World War One: Wales footballers who never came home

- Published

About 20km (12.5 miles) south of Lens, where Wales play England in Euro 2016 is another foreign field, Arras.

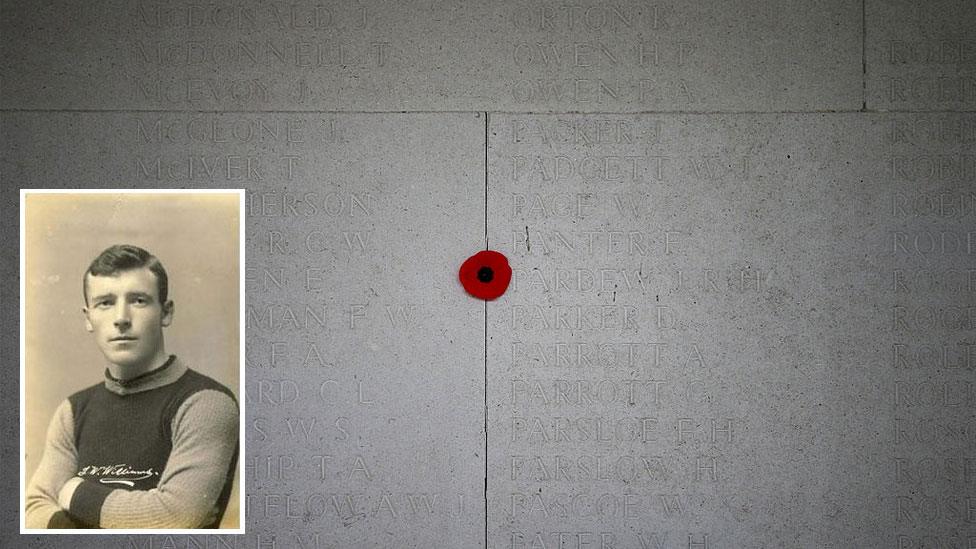

In the western part of the town in the Faubourg-d'Amiens cemetery is a memorial to the missing: 35,000 soldiers who were killed in the last two years of World War One. Their bodies were never found but their names are inscribed, row by row.

Among them is that of the Welsh footballer James "Ginger" Williams. A hundred years ago this month, he was blown up by an exploding mine, aged 30.

Williams was at his peak as a footballer when war intervened in 1914. But he soon found himself occupying a very different front line to the one he was familiar with on the football field.

The game has changed a lot since the early 1900s but Wales fans might be familiar with the narrative: Energetic, journeymen footballers from lower rung clubs giving their all for the red shirt alongside a sprinkling of more gifted stars.

Williams was one such unremarkable footballer. A stocky forward, he played alongside fellow north Walian, Billy Meredith - one of the superstars of the early 20th Century - to win his two caps.

While he was not of Manchester United star Meredith's quality, Williams, from Buckley, had proved more than useful. He scored 58 goals for Crystal Palace in the Southern League, mostly as an inside forward.

His attitude to the game was reflected in his nickname - "the Palace terrier".

Busy and tenacious, when switched to centre forward, he scored five goals in a game against Southend at Sydenham in 1909 causing "as much surprise as delight" for the 7,000 crowd. As one local newspaper described it "Williams had fine support and was in his element".

Williams transferred across south London to Millwall but had only a few months at his new club when war was declared.

He was in the right place to become one of the first to join what became known as the Footballers' Battalion - the 17th, Middlesex Regiment.

This particular "pals" battalion was set against a background of growing criticism that matches were still being played, while young men were going off to war.

