Mametz Wood: The stretcher bearers to the Somme's stricken

- Published

A ferocious Red Dragon, in full fight mode, its claws tearing at barbed wire, glares down at the ground and the wood where so much Welsh blood was spilled in a single week in July 100 years ago this week.

Much has been written about the strategies, failures, arguments and mistakes which resulted in the death of just over 600 men, with a further 600 missing and 2,800 wounded.

The stories of the heroic 16th Welsh (Cardiff Pals) and the 11th South Wales Borderers (2nd Gwent) Battalions who suffered badly in the first stage of the attack on 7 and 8 July and the 13th Welsh (2nd Rhonddas), 14th Welsh (Swansea Pals) and 16th Royal Welsh Fusiliers who fronted the second phase on 10 July, with the 14th Royal Welsh Fusiliers and 10th Welsh (1st Rhonddas) in support, have been told and retold.

One story which has never been told until now, is the story of the extraordinarily brave and unstinting, unarmed men who strove with every sinew of their strength and every ounce of their wit to bring the wounded home at Mametz Wood.

The Welsh dragon statue is dedicated to the memory of some 4,000 men of the 38th (Welsh) Division who were killed or injured in the battle of the Somme

The 38th Division had three Field Ambulance units, all raised in Wales towards the end of 1914 and early 1915.

One of these, raised almost entirely from St John Ambulance men working in the South Wales coalfields, is worthy of special mention.

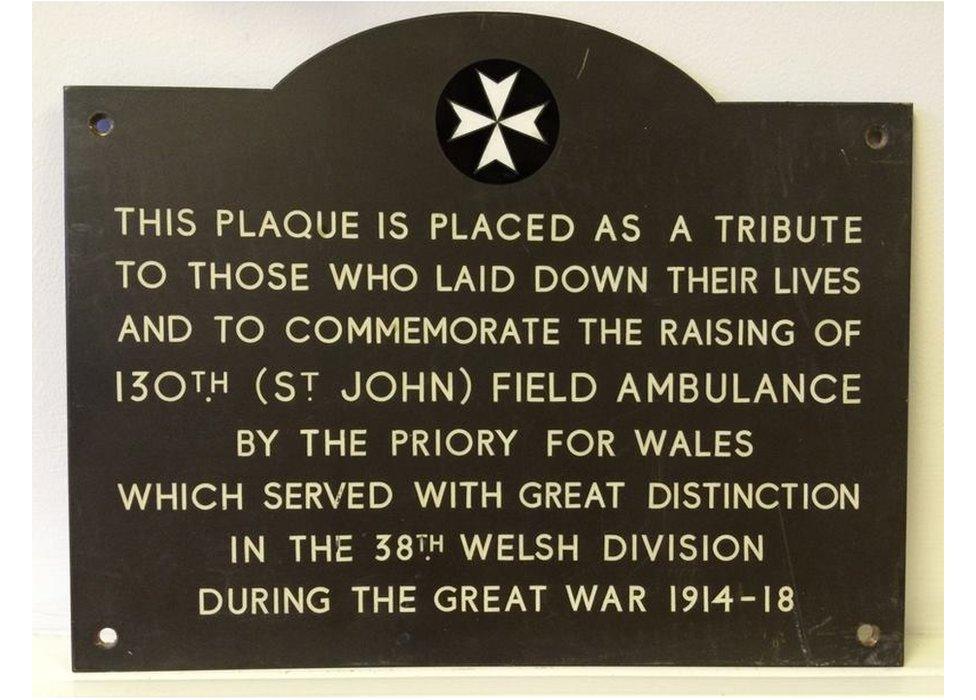

The 130th (St John) Field Ambulance was the only unit in World War One allowed to use the title "St John" in its name and to wear the St John eight pointed cross insignia on its uniforms.

Battle for Mametz Wood explained

It was this band of rather special brothers who found themselves at the forefront of one of the most difficult challenges of their lives.

As with all battles there was a plan for the rescue and evacuation of men from the battlefield.

