#towerlives: Cardiff Three Tony Paris' freedom fight

- Published

#towerlives, a week-long BBC festival of storytelling and music, on air and on the ground, is under way in and around the council estate tower blocks of Butetown in Cardiff.

Its aim is to give a platform to voices from a community often talked about but rarely heard.

In the second of its stories from the tower blocks the BBC news website talks to Tony Paris who was living in one of them in 1988 when he was arrested for the brutal murder of Lynette White.

His subsequent conviction went on to become one of the UK's most infamous miscarriages of justice.

When Tony Paris went for a night out with a friend to the Dowlais club in Butetown on 8 December 1988, he had no reason to think it was the last he would ever fully enjoy.

In the early hours of the morning he left the club and walked home to Nelson House, one of two tower blocks of flats in the area's Loudoun Square. He got into the lift, pressed the button to the 7th floor and once inside, crashed out in bed.

At ten past seven that morning he awoke abruptly.

"I'm lying in bed and I hear this bang, bang, bang, bang, bang on the door," Tony says.

"I'm at the end of my bed naked thinking 'oh God, it's the boys'. I get up to open the door. Because I think it's the boys, I just flung it open for them to come in."

His friends were not on the other side of the door.

What happened next would alter the trajectory of Tony Paris' life and set in motion one of the UK's most infamous miscarriages of justice.

Speaking from his flat just a few miles from his former home in the docks area, Tony says: "Stephen King couldn't write a better horror story than this."

But this was not the first 'horror story' of this kind in Butetown's history.

On 3 September 1952, 28-year-old Mahmood Mattan, a Somali sailor and a father of three, was executed in Cardiff prison for murdering shopkeeper Lily Volpert, a crime he did not commit.

Mahmood Mattan (second right) Tiger Bay, 1950. His wife only found out he was dead when she went to visit him and found a death notice pinned to a door

He was the last man to be hanged in Wales.

There was no forensic evidence, the one witness at his trial had been paid to appear and even Mr Mattan's own defence barrister, his only hope, described him as a "semi-civilised savage".

His conviction was quashed 46 years after he went to the gallows protesting his innocence.

Tony Paris was about to endure a similarly nightmarish experience.

The hammering on his door that morning was the police.

"It was CID," Tony says.

"One of them jumps on me, pushes me up against the wall says to me 'are you Tony Paris?' I said yes. He then says 'we're arresting you on suspicion of murder'.

"It's funny how your mind works when you're under stress, it can go down a trillion different routes to come back with some kind of answer in a micro-second.

"I'm thinking 'What happened last night? Well, me and Herbie were in the Dowlais, there was no trouble, there was no nothing. What they talking about?'.

"So after my brain's gone round the block a couple of times in a matter of seconds and couldn't think of anything, I said to them 'who's dead?'. They said 'Lynette White'."

Lynette White had been killed 10 months before on Valentine's Day in an unoccupied flat above a bookmaker's in Butetown.

The man responsible for the murder of 20-year-old Lynette White in Butetown, remained at large for 15 years

The 20-year-old sex worker's body had been mutilated. Her throat had been cut so viciously her spine was exposed. She had been stabbed more than 50 times.

Tony like many in the docks community had known Lynette - his father used to drink with one of her uncles - and, like everyone else, he was shocked by her death.

The police had issued a photo fit of a tall, white man seen in the area at the time. But house-to-house inquiries, media appeals, and a Crimewatch reconstruction, had led to nothing.

"I said to the police 'Lynette White? You're having a laugh," he says.

"We better go down the police station and sort this out, this is rubbish'," says Tony, who, by his own admission, was "no angel" but whose worst conviction up until this point was for shoplifting.

"I get dressed and we go down Butetown Police Station. These coppers are flinging photographs at me of Lynette lying there in the morgue. I pushed them back and told them 'I don't want to look at them. Why are you making me see that? I don't want to remember that'.

"Those photos are in my head to the day I die. God, that was terrible."

Tony was one of five men arrested - Stephen Miller, Lynette's boyfriend, Yusuf Abdullahi and John and Ronnie Actie.

No forensic evidence linked the men to the crime scene but police told them two women said they heard screaming and had seen them hanging around the flat the night Lynette was killed.

