Wales and the Spanish Civil War - then and now

- Published

On the 80th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil War, Dr Hywel Francis looks back at the Welsh volunteers who went to fight for the Spanish Republic.

Dr Francis is the author of Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War (2012). He was Labour MP for Aberavon until 2015.

''How do I get to Spain?" These were the evocative words of unemployed Rhondda miner Harry Dobson on his release from Swansea prison, having served a sentence for leading an anti-fascist disturbance in Tonypandy in June 1936.

The fight against fascism in Spain, between 1936 and 1939, drew young men and women from all over Europe to form a rag-tag army.

Mr Dobson was one of 33 Welshmen, external to be killed serving with the International Brigades which fought to save the doomed democratically elected Spanish Republic government.

This Welsh solidarity was often referred to at the time as taking the form of an anti-fascist barricade stretching from Tonypandy to Madrid.

But why did they go and why was the response in Wales distinct, indeed unique?

Some today might think, in the context of political and cultural devolution, that the Welsh solidarity stemmed from recognising the national rights of Catalonia and the Basque Country which were, it has to be acknowledged, a factor in the Civil War.

Harry Dobson was killed at the battle of Ebro River in July 1938, just over a year after he arrived in Spain

On the contrary, the prevailing concern in both Spain and Wales was the rising tide of fascism across Europe.

Spain had provided the first successful resistance to this hitherto unrelenting surge, while in south Wales the mid-1930s was characterised by the greatest resistance in Britain to the policies of mass unemployment and appeasement of the national and Conservative governments.

The military rising on 16 and 17 July 1936 against the democratically elected Popular Front Republican government led immediately to the Spanish Civil War.

The response in Wales was largely provided by the South Wales Miners' Federation and the Communist Party and eventually supported by a broad coalition including the Labour Party, Liberals, some Welsh writers, academics and teachers.

One of the first to recognise the growing threat of fascism was Labour MP Aneurin Bevan who, as early as 1933, formed an anti-fascist workers militia - the Tredegar Workers' Freedom Group.

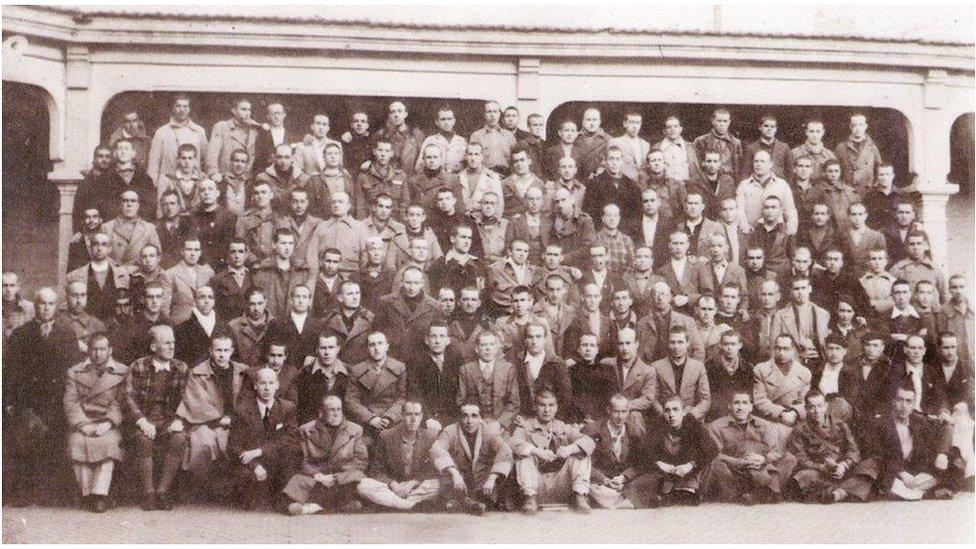

Welsh Volunteers of the XV International Brigade before the Ebro offensive, 1938

The 200-or-so Welsh men who volunteered to fight in Spain represented the largest regional industrial grouping within the British Battalion of the International Brigades; only one Welshman fought for the fascist forces led by General Franco.

They were Communist or Labour in sympathy, largely from the central valleys of the Rhondda, Cynon and Taff although there were also volunteers from the north Wales coalfield, the coastal towns of the south and rural areas.