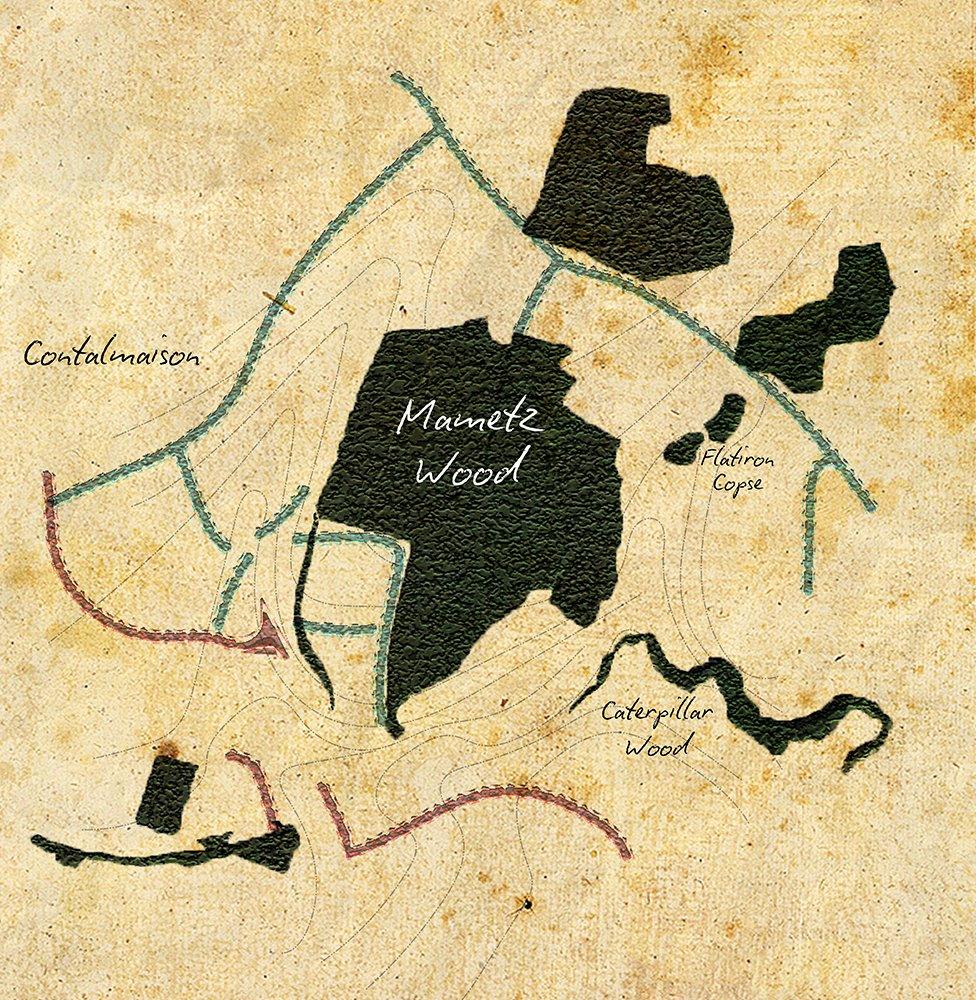

There were two routes, one to the south west via Mametz Village and another from Caterpillar Wood, via Caterpillar Trench and Triangle Aid Post, both converging at Minden Post Dressing Station, almost three miles south of the wood.

Men and Ginger the dog, their mascot, preparing for a route march during training in Prestatyn, north Wales, in 1915 before heading to France

From Minden Post the wounded would be taken by small gauge railway to Citadel Aid Post: Stretchers on trolleys drawn by mules and horses.

Those who survived at Citadel were taken south to the Divisional Collecting Station near Bray-sur-Somme and, from there, by horse-drawn and motorised ambulances to the Main Dressing Station at Morlancourt Church where the 130th were to attend to the 'light wounded', a total journey of more than 10 miles.

At 06:00 BST on 7 July, four officers and 100 bearers made their way from Morlancourt to Citadel with rations and wheeled stretchers.

Oliver Young's experiences at the battle of Mametz Wood

They found the Citadel dugout flooded and they were up to their knees in mud.

Leaving a handful of men under Medical Officer Captain Page to make sense of the mess, the remainder pushed on to the Triangle Advanced Dressing Station, one-and-a-half miles to the South of the wood.

As the battle got under way the bulk of casualties were found to be on the right flank of the rescue plan: the route which involved Caterpillar Wood and Caterpillar Trench, a former German communication trench which was narrow and boggy with mud.

The men were "in" (as they called it) for 16 hours that day.

At times it would take hours to cover just a small distance in the trench because of the mud.

The narrowness, mud and presence of soldiers going up the trench to the battle made it impossible to bring stretcher cases down.

There was only one answer: The men would have to go over the top.

Shells bursting all around them and now in direct sight of the German machine gunners, without flinching the men took their chances in the open, utterly aware that the delay could kill their cases as much as the enemy fire might.

The first 130th casualty that day was William John West from Cwmcarn.

A shell exploding nearby took his head off and injured William Jones and Sergeant Hill.

At daylight on 8 July the men buried West in a hollow at the bottom of the trench.

Training conditions: Men training in Prestatyn, north Wales, before their duty in France

Battle conditions: Troops help get an ambulance through the mud at Mametz Wood, July 1916

The situation was so dire that reinforcements had to be sent for from the other two field ambulances.

