Ched Evans: Will footballer's rape case change anything?

- Published

After five years, Ched Evans has been cleared of rape. But what wider repercussions could his case have?

Could it lead to changes in the moral code of footballers off the pitch and has it highlighted the pitfalls of Twitter?

Ched Evans has been cleared of rape after a five-year campaign in which he always insisted he was innocent.

The Chesterfield striker was originally found guilty in 2012 of the rape of a 19-year-old woman who was two-and-a-half times over the drink-drive limit and deemed unable to give consent by the jury.

After a private investigation by his supporters, Mr Evans' conviction was quashed on appeal due to new evidence.

The not guilty verdict is the latest, and likely to be last, twist in the tale which started on 30 May 2011 at the Premier Inn in Rhuddlan, Denbighshire.

Over the past five years there have been two criminal court cases, two appeal court hearings, a contempt of court investigation and nine convictions due to Twitter trolling over the allegations.

Also, the case has been widely discussed and disagreed over.

While Mr Evans spent two-and-a-half years in jail, his accuser has been through two court cases and reportedly been hounded out of her home five times.

But what wider repercussions could the case have on football and society as a whole?

A timeline of events leading to Ched Evans clearing his name

This is not the first time a footballer has found himself under the spotlight for their activities off the pitch.

Earlier this year, ex-Sunderland player Adam Johnson was jailed for six years for grooming and sexual activity with a girl aged 15.

Mr Evans freely admitted in court having taken part in a threesome and cheating on girlfriends previously.

After his arrest, he told police he "could have had any girl" out in Rhyl that night.

"Footballers are rich, they have got money and that's what girls like," he said - remarks he later admitted he found "cringeworthy".

He said professional players were not entitled to anything.

Criminologist Dr Adam Lynes, from Birmingham City University said: "There is a sense that power, status and wealth gives you a moral monopoly on behaviour and forcing those on other people, it gives some footballers the sense they can do that.

"It is easy to access and impress young women who look up to you, and take advantage of that wealth and status."

Mr Evans returned to football after being signed by Chesterfield in June

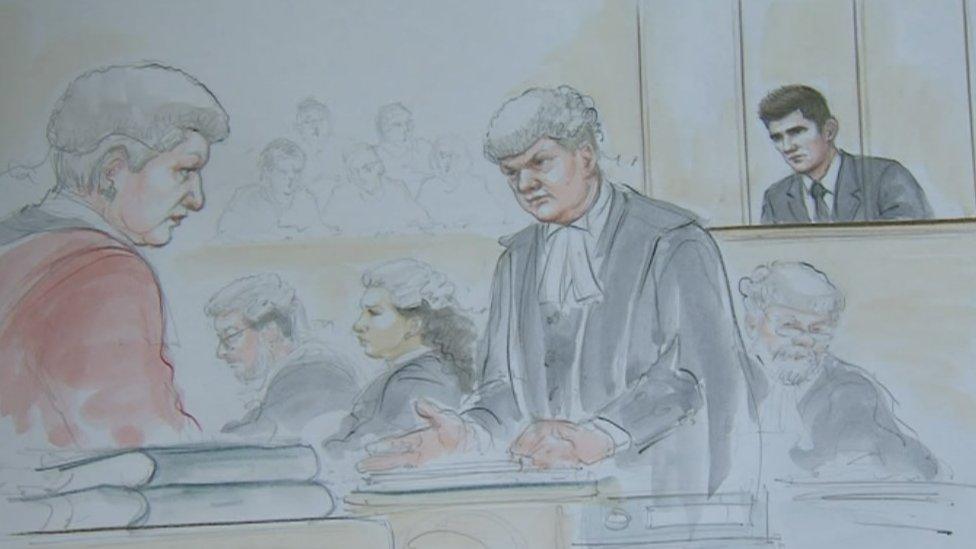

Mr Evans gave evidence at Cardiff Crown Court in the new trial

Ched Evans was playing for Sheffield United at the time of the incident

After Mr Evans was released from jail in 2014, then FA Chairman Greg Dyke said on Radio 5: "The whole story was pretty sordid in the first place, whether or not it was a rape it was still pretty sordid even if it hadn't been a rape."

He later released a statement which said the case could influence changes to the FA code of conduct to "recognise the unique privileges and responsibilities that come with being a participating member of the national game".

When Mr Evans sought to return to football on his release he struggled to find a football club that would take him on, with some having to pull out due to sponsorship and high-profile complaints.

Eventually he signed for League One Chesterfield in June on a one-year contract.

Richard Garside, director of the centre for crime and justice studies said: "Clearly there is some kind of notion that footballers are role models and there is some kind of notion that individuals should not continue to have a public role if they have been convicted of an offence.

"My concern is that those people who feel strongly that he should not be a footballer are confusing the question of practice with the appropriate provisions of a criminal sanction. The court does not impose unemployment as a punishment.

"My view on life after the crime remains the same regardless of whether the original verdict is held or he is acquitted. His return to work should be on the basis of footballing judgement.

"Part of a law-based society is that you respect the decision of the law rather than fall back on informal justice imposed and handed out by members of the community who feel strongly about certain matters."

Ched Evans was given a five year jail sentence in April 2012

Who is Ched Evans?

Born Chedwyn Michael Evans in St Asaph, Denbighshire, on 28 December 1988

Started playing football aged eight, signed by Chester City aged 12, before moving to Manchester City two years later

Before his 2012 conviction, he was a promising young striker who had played for Wales 13 times

Also played for Norwich and was with Sheffield United, who bought him for £3m, when he was convicted

His fiancée Natasha Massey has stood by him since he was arrested - her father Karl Massey reportedly helped bankroll the footballer's appeal

The couple have a son who was born in January.

Whether the not guilty verdict will further back those who called for Mr Evans to be allowed to return to professional football is yet to be seen.

But the repercussions of this case, and others like it, are already clear in steps being taken by clubs.

Sex education classes for footballers have been run for young players at Brighton and Hove Albion and Reading to explain when, in law, consent can be said to have been given.

It was this specific question of consent that Mr Evans' trial was centred around.

He insisted the woman had been in a state to consent. She said she could not even remember meeting him that night. It was this point on which the trial hinged.

Mr Evans was accompanied to court by his fiancée Natasha Massey

The woman at the centre of the case against Mr Evans was vilified on social media after the initial trial.

She was named on Twitter by some of Mr Evans' supporters - a criminal offence as the law gives victims and alleged victims of sexual offences lifelong anonymity.

In one of the first cases of its kind, nine people were fined £614 for naming the woman, under the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992.

The case has been held up as an example that posts on Twitter are not exempt from the law.

Mr Evans had not played professional football since 2012 until he was signed in June

Media lawyer Christopher Hutchings said: "This was one of the first cases of this kind and it is extremely rare that this situation has arisen so far.

"The hope is that these cases are used to draw people's attention to show the public that they must be careful retweeting things and discussing them on social media.

"Otherwise they could face civil action for defamation, sanctions from the social networking sites involved, as well as criminal prosecution."

But campaigners are concerned complainants in high-profile cases could be deterred from coming forward if they fear abuse or exposure on social media.

Jill Saward, who was raped in 1986 when a gang broke into her home, said: "It could totally put other people off reporting rape or sexual offences.

"You will find people won't come forward because it is only going to get worse for them if they do. But I would encourage people to come forward and get help, even if they feel that it is going to be difficult.

"There is a lot of help out there."

- Published11 October 2016

- Published10 October 2016