way for change in the 1960s

By the later 1800s Butetown had taken on its unofficial name as the legendary Tiger Bay, the source of tales once told by sailors around the world.

"Local folklore has it that there was a woman who used to walk around Loudoun Square with two tigers but then seamen were known for their tall tales," says Neil.

"Portuguese sailors are believed to have come up with the name. The tides in the area are notoriously difficult. After successfully docking they would say that sailing into Cardiff was like sailing through a bay of tigers. And so it was - Tiger Bay stuck."

Another theory is that its reputation as a wild hotbed of hedonism, rough house boozers, crime, prostitution and illegal gambling earned it sole use of a once generic term long used by sailors for raucous ports everywhere.

Some of the nicknames given to the area's 97 pubs - House of Blazes, Bucket of Blood, Snakepit - infamous for brawling sailors and prostitutes could add some weight to that.

Jitterbug: A dance at St Mary's School to raise funds for a local church originally featured in Picture Post 1950 as part of a photo essay by Bert Hardy

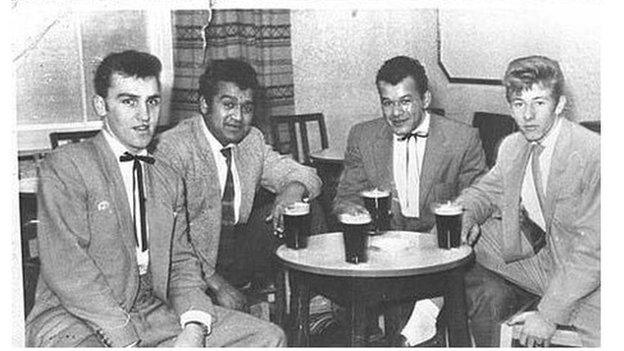

Pub life in the 1950s: Teddy boys tucking into a pint in one of the docks area's 97 pubs

It was a tough, hard life. No doubt about that. But many who grew up there would say that theory was just part of the conspiracy.

Other pubs were equally as well known for fantastic jazz and superb French cuisine, a magnet to out-of-town Bohemian types.

"This was a sea port and sea ports have had this sort of reputation for millennia," Neil says.

"If you have a Dickensian view of dockland life anywhere in the world you would cast aspersions on Tiger Bay. But that was purely an outsider's view.

"This was a major industrial port and thousands of workers descended upon it daily. Come 4 o'clock when the whistle blew they came out in what seemed like their millions.

"They got on their bikes but they didn't go home and slap the money on the table for their mams, they headed for the pubs and the place was jumping.

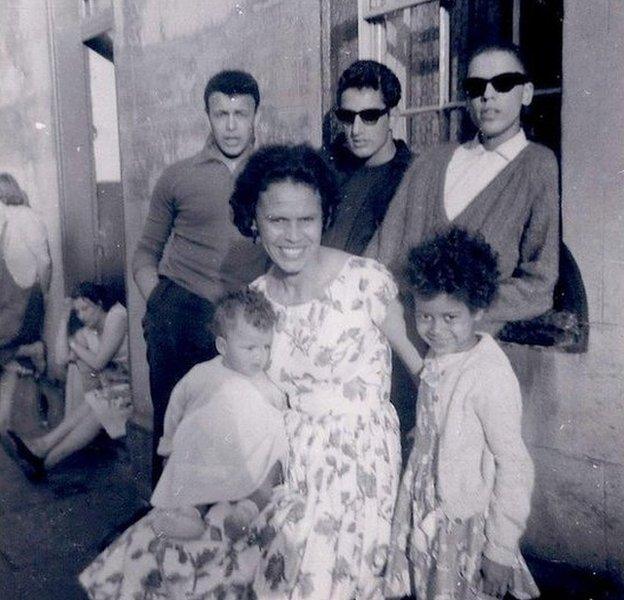

Neil (top right) insists the docks' reputation for crime and prostitution obscured the hard work and neighbourliness of those who lived there. Pictured with friends and sister Leslie and her children

Neil on Peel Street with Betty Campbell MBE (then Johnson) who went on to become Wales' first black head teacher and who remains a highly-regarded matriarch within the community

"And that's where your prostitutes come in. When the men were paid it was like moths to flames. But that's how the city of Cardiff gained its wealth, off the backs of those people.

