M4 motorway: Wales' 'economic lifeblood' and commuting Achilles heel

- Published

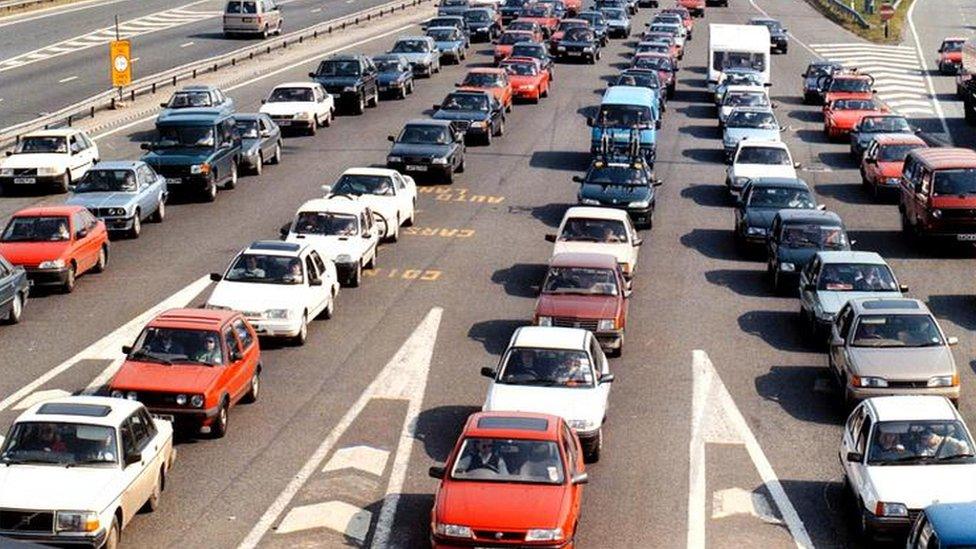

The new M4 prepares to open around Newport

Some say it is one of the most important creations in Welsh history. For most, it is just 78 (125km) miles of tarmac.

But whether it is your yellow brick road to new horizons or highway from commuting hell, the M4 motorway is culturally and socially ingrained on the lives of the 2.2m people who call south Wales home.

While Wales has less than 5% of the 2,000 miles (3,219km) of motorway constructed in 20th Century Britain, the London to south Wales highway is the economic artery of a nation still recovering from the loss of its heavy industry.

"The building of the M4 was the number one construction project in Wales in the 20th Century," said Wales' former First Minister Rhodri Morgan.

The M4 through Port Talbot

"It was and still is the lifeblood to industry in south Wales. We take it for granted now but life without the M4 in Wales is unimaginable, not just for business but socially and culturally."

The 2014 Nato Summit in Newport, golf's 2010 Ryder Cup, external at Celtic Manor and football's 2017 Champions League final at Cardiff's Millennium Stadium are world famous events that Wales may not have been awarded without a suitable road infrastructure.

The phrase 'ideally situated, convenient to the M4' is a staple for Wales' economic development team but the Welsh Government, which is proposing a relief road around Newport, know if the M4 sneezes, south Wales catches a cold.

"As Wales diversified from its traditional coal and steelmaking industries, the M4 was absolutely integral to attracting new businesses to an area of the country that was previously pretty remote," said Mr Morgan.

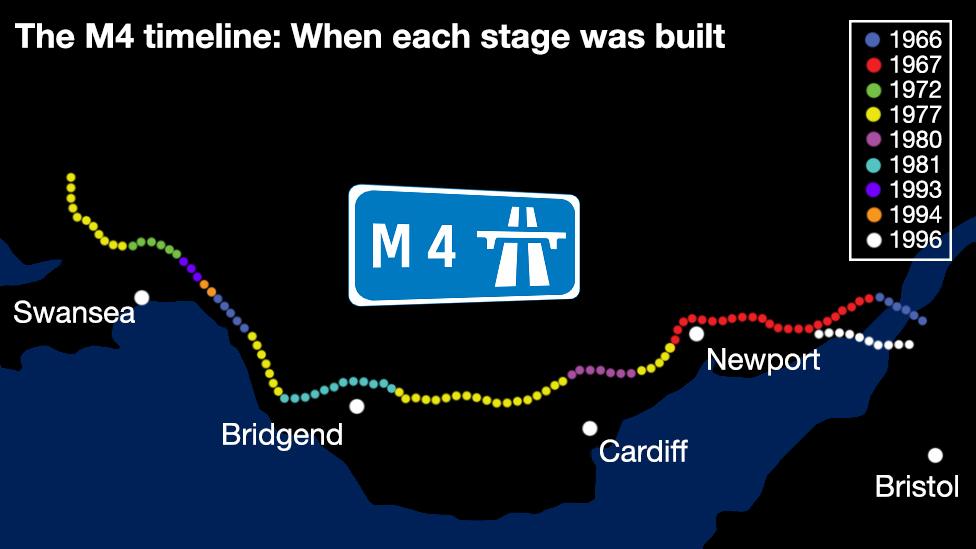

Now as the Severn Bridge turns 50 on Thursday, it is also half a century since Wales had what was to become its first stretches of motorway.

