Mametz Wood: The Welsh attack and its legacy

- Published

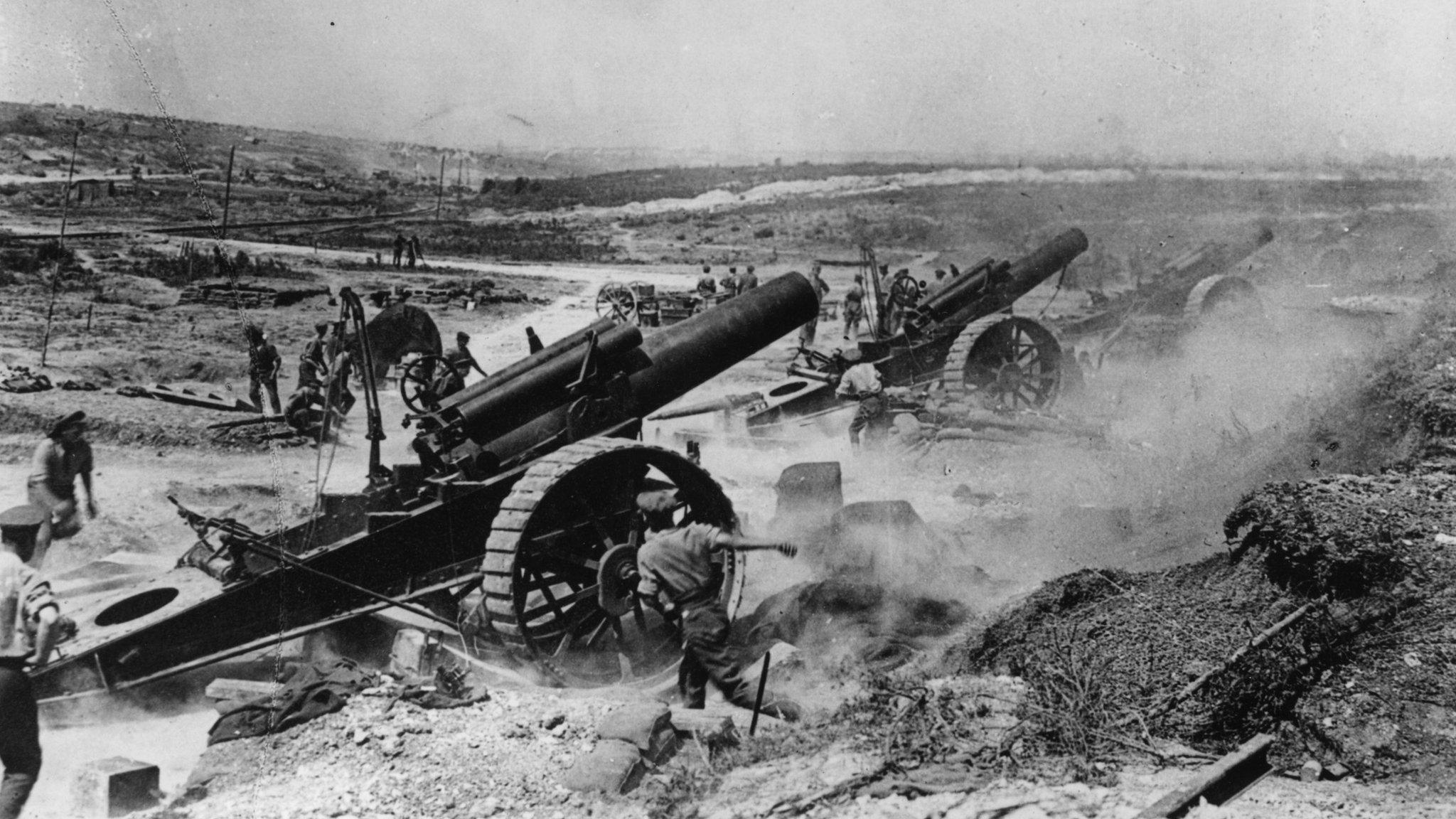

The 39th Siege Battery artillery in action in the Fricourt-Mametz Valley.

The 38th (Welsh) Division suffered heavy losses while driving German forces out of Mametz Wood as part of the Battle of the Somme. Prof Chris Williams of Cardiff University discusses the attack and its legacy.

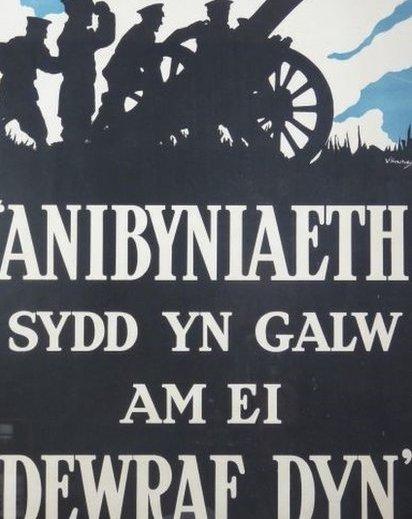

When the First World War began in 1914 the British army numbered fewer than 750,000 men.

Realising this would be inadequate for a war against Germany, a call for volunteers was issued and within two months more than 760,000 men had come forward.

Many volunteers were organised in 'pals' battalions of men from the same area, such as the 16th (Cardiff City) Battalion of the Welsh Regiment and the 11th (2nd Gwents) Battalion of the South Wales Borderers.

1st World War recruitment poster

One volunteer for the 2nd Gwent was my great-grandfather, William John Rogers of Pontnewydd, Monmouthshire.

Some 20,000 Welsh volunteers were brought together in the 38th (Welsh) Division, which sailed for France late in 1915 and went into the trenches in January 1916.