"Yes, if you wanted trouble you could find trouble but that stigma obscures the fact that the majority of the men who lived there were hard working members of the community, not pimps running whores. Far from it.

"Everyone looked out for one another and nobody ever locked their door. If this was such a dreadful place then surely we'd have all been murdered in our beds?

"It was stigmatised. Good old fashioned racism. This was commonly stated on the streets of Tiger Bay - 'if you're black stand back, if you brown stick around, and if you're white, you're alright'.

Shirley Bassey, who sang in the local pubs and clubs, says goodbye to mother as she heads back to London after a weekend home

"The Victorian Imperial mentality was very much 'oh, what do black people do after dark?' They became the boogie man. Upper class families used to say to their kids who wouldn't go to bed 'I'll take you to Loudoun Square and leave you there!'."

By the beginning of the 20th Century the district had a burgeoning population of inter-racial married couples and their families.

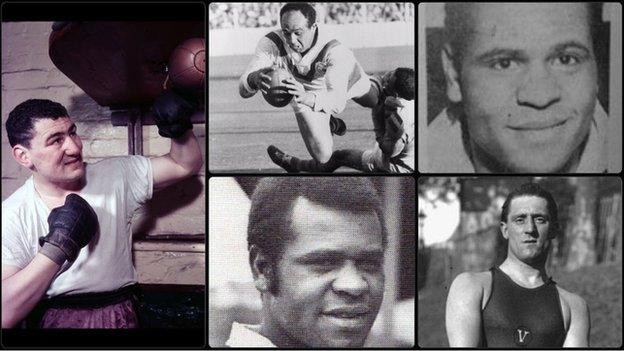

Among them Shirley Bassey, rugby legends Billy Boston MBE and Colin Dixon, heavyweight boxer Joe Erskine and swimmer and water polo Olympian Paolo Radmilovic, his father a Tiger Bay pub landlord from Croatia and his mother, the Cardiff-born daughter of Irish immigrants.

He won four gold medals across three successive Olympic Games, a team GB record only broken by Sir Steve Redgrave.

Clockwise from left: Joe Erskine (Getty Images); Billy Boston MBE (Getty Images); Johny Freeman; Paolo Radmilovic; Colin Dixon

Many of the local women who had married foreign men were commonly denounced as prostitutes who had shamed their chapel-going families by marrying 'heathens'.

"Part of the reason why multiculturalism worked was down to our Welsh mams and Welsh-speaking grandmothers," insists Neil.

"The sea men who were the heads of the family were more away at sea than they were at home. The white women in particular created a strong sisterhood, a Celtic matriarchy that kept us in line.

"Many of them came from the valleys and when it was discovered that they'd married an Arab or a Malay or an African, they were ostracised.

Mr and Mrs Thabeth's general store in the 1940s. Mrs Hassan feeding her baby son, Hamed. Also visible is the sigs above the counter which reads: "We do not give rations on Sundays."

The Satars: Abdul Satar (seated second from right) came to Cardiff from Aden at 16 and kept a lodging house. Left to right: daughter Meina Hodge, Allan Raffour (neighbour's child the family looked after since he was a baby), wife Emma Satar, Robert J Hodge (Meina's baby), Abdul Satar, and daughter Miriam Satar

'The Cairo', a popular cafe run by Ali Salaman, (in background doorway) and his wife, Olive from the Rhondda. They met when she was a nurse and made a wrong turning coming out of the cinema

"They couldn't go back home. So Tiger Bay became their home and they formed a strong alliance. We were one big family.

"Cardiff was a place people would head for. My grandfather docked in Bristol from Barbados. As a seaman of colour he was confronted with racism. But the word had got out 'if you want to feel at home, get to Tiger Bay'."

Others did not share the enthusiasm.

Around the time of the Great War as the docks was at its zenith, the self-proclaimed moral arbiters of the day made no secret of their loathing, and stories spread about "Cardiff girls sold into slavery every night".

Newspapers reported stories about policemen patrolling the streets armed with sabres and of grave concerns of a "great increase in alien floating population… earning high wages able to buy property for fancy prices and clear out British residents".

