Derek Brockway meets Cardiff scientists fighting sepsis

- Published

'We see the severe side when infection turns to sepsis'

From the moment a patient comes through the door of an A&E department with signs of sepsis, time is already rapidly running out to save their lives.

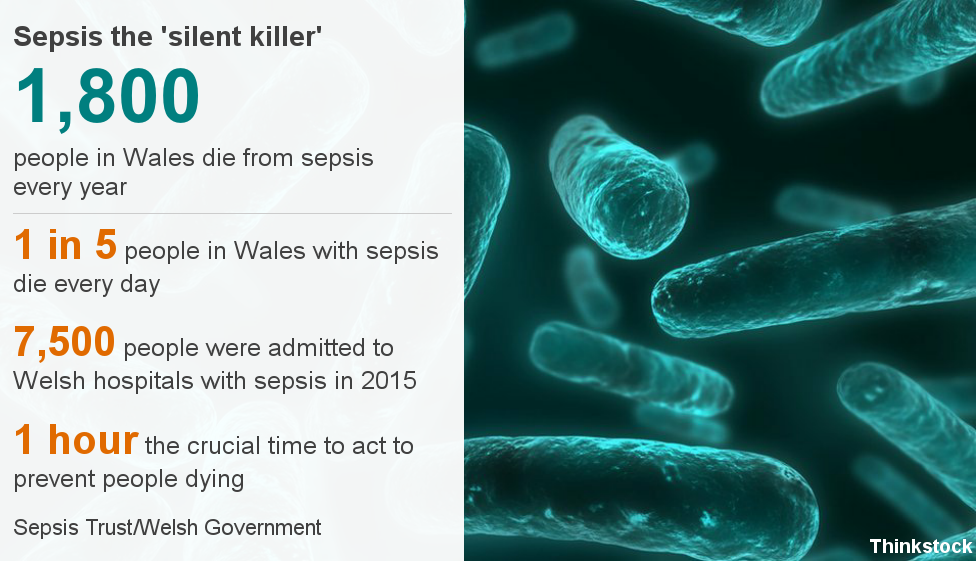

About 1,800 people in Wales die every year from sepsis which can start from something as mundane and ordinary as a simple cut on a finger, a cough or even a urinary tract infection.

BBC Wales forecaster Derek Brockway's life was turned upside down when his dad Cliff died from sepsis in February 2015.

After making a programme called Understanding Why My Dad Died, he was invited to the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff to meet a team of scientists trying to stop the condition in its tracks.

Derek's parents Cliff and Joan Brockway fell in love as teenagers and married in 1954. His dad died in February aged 82

In the laboratories not far from the wards, a team of almost 200 scientists are working on finding ways of preventing, fighting and treating inflammation and infection - so patients like Derek's dad have a chance to survive.

The team at Cardiff University's Systems Immunity Research Institute (SIRU), headed by Prof Valerie O'Donnell and Paul Morgan, is undertaking research to understand the causes of inflammatory diseases like sepsis, and why some people can die while others are fine.

The scientists are looking at everything from preventing infection to the global problem of antibiotic resistance and how to stop inflammation taking hold in the first place.

Prof O'Donnell, who co-directs the initiative funded by about £90m of grants, said she hoped the research they were doing would lead to fewer people getting serious infections like sepsis in the first place.

"We live with millions of bugs in our bodies all the time, when they get into the blood stream they are not meant to be there, and you get this massive inflammation that causes all the organ damage," she said.

"If we can understand better how infection and all the underlying process of inflammation interact in the early stages, we can design better ways to prevent it becoming sepsis.

"Once it gets that far, it's very difficult to stop."

ICU consultant Dr Matt Morgan joined the research team 10 years ago after he faced parents whose son had just died from pneumonia which turned to sepsis.

He wanted to learn more about the condition and now feels he could have told those grieving parents more about why their son died.

"He was fit and well, in his mid-20s, I was in the room when his parents were being told. Being a new parent at the time, it affected me," he said.

"Even with the best treatment, given antibiotics within an hour, one in five people will die - that's not good enough."