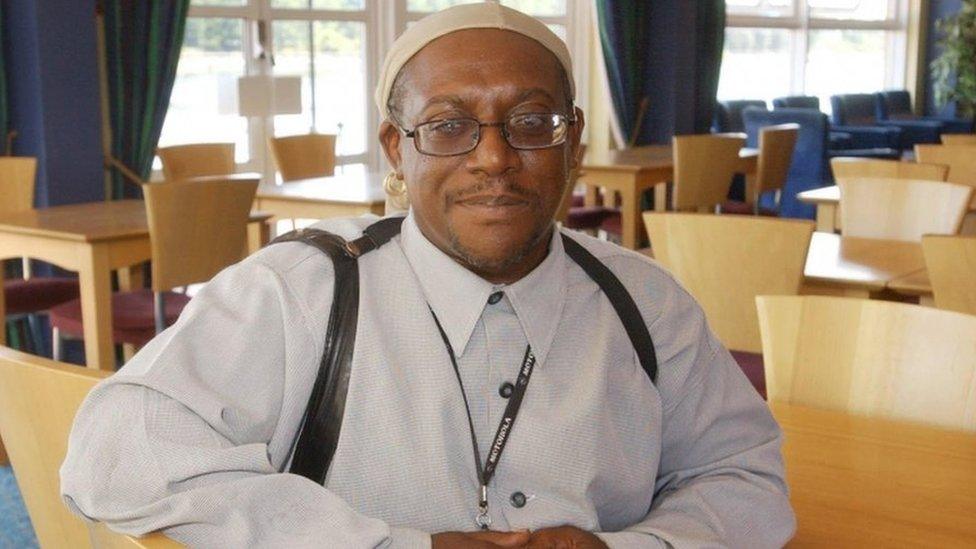

Tony Paris, who worked in the steel industry and as a club doorman, in a photograph taken a few years before he was arrested

Stephen Miller had also made a confession.

"The police broke him down so much that he ended up agreeing to their scenario," says Tony.

"He wasn't there. He knew nothing. But the police were messing with his head. And then it turns out he has the mental attitude of a 10 or 11 year old, but he can survive on the street.

"But he ended up after I don't know, 15 taped interviews, agreeing to what they were telling him. He's just agreeing 'yeah, yeah, yeah' to what they are telling him."

The five men stood trial at Swansea Crown Court in October 1989. After 82 days of evidence, a retrial was ordered following the death of the judge.

The second trial in May the following year was at the time the longest-running trial in UK legal history, lasting 197 days.

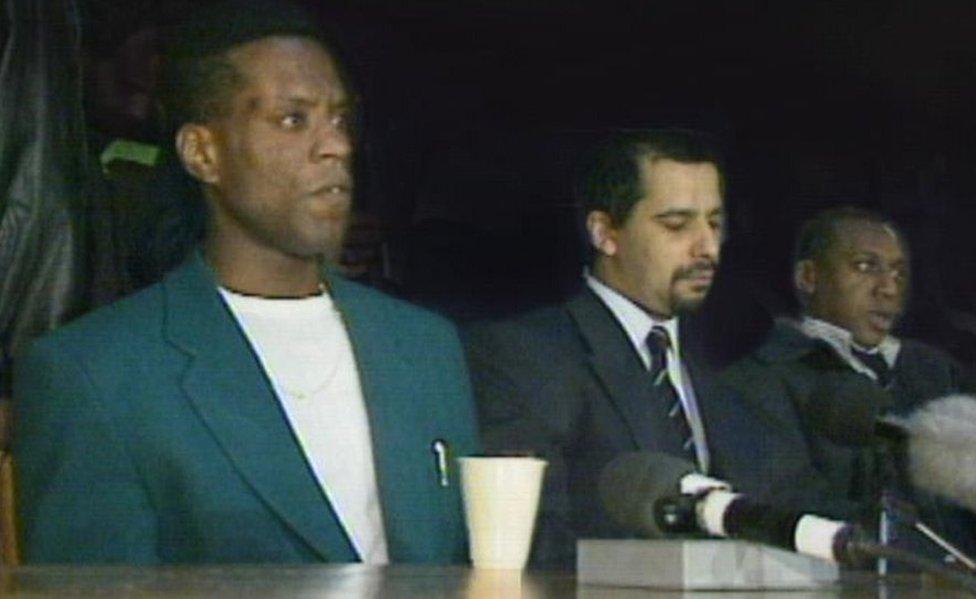

The Cardiff Three: Stephen Miller, Yusef Abdullahi who died in 2011, and Tony Paris

The jury heard evidence from a stream of witnesses who put the men at the scene of Lynette's murder.

Tony said there were so many contradictions in their evidence he was convinced no one was going to jail.

"You've got these two witnesses saying they heard screams coming from across the road at the bookies and then you hear their explanation for how they got across the road to the bookies," Tony says.

"One is saying they went down in the lift, the other is saying in her statement we didn't go down in the lift, we went down in the stairs… you know these girls are lying and they were never there in the first place. I thought I was going home."

The evidence may not have stacked up but Tony was not going home.

While cousins John and Ronnie Actie were acquitted, Tony, Mr Miller and Mr Abdullahi were sentenced to life imprisonment for murder.

"It's the worst thing you can ever imagine," he says.

In an interview with Jeremy Vine earlier this week on BBC Radio 2, Tony told him: "Emotionally, mentally there isn't words to explain certain types of feelings when things happen to you.

"So I'm telling the police for months 'I don't know nothing, I don't hang around with these people and indeed if you're telling me these people were there, they wasn't there with me'.

Al Sharpton came to Cardiff to speak at a campaign rally calling for justice for the Cardiff Three

"I don't know how many times; how many ways you're supposed to tell police officers you don't know nothing. Still you tell them, nobody's listening and you realise this is now very serious."

While serving his sentence in Wormwood Scrubs a campaign to prove the innocence of the 'Cardiff Three' became a cause celebre.

