Hughesovka: The city founded by Welsh migrants

- Published

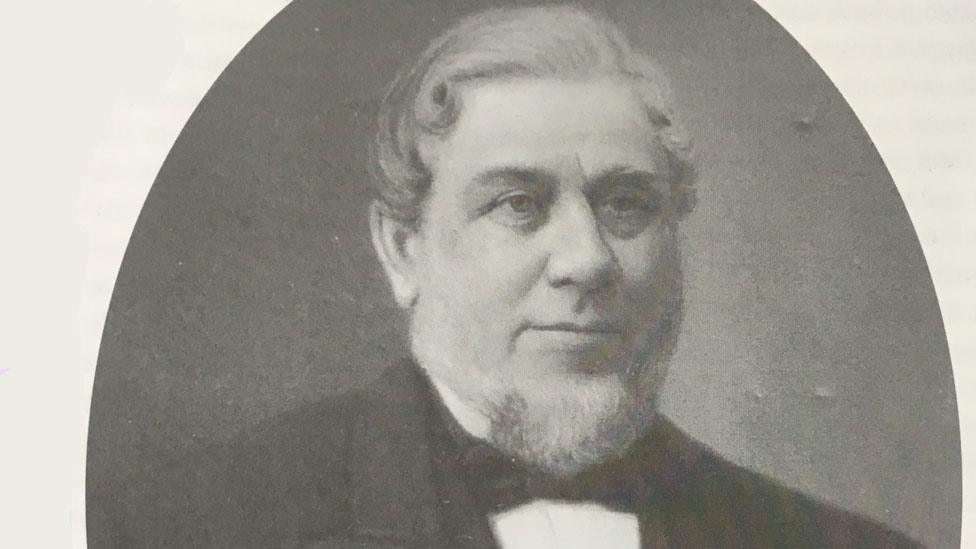

John Hughes was the son of a Merthyr iron engineer

The story of a Welsh ironmaster and migrant workers from south Wales who founded one of the Ukraine's largest cities is being told in Merthyr Tydfil this weekend.

The well-travelled Victorian migrant routes from Wales to America, Australia and New Zealand are better known.

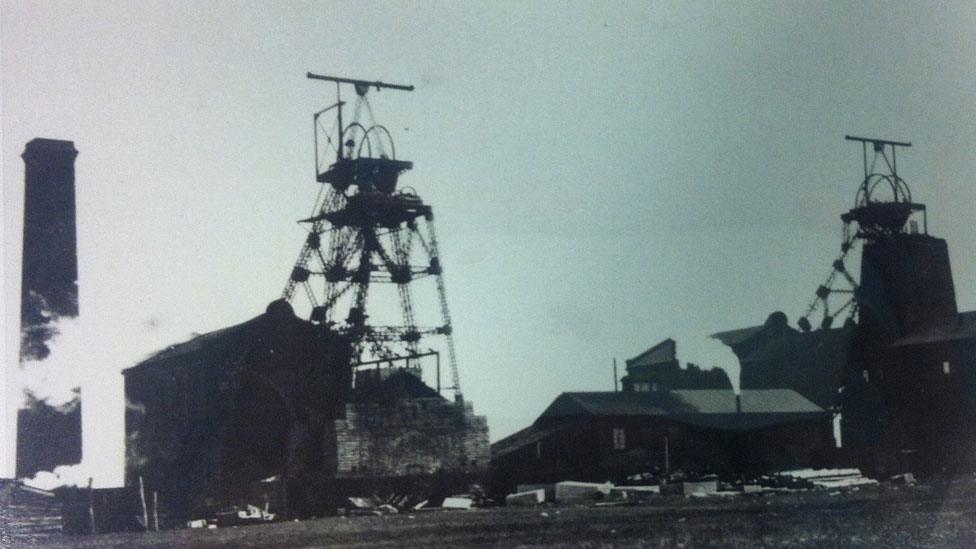

But in 1870, John Hughes and about 100 workers and their families sailed in eight ships to Russia. They built an iron works and collieries and over the next two decades established a new town - called Hughesovka.

It included a thriving ex-pat community, in what is now known as Donetsk, a city of one million people.

An all-day event at Merthyr's Old Town Hall will bring together archive and new photography, film and music to re-interpret the story of the Welsh pioneers.

Called Enthusiasm, it has been named after an early documentary film about the Ukranian mining communities which followed and has been set to new music by Welsh composer Simon Gore.

But who was John Hughes? The Cyfarthfa-born industrialist was in his mid 50s when he came to the notice of the Tsarist Russian government, under Emperor Alexander II. He had built his own foundry in Newport but made his name in developing armour plating for ships. The Tsar wanted his expertise for a naval fortress on the Baltic.

Hughesovka included collieries - with pitheads which would be familiar to migrants from south Wales