Start of the journey

Relieving Port Talbot of congestion and bridging the formidable Severn Estuary was a new dawn for modern day Wales in 1966 - as road started to replace rail, mainly due to the infamous Dr Beeching cuts, external to the railway network in the 1960s.

While the Brynglas Tunnels in Newport and Port Talbot's flyover are more notorious for being traffic congestion hotspots, they are also working British motorway history which have raised south Wales' transportation expectations.

The Welsh demand for a highway and bridge across the River Severn dates back to the years following the World War One but was delayed due to the Great Depression, World War Two, post-war recession and financial priority of establishing the National Health Service.

"And during the 1950s, the Conservatives decided to build the Forth Bridge first because its political needs in Scotland were greater, whereas most of south Wales was regarded as immovably Labour," remembered Dr Martin Johnes, a professor of history and culture at Swansea University,

And the Welsh Office's former head of roads and major projects, Brian Hawker added: "The M50 motorway from Ross was given strategic priority over the M4 as the government wanted to get steel quickly from Port Talbot to the demanding car making plants in the Midlands."

Route planner

As motorway demand boomed across Britain, Westminster needed convincing of the financial justification of a strategic highway route to the relatively small population area of south Wales.

The construction of the Brynglas Tunnels, the first tunnels on the motorway network, were an engineering challenge

The Welsh delegation persuaded Whitehall a motorway was necessary for a faster link to Ireland - via the ports of Swansea and west Wales - and today the M4 forms part of the 4,000-mile (6,437km) European highway E30 that links the Irish port of Cork to the Russian city of Omsk.

The M4 route - initially due to end at Tredegar Park in Newport, now junction 28 - was strategically located through the middle of Newport to generate traffic numbers to justify its existence to government.

Then, Newport was unique as, despite being a relatively small town, it had five motorway junctions to attract local traffic to use the M4 as a bypass and not a long-haul route, the intention of a motorway. A subsequent study has shown 75% of traffic in the tunnels - and 81,000 vehicles used the tunnels daily in 2015 - are local.

But the tunnels problem could have been averted as Mr Hawker explains: "The reason the tunnel is at Brynglas is because there was a railway line across the side of Brynglas Hill. Otherwise we would have cut through the hill, leaving room for possible motorway widening.

"The shame is Dr Beeching's cuts closed that line half way through construction. With a little planning, some of the subsequent traffic problems could have been averted as we would have built the cut through the hill.

The Severn Bridge was the first toll bridge on the British motorway network

"Other routes around Newport were considered but the northern section was chosen, not just to serve Newport but towns up the valleys like Pontypool, Risca, Newbridge, Caerphilly and the new town at Cwmbran."

The 'Newport bypass' opened in 1967 - the year after the Severn Bridge - but the Welsh Office immediately demanded an M4 extension following its formation in 1965.

"There was a growing urgency to the need to act, arising from the election of Plaid Cymru's first MP in 1966," added Dr Johnes.

"This was a political development of near epic proportions; suddenly the frustrations over how Welsh economic and cultural needs seemed to be marginalised by the status quo had translated into nationalist votes."

Cardiff council's favoured route for the M4 through the capital was along the current A48 (M) or Eastern Avenue, past the University of Wales Hospital, through the Gabalfa interchange before turning right through the heart of historic Llandaff and joining the current M4 line just east of what is now junction 33 and Cardiff West Services.

"Planners had the intelligence of the problems with congestion at Newport and new guidelines that motorways should be intercity routes with long sections between junctions so building to the north was the most sensible and sensitive option," added Dr Johnes.

But progress was slow.

"The slow release of funds, arguments over routes and subsequent public inquiries hampered progress," recalled Dr Johnes.

"By 1974, as the incoming secretary of state for Wales would later note, the motorway's expansion had 'crunched to a halt'. A year later, a newspaper was claiming the road between Cardiff and Swansea was still one of the worst linking two major towns anywhere in Europe."

The 'Cardiff bypass' was completed in 1980 north of the city - as plans to build a new town at Llantrisant were shelved - and with the M4 'Bridgend bypass' to follow in 1981, the car journey time from Swansea to London was cut to just over three hours (on a good day) within the space of eight years.

Game changer

While the narrow Brynglas Tunnels highlighted the importance of forward-planning should demand outdo capacity, the imposing Port Talbot flyover played a part in changing legislation.

"The bypass at Port Talbot is very intrusive on residents - so much so locals often hang their washing out under the flyover," said Mr Hawkins.

"That situation and the building of Westway flyover in east London played a part in the government's 1973 White Paper Putting People First where it made it illegal to build motorways so close to built-up areas."

Lessons were learned in the early days of motorway building but as Dr Johnes concludes: "The simple existence of the road changed people's mental geographies of distances, even contributing to a sense that Wales itself was not so remote.

"Simply getting from one place to another is now quicker, smoother and less frustrating that ever before. And for that reason alone the M4 is one of the most important places in the history of Wales."

- Published8 September 2016