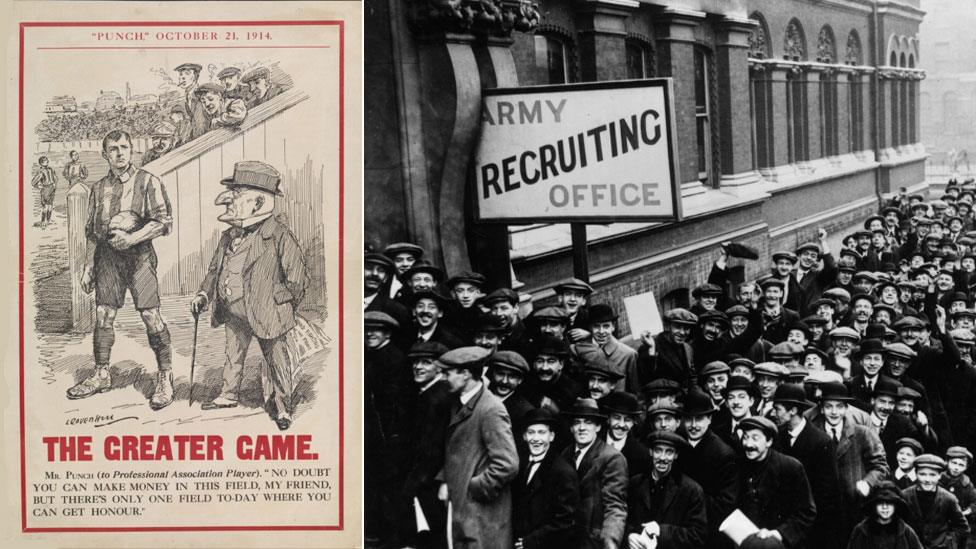

A cartoon encouraging footballers to join up, and queues at a London recruiting office in December 1914, when John Williams joined up

Within four days of the launch at Fulham town hall in December 1914, Williams had added his name.

Recruitment posters were soon being displayed outside stadiums encouraging supporters to follow the players in joining up.

More than 120 players alone would sign up with the battalion by the following spring, and while training for war at home were given Saturdays off to play for their clubs.

Other Welshmen to enlist included Cardiff City's Fred Keenor, just 20, who would suffer a gunshot wound to his thigh at the Somme in July 1916.

He was one of the lucky ones. Keenor got to go home and resume a career that would see him lift the FA Cup in 1927 - Welsh club football's greatest triumph - and win 32 Wales caps.

Cardiff team-mate Lyndon Sandoe, a full back in his early 20s, became company sergeant major.

His honours on the front line would eclipse anything he ever managed on a football pitch.

Sandoe was decorated three times for gallantry, including a distinguished conduct medal for "splendid coolness and fearlessness at all times under intense fire of every description".

The destruction in Arras in 1916

The ruins in Arras in June 1916, the month John Williams died

James Williams's service record notes that stocky frame: 5ft 5ins tall and with a 37in waist. Eleven months after enlisting, he shipped across to France, leaving a three month old son Kenneth with his wife Sarah in New Cross.

The Arras memorial with John Williams (inset)

It appears Williams was seconded to the Royal Engineers in the spring of 1916 and died on 5 June. His body was never recovered but his name is there at Arras.

Palace and Millwall staged a benefit match for his widow and son.

His name is also on a plaque remembering Millwall players who died in the war; his family had a large photograph of "John Will," as they called him, wearing one of his Welsh caps on the wall.

