Ford Bridgend loses out in global race

- Published

The decline that is on the horizon for the Bridgend engine plant is the latest phase of a shift in gear that has been going on since the early 1990s.

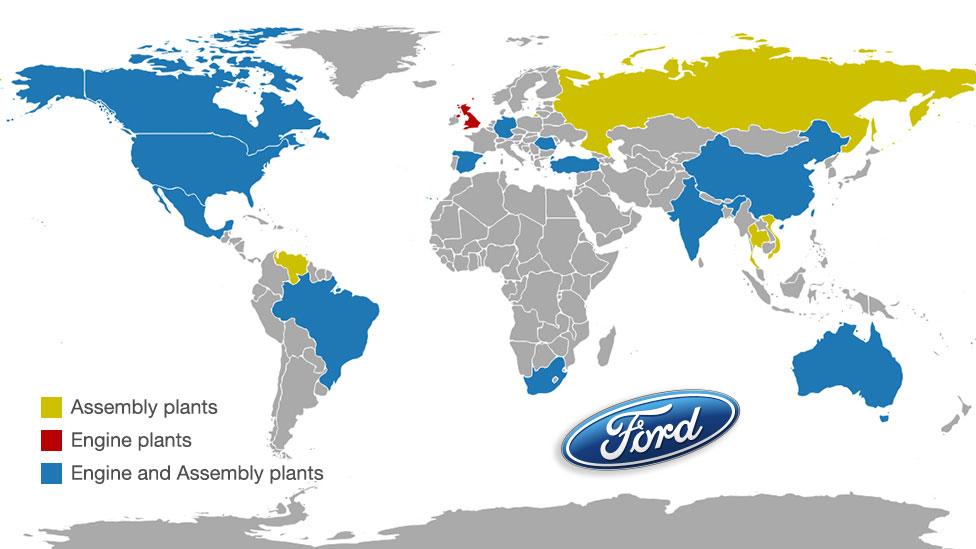

The change in emphasis goes back to 2008 and the "one Ford Plan" - the decision at Ford HQ in Dearborn in the States to "go global."

This meant operating as a global company and no longer having Ford UK and Ford Europe making different designs of cars compared with the USA and rest of the world.

Stand-alone engine plants are a rarity in Ford's global operations

In contrast it would become a more centralised global operation with the same models selling across the world and investment going to the plants that can prove they are the most efficient.

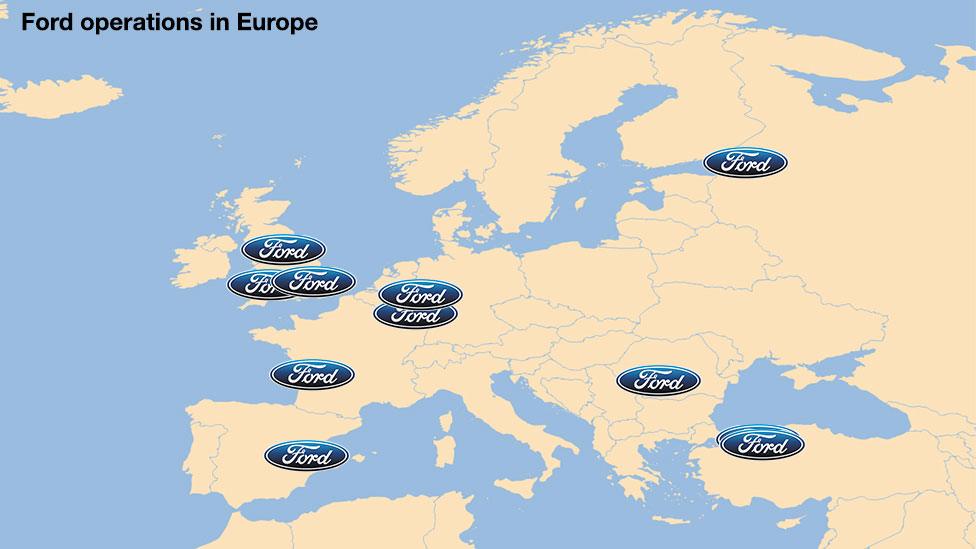

For Wales, and the Bridgend engine plant, that meant it would not just have to compete to be more efficient than Ford's engine plants in Valencia and Cologne - which it had done successfully for decades - it would in future have to compete globally.