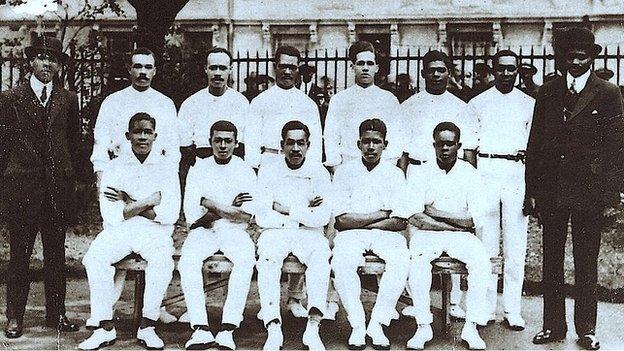

The Coloured International Cricket Team 1924: pictured in Loudoun Square. Danny Sinclair, Neil's grandfather (front row, centre) was captain

In truth seamen and dockers were poorly paid and their families led a hard life. And it was about to get even harder. Cardiff had enjoyed the boom, now it was time for the bust.

Oil was growing in importance as a maritime fuel and by 1932, in the depths of the depression, coal exports had plummeted.

Despite intense activity during the Second World War, exports continued to fall, ceasing altogether in 1964.

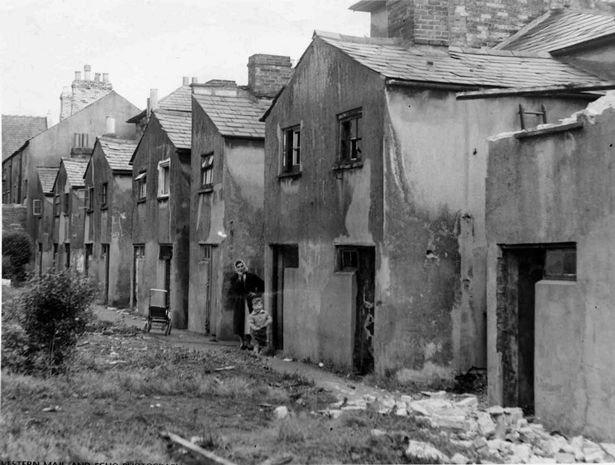

There was mass unemployment and parts of Tiger Bay's housing, which had no indoor toilets or bathrooms, had fallen further into dilapidation.

There was also a rise in tuberculosis and social deprivation.

In the early 1960s under the orders of the city's fathers, the bulldozers began moving in. Tiger Bay, along with all of the area's 97 pubs, bar one, the Packet, was razed.

Residents were moved to other areas of the city with the promise they could return to newly-built council homes. But after a period of a couple of years, many had settled and did not come back. The community had broken up.

A woman and child waiting to be evicted from the run down housing that is to be demolished

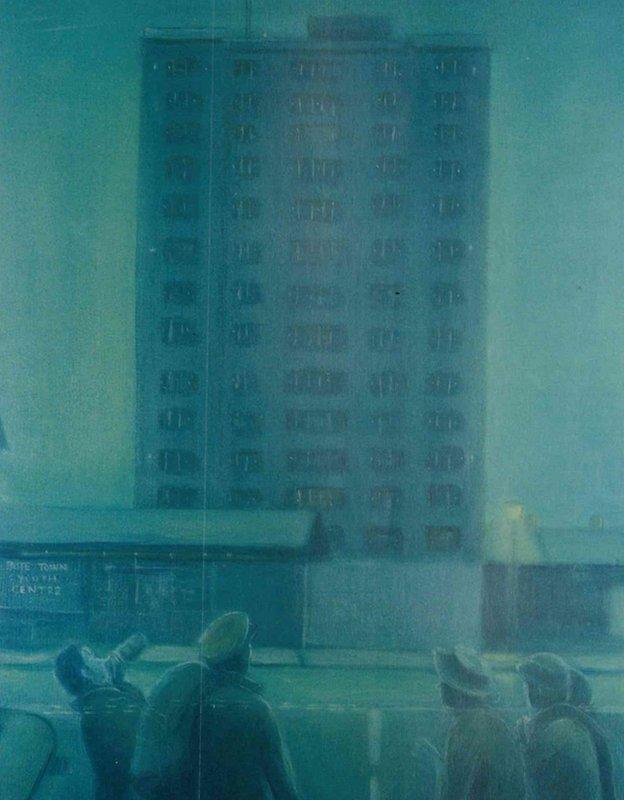

Tower blocks and low-rise flats take the place of the rows of terraced houses of old Tiger Bay

"They said it was a slum and all the lies you can imagine," Neil says.