Sepsis is a condition which affects about 7,100 people in Wales every year

Derek Brockway on understanding sepsis:

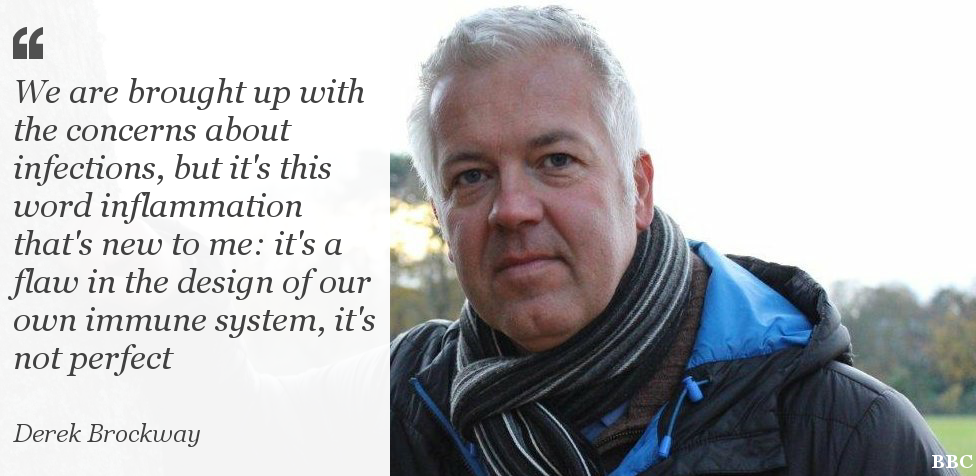

"It was interesting to see the work going on behind the scenes that you are not really aware of.

"I had heard of inflammation but not in that context. It's an eye opener, the fact our bodies can't deal with these infections and they go into shut down. Our immune system can't seem to handle it, it's a flaw in our design.

"It was really good for me to meet these doctors and scientists, to find out more about the important research they are doing which will try and help to save more lives."

Dr Morgan said that while sepsis claims more lives than cancer in the UK every year, the advances in treatment are a long way behind.

"If you walk into intensive care here today and you are critically ill, the test we will do is very similar to what was done at the dawn of the germ theory in the 1880s.

"We will take some blood, we will put it into a bottle of broth, wait a few days, look down a microscope.

"It's amazing the advances that have been made in cancer treatment, where it can be tailored to individuals, but similar advances in diagnosing and treating infection are only now emerging."

According to figures from the Sepsis Trust, for every hour someone does not get the right treatment their chance of survival reduces by 5-10%.

But current blood tests to find out if someone has an infection, when they get to hospital, can take up to three days as the bacteria needs to be grown in a lab.

"Even when they do come back, the tests are not always conclusive and as every patient is unique there is no guarantee they will react to the treatment in the right way," head of infection, Dr Ian Humphreys, explained.

"With some bacteria, around 70%, it is not possible to grow them in a lab, meaning there is a lot of guess work involved which leads to an over prescription of antibiotics - sometimes when they aren't even needed."

Dr Matthias Eberl heads a team which is working on ways to speed up this process, by understanding the body's own immune system to create personalised responses.

This includes developing a strip test - similar to a pregnancy test - to check urine. It could tell them whether someone has an infection or not, within five or 10 minutes.

"We talk about infections all the time in terms of bugs but it is extremely difficult to pin down whether the patient in front of you actually has an infection or which kind," he said.

"As a way to pinpoint the bug, we try to understand the inflammatory response and develop biomarkers - every type of bug is different and they interact separately with our immune system activating distinct components.

"If we better understand how the immune system responds [to inflammation] we can develop ways to harness its good effects while trying to prevent it attacking our bodies and causing harm."

While the research being done in the Cardiff laboratories is pioneering and paving the way for better treatment, it is still a long way away from being used on the hospital ward and even further from a cure.

Prof O'Donnell said: "It's still many years before a patient will be able to come in and within a couple of hours we will be able to say not only that it's a particular bug, sensitive to a specific antibiotic, but importantly it's activating certain arms of inflammation that we can then dampen down to stop the organ damage.

"If you die of cardio vascular disease, diabetes, maybe even of dementia, it's inflammation that's killing you - so nearly everyone is dying of inflammation, including sepsis, which is a sobering thought."

Derek Brockway: Understanding Why My Dad Died is available on BBC iPlayer

- Published17 January 2017

- Published28 November 2016

- Published28 November 2016

- Published26 January 2016

- Published13 July 2016

- Published29 November 2016