Ideally the 38th, along with other so-called 'New Army' divisions, would not have been used in a major offensive until 1917.

However, the German attack on the French at Verdun forced Commander in Chief of British forces Gen Sir Douglas Haig to launch an assault on German lines to relieve pressure on Britain's ally.

This attack, the Battle of the Somme, began on 1 July 1916. Overall, the first day of the Somme was a disaster: British troops suffered more than 57,000 casualties and in many places took no ground.

But in the south, advances were made, and the villages of Mametz, Montauban and (on 2 July) Fricourt were taken.

It became possible for the generals to plan an attack on the second line of German defences, but first they had to take Mametz Wood.

Mametz Wood now

Mametz Wood was large, overgrown and defended by experienced German troops.

The first attack, on 7 July 1916, failed to reach the wood. Welsh soldiers, who were expected to make a frontal assault in daylight on German positions, were machine-gunned as they moved across open fields.

'Impossible task'

A smoke screen that might have concealed their approach failed to appear and heavy casualties were suffered.

There was no lack of courage on the troops; they had been set an impossible task.

Maj Gen Sir Ivor Philipps, in command of 38th (Welsh) Division, was sacked on 9 July and replaced by the more experienced Maj Gen H. E. Watts.

Another assault on the wood was planned for 10 July.

This time the attack was launched at dawn and was preceded by a heavy artillery barrage of German positions.

The attackers still had to cross hundreds of yards of open ground in the teeth of machine gun and rifle fire.

More than one million people were killed or wounded during The Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest of World War One

Many men were cut down, but Welsh troops forced their way into the wood, where they outnumbered the German defenders by three-to-one.

Wood fighting was brutal, much of it involving hand-to-hand combat, and German resistance was fierce. The plan of attack had envisaged the wood being taken by 08:15 on 10 July - in fact it took until 12 July for the enemy to withdraw completely.

The Welsh troops had not been trained for this kind of warfare. Once in the wood, visibility was restricted and it was difficult to keep one's bearings.

Only officers carried compasses and very many of them became casualties leading the attacks.

Artillery support, initially planned to move forwards 50 yards every minute, was difficult to coordinate with the actual advance of men on the ground.

Communications wires were quickly cut and messages back to the guns had to be carried by runners, many of whom were killed.

Christopher Williams (1873-1934), The Welsh Division at Mametz Wood, 1916

Artillery fire frequently fell short, or shells burst early when hitting treetops, causing casualties among the troops they were meant to be helping.

The attack of 7 July had been hindered by heavy rain which turned the ground into sticky mud. Now the weather was hot (reaching 82 degrees Fahrenheit) and there was not enough fresh water to go around.

More Welsh troops were thrown in to the wood to support the first wave of the assault. Towards evening, the northern edge of the wood was reached in places, but the Germans were still holding on and threatening counter-attacks.

Bitter fighting continued throughout 11 July. The Germans suffered heavy casualties themselves and eventually decided to withdraw.

By dawn on 12 July, Mametz Wood had been taken and the 38th (Welsh) Division was relieved and taken out of the front line.

Overall, the division suffered severe casualties: One-fifth of its total strength on the eve of the battle. Of these, 565 were killed, 585 reported as missing (most of whom would have been killed, although a few were captured) and 2,893 were wounded.

The record of the 38th (Welsh) Division was controversial at the time. Rumours circulated of Welsh troops bolting and panicking.

One military historian, writing in 1919, argued that the failure to take Mametz Wood swiftly gave the Germans the opportunity to reorganise their defences, ensuring the Somme battle would be prolonged well into the autumn and its objectives only partially achieved.

Such views are today largely discredited. It is true that Maj Gen Sir Ivor Philipps was out of his depth and his dismissal as divisional commander was justified. But more junior officers performed commendably.

Given their limited training, their lack of combat experience and the difficulty of the challenge they faced, the dogged determination of the men of the division was impressive.

Already an artist, experience of war turned David Jones into a poet

The military historian William Philpott has called Mametz Wood a "gruesome baptism of fire" for the Welsh Division, crediting it for taking "a formidable position in one of the most intense close-quarter fights of the war".

The Battle of Mametz Wood has left an enduring legacy.

Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves and Frank Richards - some of the most famous of the writers produced by the war - even if they did not fight in the battle itself, were close enough before, during or after July 1916 to comment on what they saw.

Wyn Griffith, a staff officer serving with the 38th (Welsh) Division, whose brother Watcyn was killed during the battle, wrote a vivid and searing memoir Up To Mametz (1931).

David Jones, a private soldier serving with 15th (London Welsh) Royal Welsh Fusiliers, wounded in the fighting in the wood, placed his experiences at the heart of his epic poem In Parenthesis (1937).

Artists also found in the battle both inspiration and terrible fascination.

Christopher Williams's uncompromising depiction of close-quarter combat The Welsh Division at the Battle of Mametz Wood was commissioned by David Lloyd George shortly after the battle.

National Museum Cardiff is currently staging an exhibition, War's Hell: The Battle of Mametz Wood in Art, which brings together some of the most vivid imagery and testimony about the battle.

The Welsh memorial at Mametz Wood which was funded by public contributions

I first visited Mametz Wood more than 20 years ago.

Standing next to sculptor David Petersen's defiant dragon memorial, staring across at the edge of the wood, I decided to trace my great-grandfather's story.

He fought there. He survived. He died before I was born.

Apparently he rarely said anything about his wartime experiences.

Now, 100 years after the battle, it is right to remember him and to remember his comrades in the 38th (Welsh) Division.

And it is also right to remember - in David Jones's words in In Parenthesis - "the enemy front-fighters who shared our pains against whom we found ourselves by misadventure".