Some became famous in later life as trade union leaders, notably Will Paynter and Tom Jones, known subsequently as Twm Sbaen throughout the labour movement.

They were immortalised in song by the Manic Street Preachers in their 1998 album This Is Our Truth, Tell Me Yours in which they quote the words of Bedlinog volunteer, Tom Thomas - "If I can shoot rabbits, I can shoot fascists".

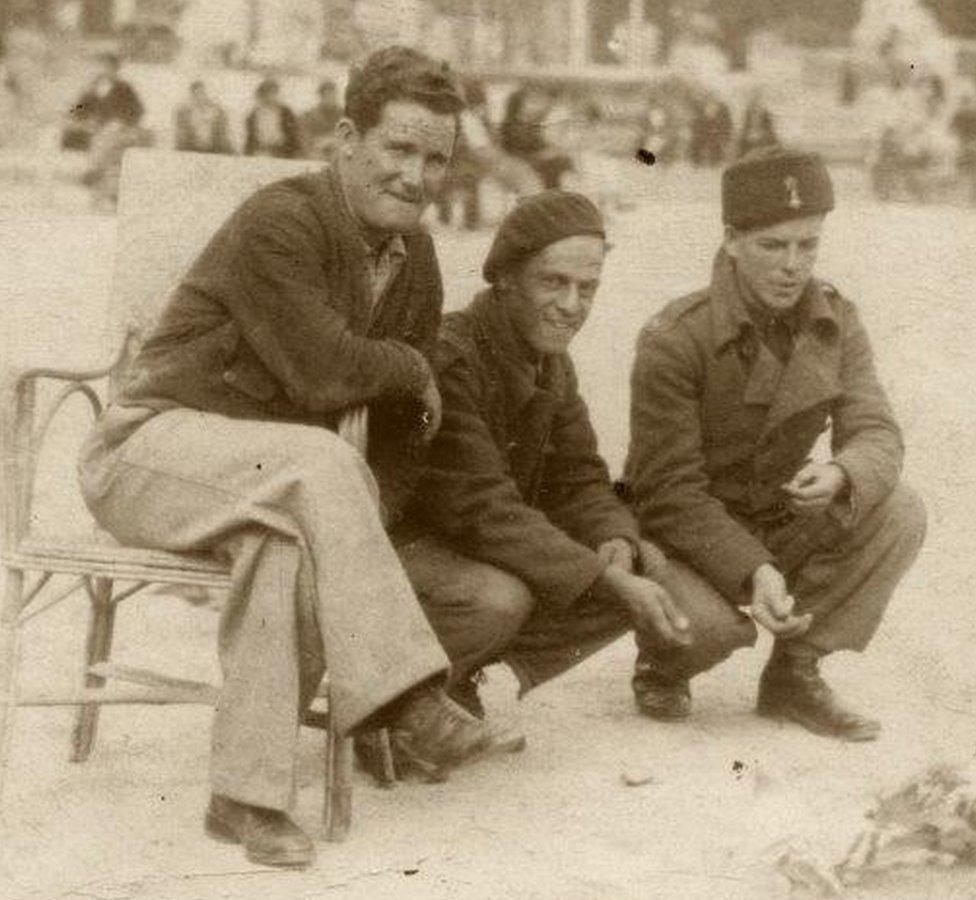

Tom Jones, aka Twm Sbaen, photographed in Barcelona 1938 with members of the anti-tank crews

They were immortalised too by the black political activist and singer Paul Robeson who spoke at their Memorial Meeting in Mountain Ash in 1938 when he memorably said: "...these fellows fought not only for Spain but for me and the whole world".

For the most part, these men were hardened "class warriors", having had at least a decade of bitter industrial and political experience after the General Strike of 1926, with stay-in strikes, hunger marches, leading mass demonstrations against means test regulations and halting fascist incursions into the valleys.

Following the bombing of Guernica on 26 April 1937 and the subsequent fall of the Basque Country, support in Wales broadened from the mainly working class Spanish Aid communities to the wider, more humanitarian Basque Children's Refugee Communities, with the prominent support of former Prime Minister David Lloyd George and his daughter Lady Megan Lloyd George, and also from leading academics, teachers and writers such as Gwyn Thomas.