"From an insider's perspective we were targeted, something to be got rid of.

"Rather than renovate housing in stages as they'd done in neighbouring Grangetown for instance, they wanted us gone and one way to do that was to knock it all down.

"All they succeeded in doing was destroying the architectural legacy of the Marquess of Bute for Cardiff and for Welsh history.

"Replace it with the first council estate to be dropped on to an inter-generational, multicultural, multiethnic, multiecumenical community. It was a tragedy.

"As a child you think the whole world is like your immediate environment. It was only as I got older that I realised the rest of the world didn't live as we did, they didn't have respect and tolerance for one another.

"If I'd known then that it was only ever going to be a moment in time, I'd have screamed blue murder. But you thought it was going to be this way for the rest of your life."

Childhood in Tiger Bay: Neil in a scene with Hayley Mills (top); with father Walter; mother Beatrice and Ruff the dog

Neil says when they witnessed the old trees being ripped from the park of Loudoun Square, they knew the game was up, a community which had grown over 150 years was gone.

"Loudoun Square was the jewel in the crown," he says.

"I've been in London wandering round and turn a corner and my heart drops because I see a square reminiscent of it and I think 'our Cardiff could've been so fabulous'.

"All those houses were solidly built. Some of the terraces had granite foundations. The wrecking balls were hitting the walls eight to nine times before they would give.

"If they were here today, they would be the houses tourists would flock to see. Instead we have a lacklustre council estate, an architectural monstrosity."

Neil, who has recently published his third book on the docks and Tiger Bay area, at the Butetown History and Arts Centre

In a BBC Wales interview in 1982 the then Lord Mayor of Cardiff Philip Dunleavy described the building of the tower blocks as "a disaster" and one which Cardiff would not repeat.

"They're anti-social," he said. "I don't know if you've been on to the top floors but it's like living in the country, one's very remote except for the corridor on which one lives.

"People tend to get lonely and the neighbourliness they experienced when they lived in terraced houses has disappeared."

By the early 1980s the once thriving docks was a neglected wasteland of dereliction and mudflats.

Its residents say they suffered from social exclusion, above average unemployment and social services which used their home as a "dumping ground" for problem cases.

The docklands had given the city its wealth but had then been disinherited.

The old and the new: The Pierhead building in front of Cardiff's Wales Millennium Centre in today's Cardiff Bay

In 1987 redevelopment plans were announced.

Its aim clearly stated: To put Cardiff on the international map as a superlative maritime city which will stand comparison with any such city in the world, thereby enhancing the image and economic well-being of Cardiff and Wales as a whole.

The irony was not lost on some. After all that description sounded painfully familiar.

In 1999 the construction of a controversial barrage was complete, built to impound the rivers Taff and the Ely to create a massive fresh-water lake. The area - now home to the Senedd, Dr Who studios, a sports village, restaurants, bars and the Wales Millennium Centre - was re-branded as Cardiff Bay.

Meanwhile, a stone's throw away in Butetown, the grievances persist.

Sweet Tiger Bay: A mother in pursuit of her child hanging out in a foggy Loudoun Square 'back in the day'

"The stigma's still there," says Neil. "That's the Cardiff mentality.

"Living in the towers is like living in a prison; cameras on every floor. That's not just my point of view. Many people will say the same thing.

"People of my age and older are walking around with a pain in the heart.

"I might go to sleep every night in the new Loudoun Square but when my head hits the pillow I'm back in the old Loudoun Square."

Neil wrote his book 'Endangered Tiger' in a bid to restore a sense of pride for Tiger Bay.

In it he cites a poem called Sweet Tiger Bay attributed only to 'M' which was published in the Western Mail on Saturday, August 23rd 1902.

Its final lines encapsulate the love and lament felt by so many, living and dead, for the magic and mayhem of the place:

I live in troubles, but they pass like bubbles,

When Fancy conjures up the days that were:

Put Death before me and an Angel o'er me,

To bear me upward-this to him I'd say:

"Young friend, your attitude has won my gratitude;

But please, another night in Tiger Bay!"

'Where's Tiger Bay gone shipmates?' Five ghosts return from sea but cannot get their bearings. By the late Cardiff artist and former docks policeman Jack Sullivan