Could Portugal's radical drug approach work in Wales?

- Published

The first thing a Portuguese police officer will tell you about drugs is that they are still illegal.

We gathered that as we sped our way through Lisbon in a convoy of vans, escorted by heavily-armed narcotics police.

"It's been a while since I've gone through red lights with sirens and blue lights," chuckled Arfon Jones, a former officer himself.

BBC Wales' Week in Week Out programme brought the North Wales Police and Crime Commissioner to Portugal to see how a radical new approach to drugs was working out.

Plaid Cymru's Mr Jones has led calls for cannabis to be legalised for medicinal purposes and ultimately wants the legalisation of all drugs to be considered.

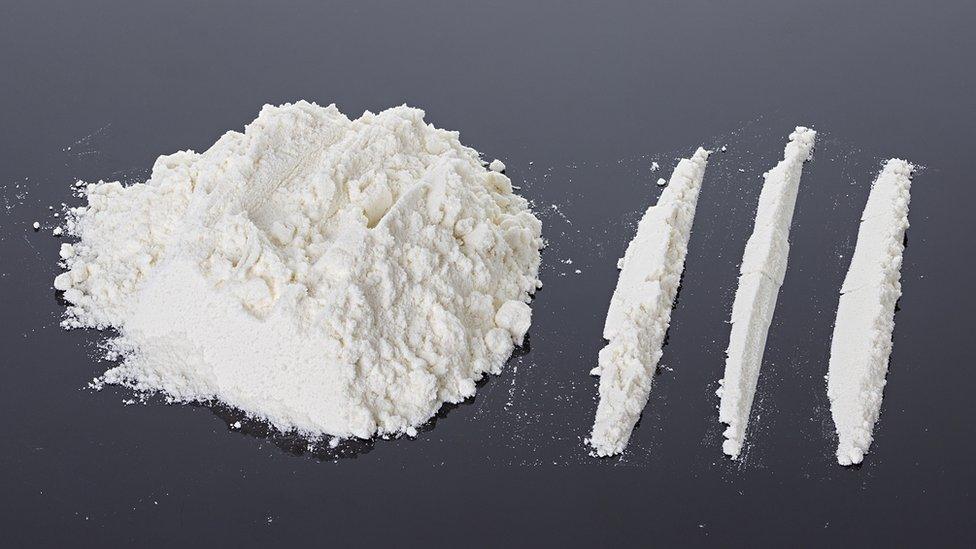

We spent three days filming with him in the Portuguese capital and watched as, under armed guard, vans were emptied of three tonnes of heroin, cocaine and cannabis, all seized from drugs gangs, and burnt in an incinerator.

Portugal lowered the penalties for drugs possession 15 years ago, but traffickers and dealers still face jail.

Police, privately sceptical at first, say the change has worked for them.

"It frees up our time so we can go after the serious and organised crime," Artur Vaz, the narcotics police chief told us.

It is the other end of the scale - with the drug users - where you see something really new.

Arfon Jones with Dr Joao Goulao, Portugal's national drug co-ordinator

I filmed Pedro, in his early 20s, being dealt with by a body unique to Portugal called the Dissuasion Commission.

Two casually-dressed commissioners questioned him about his private life.

He had been referred here because police found him with slightly more than the 10 days' worth of drugs people are allowed.

A criminal court found he was not dealing drugs, so now the Dissuasion Commissioners were working with him.

This was quite unlike anything I had seen before and different from so-called drugs courts.

"If a user needs help, I am in a much better position than a judge," commissioner Nuno Capaz, told Mr Jones.

"He hands out a sentence. That might work if someone robbed a bank, but not if you are a drug-user."

And because the commissions are run by the health department, he says he has a direct line to treatment services, speeding up referrals.

"In Portugal decriminalisation isn't the big thing," said Brendan Hughes, of the European Drugs Monitoring Agency, also based in Lisbon.

"They designed a whole package."

I took Mr Jones to this EU agency because it is an independent evaluator of international evidence.

Mr Hughes told us it was the move from criminal justice to the health department that was making the difference.

"The Portuguese change is coherent and consistent," he added.

And just as important, say supporters, is the boost given to health practitioners.

Psychiatrist Miquel Vasconcelos showed us around the Taipas Centre, where we watched three recovering addicts receive one-to-one physiotherapy.

What were the benefits of decriminalisation? we asked.

"We have had more resources. More social awareness that this is a disease not a deviant behaviour, and the people affected by it are more tolerated. And we have felt we have had more acceptance as professionals," he said.

We were told they got the waiting time for treatment following referral down to one week.

It has since risen to four weeks following Portuguese austerity cuts, but that is still quicker than in Wales.

We were coming to the end of our visit, but I still had questions. International comparisons are difficult and campaigners on all sides can be selective with statistics.

And just because one policy lever is pulled and something follows, like a rise or fall in heroin users, that does not mean the policy caused it.

So I took Mr Jones to meet the architect of Portugal's drug policy, Dr Joao Goulao, and asked him if it could work in Wales.

"Our drug problems were present across all social groups - this was a factor in favour of this law," he said.

"Probably in your country it's much more confined to marginalised people and that makes it more difficult [for] the acceptance of the rest of society."

In Wales, some oppose any policy that might be seen as going soft on drugs.

Rhondda Labour MP Chris Bryant said: "What I have seen is people's lives being dismantled by drugs… and I just don't want us as a country, as a parliament to say 'you know what, play with that, have a go, it doesn't matter', because it really does."

I pointed out that many reformers say they are not promoting drug use, only trying to help addicts.

"See, I don't believe that," he replied, "and the problem is… with so many drugs you cannot know what the reaction will be... the classic instance… is cannabis… there has been so little research into cannabis.

"So my anxiety is that you… could open that door but you simply don't know where it is leading to."

Back from Portugal, Mr Jones is still in favour of decriminalisation.

"I learned in Lisbon you have to do three things: decriminalise, move drug use away from criminal justice and into health and then boost spending," he said.

"Only then can [you] reduce harm to problem drug users and society."

Watch Week In Week Out's Cop-out on Drugs is on BBC One Wales at 22:40 GMT on Tuesday.

- Published7 March 2017

- Published6 March 2017

- Published6 October 2016

- Published24 October 2016