OTHER WELSH FOOTBALLERS WHO DIED IN WORLD WAR ONE

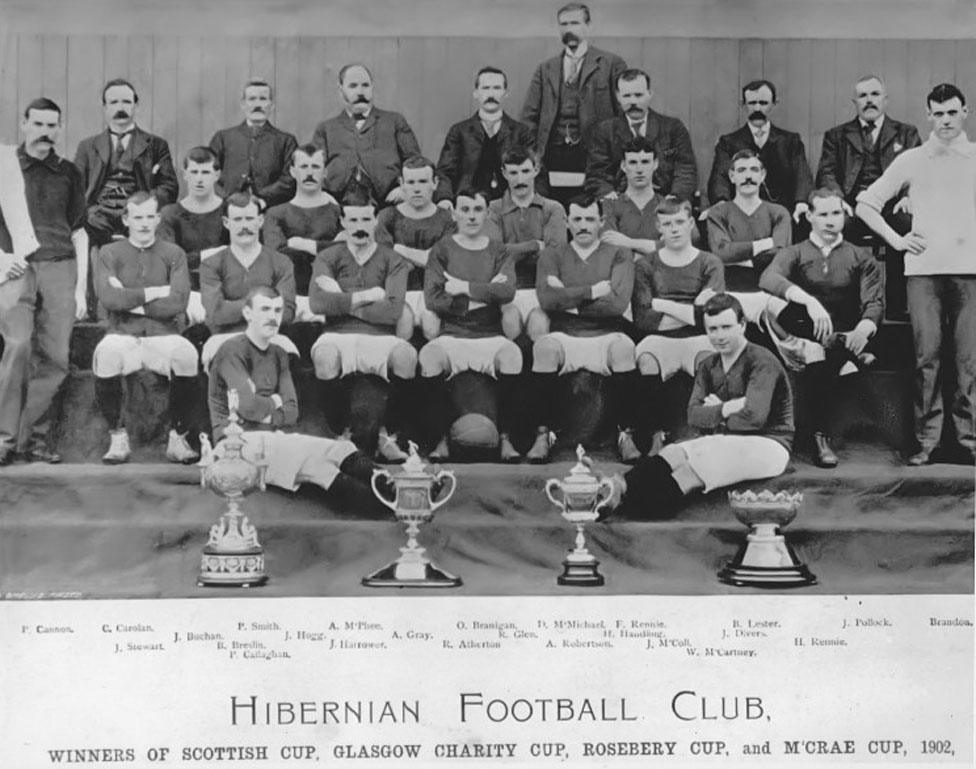

Bobby Atherton, captain of cup-winning Hibernian in 1902, in the front row centre with the ball. The feat was not repeated by the club until this year

Robert "Bobby" Atherton. Born Bethesda, Gwynedd; nine caps for Wales, died 19 October 1917, aged 41.

An inside right, his clubs included Hibernian - he was captain and memorably lifted the Scottish Cup in 1902 and also led them to the league title. Retired from playing, Atherton moved back to Edinburgh, where he joined the Merchant Navy as a steward. The SS Britannia carrying iron bound for France was sunk by U-Boat in the English Channel with the loss of 22 crew.

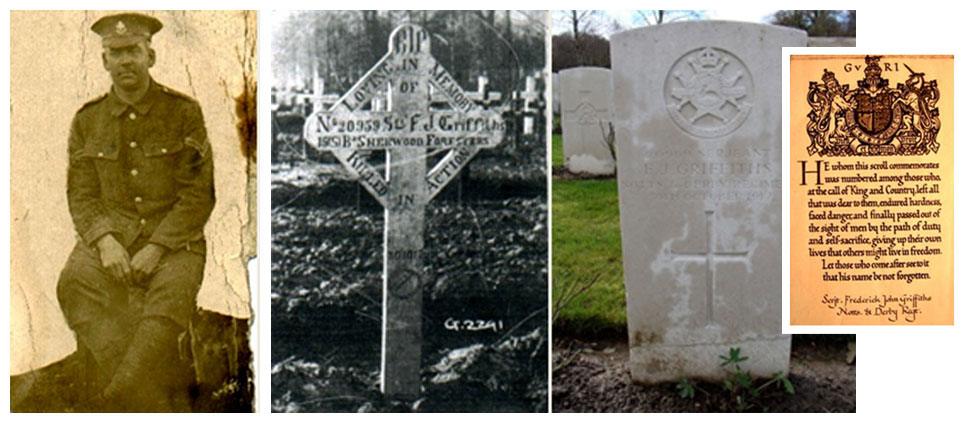

Goalkeeper Fred Griffiths was killed in Flanders in 1917

Frederick "Fred" John Griffiths. Born Presteigne, Powys; two caps for Wales. Killed 30 October 1917, aged 44.

A goalkeeper, he won both his Wales caps - against Scotland and England in 1900 - while playing for Blackpool. He went on to play for clubs including Preston and West Ham.

His great-grandson Stewart Woodland, who lives in Australia, has spent eight years researching Fred's story.

Fred was born in Harper Street in Presteigne, the son of a coal merchant and played for his local club and occasionally for Knighton.