Bridgend is one of a number of plants in Ford's European operations

When Ford decided to cease car assembly in the UK, that made the landscape more challenging for Bridgend.

The Halewood plant in Liverpool, external stopped assembling cars for Ford in 1997 and concentrated on Jaguar and later vehicles for Jaguar Land Rover. Ford also stopped assembling cars at its Dagenham plant in Essex in 2002, external, concentrating on engines instead.

In 2013, the Transit van factory in Southampton closed, marking the end of Ford making vehicles in the UK.

Now engines made in Bridgend are shipped all over the world to be put into cars before being sent back to showrooms in the UK . You may well be driving around Wales in a Ford car with a Welsh engine but the car will probably have been built in Germany.

With Ford's European car assembly also based in Romania, Russia and Turkey, it is now a long and less efficient way of supplying engines to production lines.

With Brexit now on the agenda and the possibility of trade barriers, duties - taxes in effect being put on UK products entering the EU and also goods flowing from the EU to the UK - factories making engines here will have to be even more efficient to be kept open by Ford.

For the Bridgend engine plant all these factors coming together is increasing the pressure.

If an engine entering Valencia had a tariff added to its cost only to be then shipped back to the UK with another tariff put on it then it is easy to see why Ford might consider in the future using engines made in Valencia in cars assembled in the same plant.

The story behind how the Ford engine plant in Bridgend was built between 1977 and 1980.

HOW FORD CAME TO BRIDGEND

Ford chose Bridgend for its new engine plant in the summer of 1977 after competition from elsewhere in Europe, chiefly from Ireland.

The company had gone back to the Welsh Development Agency, which it impressed despite rejecting deals for two smaller projects. It needed an engine for its new model - code-named Erika - which was designed to rescue the company from the doldrums, especially in Europe and America.

The car became the next generation Ford Escort, and would be built at Halewood on Merseyside and at Saarlouis in Germany from 1980.

The Ford factory being built in the late 1970s

The mark III Ford Escort - which was nearly called the Ford Erika after its development name

The American company looked at sites in Briton Ferry, Shotton and was close to choosing Llantrisant before opting for development land in Bridgend.

The deal was finalised after the then Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan - also a Cardiff MP - entertained the Ford Europe chairman at Chequers and then also invited Henry Ford - the grandson of the company's founder - to lunch at No 10.

The firm had concerns about strikes and Britain's industrial relations record.

But the deal was worth £36m in government money out of the £180m total cost - although there was also investment at other plants in the UK tied in. The grants for buildings and equipment also included £1m towards a new rail link to the plant.

By the mid 1970s and the fuel crisis, Ford was adapting its cars to be economical and for the family

The promise was 2,500 jobs but by the time it opened in May 1980, Ford had decided to take on only 1,400 workers.

Some of the work had already been switched to Valencia. The new Escort would have three different sized engines, not all made at Bridgend. Some would also go into the smaller Ford Fiesta. Executives had also been to Japan to see production techniques and the same number of engines could be produced there by just 800 workers.

But with industries like steel and mining in difficulty, there was still a big response in south Wales - 22,000 people applied for the new jobs and it would become one of the most important employers along the "M4 corridor".

The "Erika" and her successor would by the end of the 1980s be arguably the UK's most popular car with more than 1.6m models on the roads.

When Ford announced in 2015 that Bridgend has secured investment for the next petrol engine project called Dragon it said 250,000 engines would be made a year.

The plant has a capacity for three times that and at the time there were those who were concerned that this signalled the start of a run down of the plant.

The news in September that the proposed engine production was to be reduced to 125,000 was even more concerning, and has built up in recent months to unions looking for clarity from Ford about its intentions.

At the moment 1,850 people work at Ford Bridgend making the Sigma engine and also engines for Jaguar. It has planned to cease making engines for Jaguar in 2019 - the same year as production of the Sigma engine for Ford is due to end.

It is hard to see how Ford can retain anywhere near the existing level of workers when it is no longer making engines for Jaguar and with a relatively small turnover of new Dragon engines.

But it is not just the size of the workforce that could become unsustainable; the site is massive and it would become increasingly hard for local managers to argue the case that the plant makes economic sense to global Ford.

- Published1 March 2017

- Published7 February 2017

- Published15 September 2016

- Published9 September 2016

- Published6 September 2016

- Published25 March 2015