Among its supporters was Al Sharpton, the American civil rights leader, now a trusted adviser to Barack Obama.

In an address he gave in Cardiff at the time Mr Sharpton said: "I'm happy to be here to talk to you about the injustice that has happened to these three brothers. It is clear that it is only because of their socio-economic and racial status that they are in jail."

At lunchtime on 10 December 1992 after a four-day hearing at the Court of Appeal, the men's convictions were quashed.

Delivering his judgement Lord Chief Justice Taylor said of the police interrogation that led Mr Miller's confession "short of physical violence, it is hard to conceive of a more hostile and intimidating approach by officers to a suspect".

Tony Paris was a free man for the first time in four years.

But it was bittersweet.

Nelson House, one of two blocks of flats in Loudoun Square, where Tony lived on the 7th floor

Just weeks before his release, his father had died.

The pain of knowing he went to his grave without seeing his son vindicated and the belief that the strain of his plight contributed to his death will never ease.

"He was in his last stages and I went to Cardiff to see him with the screws," Tony says.

"They took the handcuffs off and went to the other end of the ward leaving me sat with my old man. My father was looking at me, looking at these strange guys then looking back at me."

"In prison I remember the priest came into my cell at five to 11. I looked at my watch. I knew my father had died. As soon as the key went in the door, I knew my father was dead."

Tony's life once out of jail was still over-shadowed by continuing suspicion.

"I was known as an extrovert, a club person, a night person," he says.

"I didn't want for nothing from life. I had everything. I was working, I could kick a football, I was married, had kids.

"When I came out of prison it was different. My boys wanted me to go out and I'd say 'no, I'm staying in'.

Tony having a swab taken by South Wales Police in a bid to end his link with the murder, just months before the real killer was arrested

"The damage had been done. My life had changed, trust and faith in people had gone, I didn't want to be around people on buses, trains, anywhere."

In March 2003 Tony was walking along the street when he got a phone call from a friend.

"One of the boys called me," he says.

"He said 'have you heard the radio? They got somebody for the murder'. I said who they got? Jeffrey Gafoor he said. I'd never heard of him."

Gafoor, then a 38-year-old security guard who worked nights but otherwise lived as a recluse in the village of Llanharan, a 30-minute drive from Cardiff.

"I met my friend and he gave me the newspaper," Tony says.

"I sat down and read it. I cried for the first time since all this started. Prior to that I couldn't cry especially in prison, you can't show emotion or weakness.

"Remember now, I'm black, I'm little and I'm Welsh in an English jail. Wasn't good, wasn't easy at all."

Gafoor had been arrested after police picked up his 14-year-old nephew for a misdemeanour.

They found his DNA was compatible with spots of blood found under layers of paint on skirting boards at the murder scene when the investigation was re-opened in 2000.

But the teenager could not be guilty. He had not even been born at the time of Lynette White's murder. Detectives asked him for details of his relatives.

Gafoor was convicted in July 2003.

A football mad young Tony whose family had settled in the Butetown - or Tiger Bay as it was then known - from Nevis St Kitts, pictured with his uncle

At his trial he said while he would never forget murdering Lynette White his memory of what happened was patchy.

He told the jury he could remember asking himself why he had "carried on killing her when I could have just left.

"I think I was very angry. I would be guessing if I said why."

And of the five innocent men who stood trial for a crime he committed?

Gafoor said he felt "terrible".

The witnesses who gave evidence against Tony at his trial were later convicted of perjury.

"The judge in their trial accepted the evidence they gave, that they were bullied to lie about us," Tony says.

"I don't know how you can be a police officer and deliberately make people lie about other people just to get a conviction and carry on your life with your wife and kids like you're doing the right thing."

Eight former officers, who strongly deny they acted improperly, were formally acquitted of perverting the course of justice when it emerged vital prosecution documents had been destroyed.

"A week or two later, the papers that were supposed to be destroyed were where they always were," says Tony. "In a room - 200 boxes, 200-odd boxes. It's just amazing."

Tony at home in Cardiff docks, an area he says has always been discriminated against by the rest of the city

"I can curse and swear," he says.

"Don't think I don't feel it, I just try to hold it down and be positive. I'm as full of resentment as anyone caught up in this but because of my upbringing, I know hate gets you nowhere.

"All it does is stress you out and makes you think stupid things. So what's the point? There's none is there?"

The community will always be his home, his parents having settled there from Nevis St Kitts not long before Tony's birth in 1957 when it was known as Tiger Bay, a multicultural district razed as part of a slum clearance in the 1960s.

"Living in the docks was brilliant," he says.

"I was brought up with all nationalities, all colours all religions. White boys, black boys, Somali boys Arab boys, Chinese boys, we didn't see that, we were just docks boys.

"We'd all leave the area to go to town together and if we found ourselves in a fight, we stick together."

That code of honour did not change when Tony was in jail.

He had got into one almighty fight and the docks stuck by him, doing all it could to help prove his innocence.

"They've always wanted to break us down, split us up," he says.

"There's this circle over Tiger Bay that will never disappear, never go away. That area will always be strong."