Hs burly 6ft 2in, 15st physique saw him work part-time in the metal-working and blacksmithing industries before he launched himself into the world of professional football at the age of 21.

Stewart says Fred found himself playing for Tottenham Hotspur in an epic series of FA Cup ties against Southampton in 1901 but despite losing a second replay in a heavy snowstorm it was reported Fred's display was such he was carried "shoulder high" by supporters from the station afterwards.

Injury cut short his professional career at the age of 33 and he moved to Shirebrook in Derbyshire, where he helped train the local side. He also worked as a bar manager at the village's Station Hotel and by the outbreak of the war also had his own pork butchery business.

Fred Griffiths in uniform, his grave in Belgium and (inset) a memorial scroll

After joining up he rose to the rank of sergeant in the 15th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire (Sherwood Foresters) Regiment and was killed during the Battle of Passchendaele during the "big push".

Fred is buried in Dozinghem military cemetery, south of the village of Westvleteren in west Flanders, near the French frontier.

He left a widow Elizabeth and six children.

"The news of Fred's death caused general sorrow in Shirebrook, where 'Griff', as he was more intimately known, had a wide circle of friends," said Stewart.

Fred's granddaughter June Woodland has been to pay her respects.

"I feel so proud of him in all he achieved in his life and the ultimate sacrifice he gave," she said.

"It was such an emotional time when I went to visit his grave. I wish I had known him".

George Griffiths also served in the Royal Welch Fusiliers at some point before World War One

George Griffiths. Born Chirk, near Wrexham 1865; one cap for Wales; died 7 July 1918, aged 53.

Played for his local club Chirk - who were a strong amateur side, winning the Welsh Cup and producing 20 Welsh internationals around the turn of the 20th Century.

His granddaughter Barbara said George and his brother Peter both played for Chirk. "There is a story that they began playing football at school and were trained by the head teacher," she said. "He made them play with a plimsoll on their strongest foot in order to encourage them to use both feet!"

Griffiths worked as a miner before the war and had moved to Leigh in Lancashire, where he had eight children.

As inside left, he played for Wales once against Ireland in 1887, a 4-1 defeat.

A veteran of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, he was discharged from the Royal Army Service Corps in 1917 after an accident involving his knee - he already had signs of arthritis - and died at home in Leigh a year later. He may also have suffered from the effects of gas but there is nothing on his Army medical record and he died of stomach cancer. Nevertheless, he was given a military funeral.

William James Jones. Born Penrhiwceiber, near Aberdare; four caps; died 6 May 1918, aged 41.

Became the first player from the South Wales League to represent Wales in 1901, while a player with Aberdare Athletic. He also played briefly for West Ham, then a Southern League club. He joined the Royal Welch Fusiliers in Tonypandy and was killed in Macedonia - now northern Greece. His body was not recovered but he is remembered on a memorial there.

Roose in goal for Woolwich Arsenal five years before his death

Leigh Richard Roose. Born Holt, near Wrexham; 24 caps; died 7 October 1916.

One of the most flamboyant personalities of his era - Roose made headlines on and off the pitch as a goalkeeper for clubs from Wrexham, Stoke City to Aston Villa. This son of a pacifist minister always wore the shirt of his old university Aberystwyth under his jersey. Ambitions to become a doctor were diverted by football and a love of the London life. Girlfriends included music hall star Marie Lloyd and he wore Savile Row suits. Roose once hired a train at huge expense so he could get to an away match in Birmingham on time.

He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, and latterly the Royal Fusiliers, for whom he earned the Military Medal during his first engagement with them.

Roose's abilities as a goalkeeper to throw a ball it appears extended to grenades.

"Though nearly choked with fumes with his clothes burnt [he] refused to go to the dressing station," says the citation. "He continued to throw bombs until his arm gave out, and then, joining the covering party, used his rifle with great effect."

But just weeks later L/Cpl Roose was killed in the final stages of the first battle of the Somme at Gueudecourt, one of 190 dead or missing that day.