Casualties were being dressed and held in small dugouts along the edge of Caterpillar Wood and efforts recommenced to get these men down the trench.

Again, they had to go over the top and, this time, a sniper took William Houston. Houston was dressed and the men began to carry him down the trench but he died soon after.

Houston was buried in a shell hole at the side of the trench with shells exploding all around: large numbers of soldiers were filling up the trench and now many of them had been hit and needed attention.

The entire area was a mess.

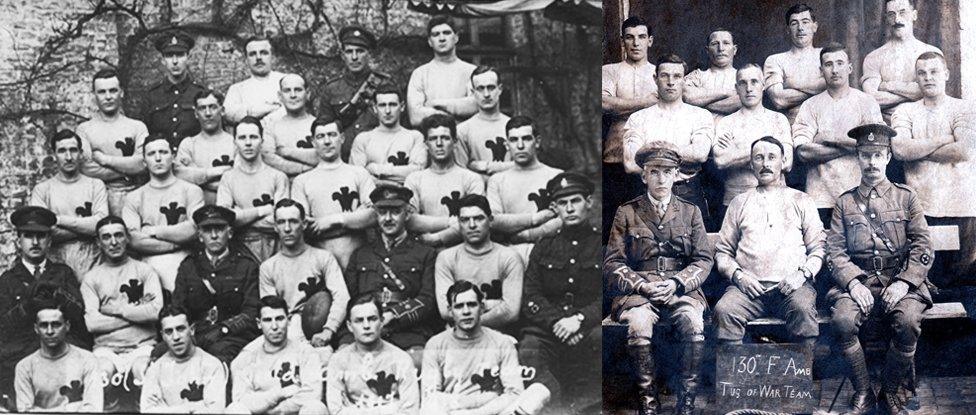

As the men endured horrendous experiences at the Somme, they found comfort in recreating some normality with sport - a rugby team and tug of war team

The villages of Mametz and Fricourt were nothing more than piles of smashed bricks, the ground was pitted with shell holes full of mud and blood-stained water.

There were still many German dead lying about from the previous push towards the wood and the stench was awful.

The plan for the second phase of the battle was that the 129th Field Ambulance would cover the left flank and the 130th the right.

The 131st were once more manning Minden Post.

The men were in position at Triangle Aid Post by 03:00 on the morning of 10 July.

From Triangle, bearer units were dispatched to the various Regimental Aid Posts of the attacking battalions.

The first casualties came into Triangle at 05:00 that morning and continued to come down by the hundreds during the day.

Within three hours there simply weren't enough bearers to cope with the casualties and cases were building up at Triangle.

The 130th opened another aid post at Pommiers Redoubt, the battle HQ, and a request was sent to the 131st Field Ambulance at Minden Post for more bearers.

The unit was raised mainly from St John-trained men from across the south Wales coalfields – Amman, Garw, Ogmore Vale and Rhondda valleys and Gwent

In error, the message went all the way back to Morlancourt Church, where even men of the 130th who had been up all night with the wounded volunteered and 31 men were taken by truck and ambulance to Minden Post and then on to Triangle.

Another aid post was opened at the village of Carnoy to cope with the numbers and during the afternoon bearers from the Sanitary section, the 142nd Field Ambulance and even the 130th's Army Service Corps drivers came to help carry the wounded from Triangle.

Captains Page and Anderson tended to the wounded at Triangle non-stop for 12 hours; it was 17:00 before they had a short break for a tin of tea and some bread and cheese.

Three times as many casualties were admitted to Minden Post on 10 July as had been over the whole of the three preceding days - 1,246 officers and men - and there was constant movement all through the night.