They established four Basque Children's Homes in Colwyn Bay, Brechfa, Swansea and Caerleon.

The Basque children were the largest ever single influx of refugees into Britain. The government reluctantly allowed them to enter the country; by contrast, the British people and notably the Welsh people, welcomed them enthusiastically. A lesson, indeed, for our own times.

Tom Jones in Burgos penitentiary, 1940 (eighth from left second row) photographed shortly before his release - his death sentence commuted to 30 years and a day

The general response in Wales, unlike in England, was, however, not characterised by any great intellectual awakening.

An exception was Lewis Jones, the communist leader of the Rhondda unemployed, whose novels Cwmardy (1937) and We Live (1939) convey in vivid terms the political consciousness of the time.

The latter novel concluded evocatively with the Welsh miners' response to the Spanish republican cause.

The leader of the Welsh Nationalist Party Saunders Lewis was at best ambivalent towards the rise of fascism; it is said that he proposed a toast in a private dinner: "To a fine Christian gentleman, General Franco!"

Nevertheless other nationalists were forthright in their support of the Republican Spain and did so by writing in such magazines as Heddiw.

In more recent times the celebrated film-maker and poet John Ormond produced a five-part account of the Welsh miners in Spain in his award winning The Colliers Crusade (1981).

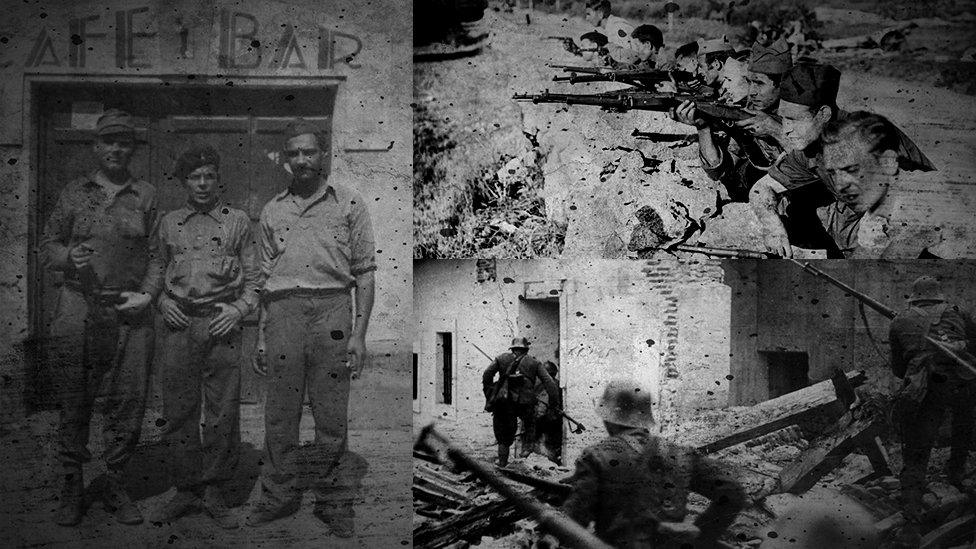

Nationalist troops loyal to General Franco advance through the debris of houses in Madrid wrecked in air raids

Memorials have been established in towns and villages all over Wales including the official International Brigades Association (Cymru) memorial at the South Wales Miners' Library, made of Welsh coal, slate and steel and unveiled by Will Paynter in 1976.

Some in the south Wales valleys still connect to these radical and courageous times.

My own father, Dai Francis, was secretary of the Onllwyn Spanish Aid Committee.

The distinguished Welsh actor Richard Harrington is very proud of his grandfather, the Merthyr volunteer Tim Harrington.

This fine sense of international political and humanitarian solidarity has now given way to nostalgia and even a mean-spirited parochial victim culture and should be subject of open and honest public debate in these sobering post-referendum times.

And so perhaps such a debate should be called: "How do I get from Spain?".

Dr Hywel Francis is the author of Miners against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War (2012). He was until 2015 Labour MP for Aberavon.

- Published13 July 2016

- Published28 June 2011