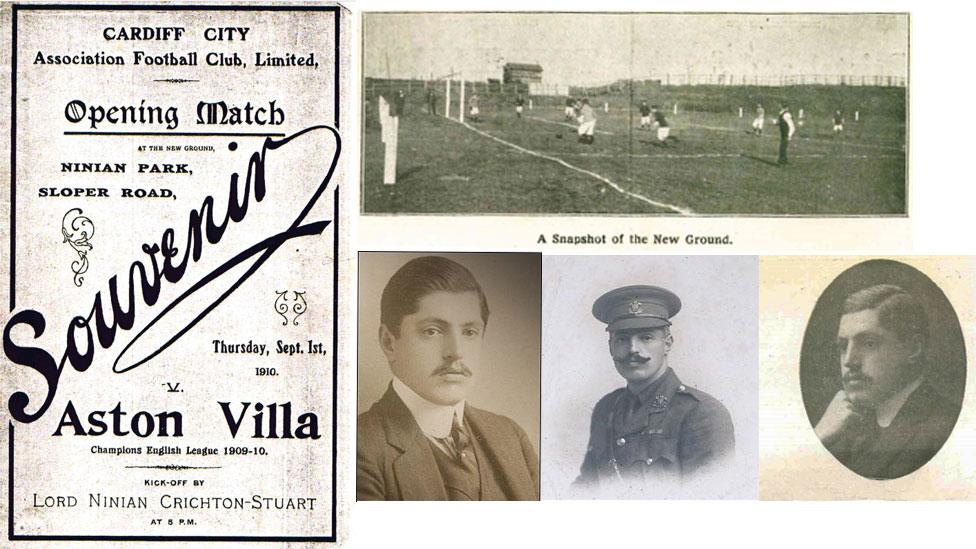

Lord Ninian Crichton Stuart (in the bowler hat with the cigarette)

About 10 miles north of Lens, is another Welsh football connection with the war.

Although not a footballer, Lord Ninian Crichton Stuart at least had a claim to fame in that he was the first to kick a ball at Cardiff City's stadium in 1910.

The second son of the third Marquess of Bute had stood as a guarantor for £90 so Cardiff City could rent their new ground from the local authority.

He was an important figure in helping the then Riverside club move to grander surroundings and turn semi-professional.

Club historian Richard Shepherd said: "The club had agreed a lease with the corporation but had to find a number of benefactors - and these had to be in place for the start of the 1910/11 season," he said.

"One of the benefactors withdrew at the last minute and Lord Ninian offered to fill the gap. He was particularly well known in Cardiff and added a lot of credibility to the club."

Ninian Park was subsequently named after him and he was invited to ceremoniously kick off Cardiff's opening match with Aston Villa.

Ninian - also a Cardiff Conservative MP - was already commanding officer of the 6th Glamorgan Welch Regiment and when war was declared, more than 840 men and officers - mostly from Swansea and Neath - volunteered and headed for France under him as Lieutenant Colonel.

At the Battle of Loos at the start of October 1915, after a decision to evacuate when ammunition ran out near La Bassée, Ninian was shot dead as he stood on the fire step to rally his men.

He was 32. Even after his death, his bequests helped the club.

Although Cardiff City now has a new stadium nearby, his contribution was such that one of the stands is named after him and the Ninian gates moved across the road.

Soldiers enjoying a game of football in 1915

Some of the 35,000 names at Arras of men whose bodies were never recovered

A memorial at Longueval to the footballers' battalion

Around 2,000 of Britain's footballers are estimated to have served in the war, while the Footballers' Battalion alone lost 900 men.

Some clubs suffered deeply. Heart of Midlothian in Edinburgh lost seven members of their first team. But Clapton Orient, who as a club provided an astonishing 41 players and staff, could be considered fortunate to lose only three at the Somme.

Of the Welsh internationals who died, only a couple were household names and all but John "Ginger" Williams had already retired from the game.

But those Wales supporters, who were gathering in Arras before the match, might care to imagine the rubble of the town a century ago and just a short distance away, where former heroes played their part and paid the ultimate price.

- Published15 June 2016

- Published10 June 2016

- Published11 June 2016