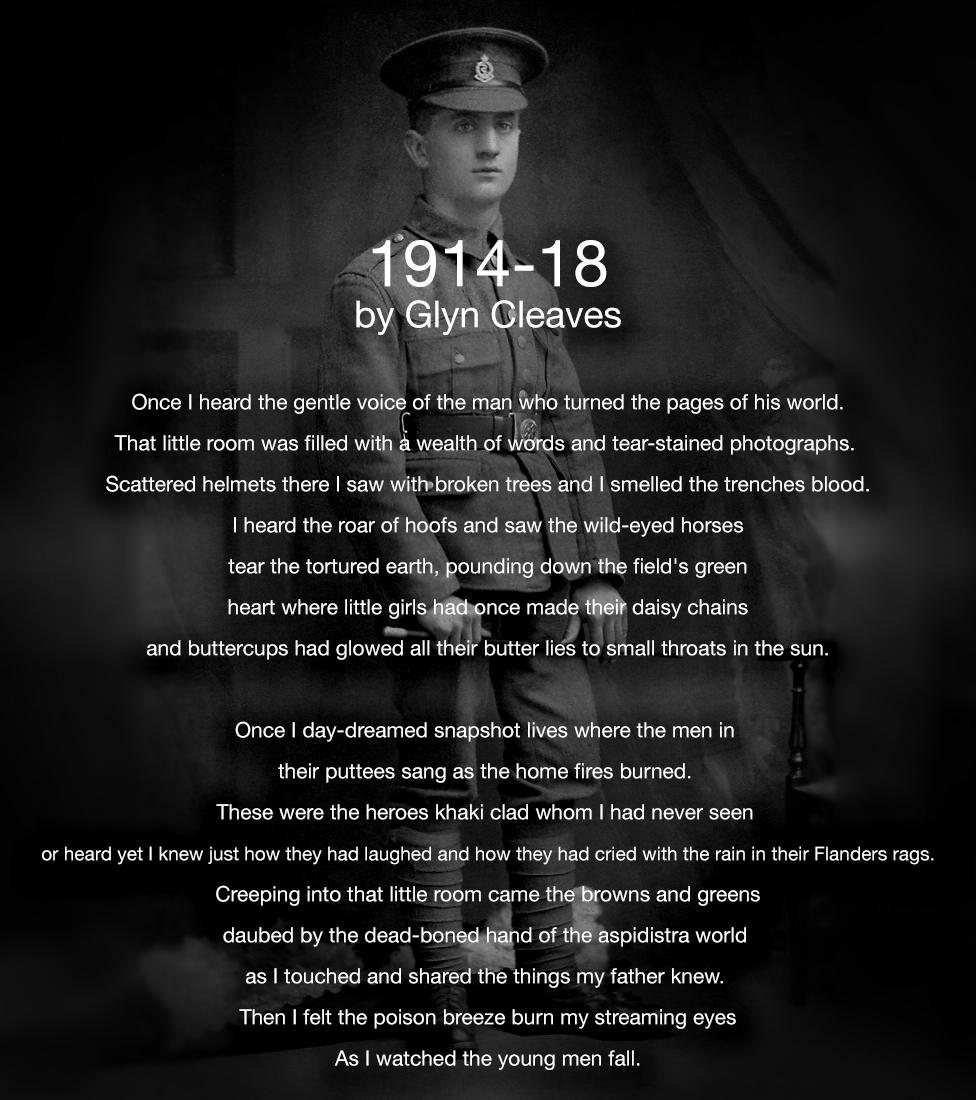

A poem written in honour of Private James Cleaves (pictured) from Abersychan, by his late son, Glyn.

On the morning of 11 July a request was again sent to the 131st Field Ambulance for more bearers but none were available.

The bearers of the 130th had to keep going right up until 17:00 that day: a total of 38 hours on the trot.

When Captain Page was relieved at Triangle at 21:00 on 12 July he had been on duty for three whole days and nights and on his feet for most of that time.

On the nights of both 10 and 11 July a unit of 100 cavalry men was guided by bearers of the 130th to collect the stretcher cases from the edge of Caterpillar Wood under cover of darkness.

Almost 1,000 men were admitted to Minden Post on 12 July.

Throughout all this mayhem, those casualties who had survived the battle and had found their way back to Morlancourt were arriving to be treated at the Main Dressing Station - sitting cases only being looked after by the 130th in the church and stretcher cases by the 21st Field Ambulance, also at Morlancourt.

It was a pitiful sight - blood-stained men covered in mud shuffling in with one hope among them, that they were wounded just enough to get a ticket home to "Blighty".

Some were cheery and some in tears.

In 2015 a plaque to Welsh ambulance men who won gallantry medals was re-dedicated at a service at St John the Baptist Church in Cardiff city centre

Leaving their packs and giving their names at one door of the church, they would go up the left aisle and sit until it was their turn to be dressed.

They would then shuffle back down the right aisle, be given coffee or beef tea, something to eat and a smoke.

They would then fall asleep in all sorts of positions or, if the weather was fair, they would stretch out on the grass and the tombstones to rest.

From midday on 10 July to midday on 12 July, more than 900 men were dressed at the Church, 620 of them in less than a 24-hour period.

It is difficult to imagine that any other group of men would have acquitted themselves with such devotion to duty, other than this band of serving St John Ambulance men, attested into the Royal Army Medical Corps and sent to face a most daunting challenge with unstinting courage and tenacity.

They repeated this devotion to duty in 1917 at Pilkem Ridge, during the 3rd Battle of Ypres.

The 130th (St John) Field Ambulance was an unique body of men in terms of both Welsh military history and the history of St John in Wales.