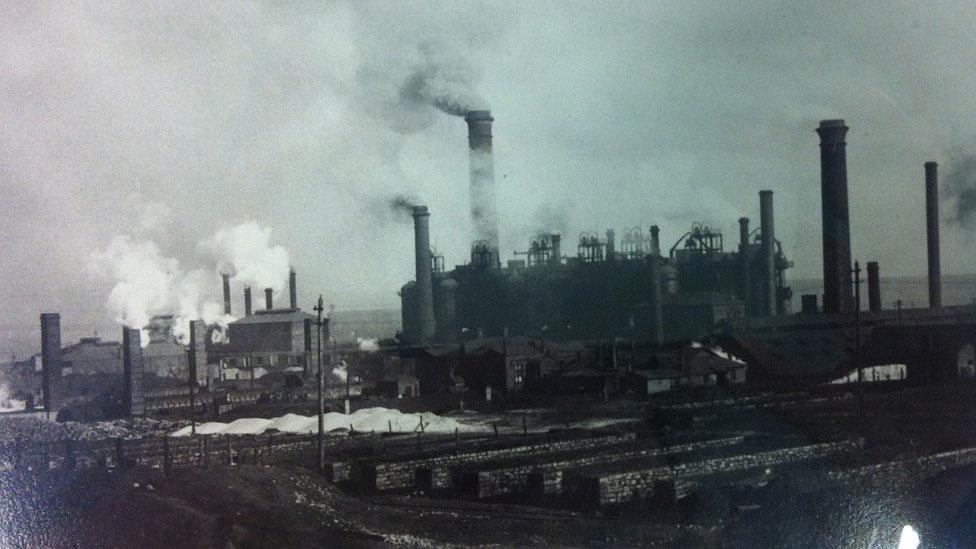

Hughesovka was established around metalworking - this is a photo from the 1890s

It led to an opportunity for Hughes to develop his own works in Russia, which would include a factory for forging railway lines.

Times were hard economically back in south Wales so this was a new opportunity for workers from south Wales and England. Some brought over their families. They were a mix of skilled workers, engineers and managers in Hughes's new company.

This migrant middle class was swelled by labourers who flocked from all over the Russian empire.

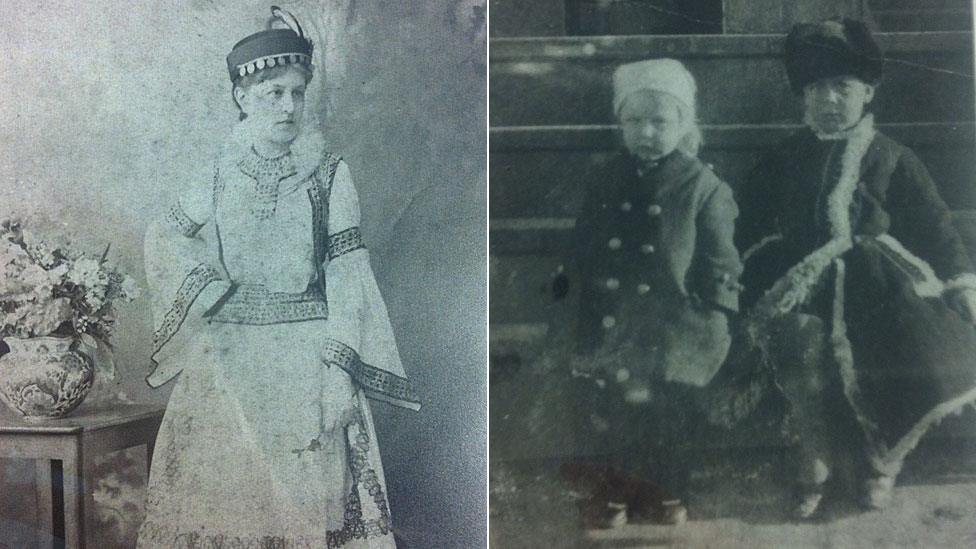

The Welsh and English migrants formed a very middle class community

The community had its own hospital, schools and Anglican church. They also enjoyed tennis, sailing, amateur dramatics and other pleasures which were part of respectable late Victorian and Edwardian society.

"There is a story of how one woman in 1906 wanted an authentic English tea party and was trying to get a proper teapot," said Dr Victoria Donovan a lecturer in Russian history at the University of St Andrews.

"She was trying to teach her Russian maid to make British tea properly but she kept getting it wrong."

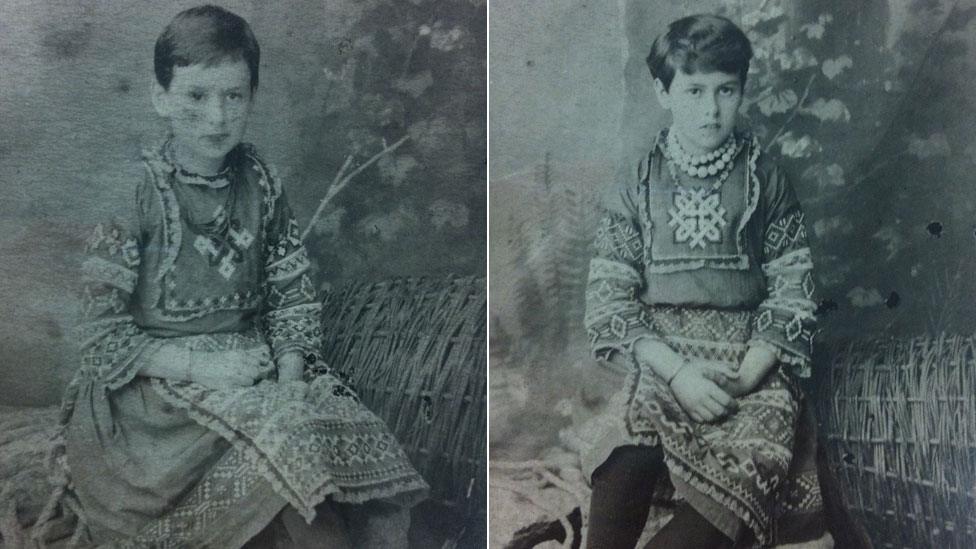

A Hughes family member (left) and children dressed in Russian winter wear

Members of the Hughes family adopting Russian peasant costume

Artist and curator Stefhan Caddick has worked with Glamorgan Archives, delving into its wealth of material, including letters, postcards and photos.

They include romanticised images of children from quite middle class backgrounds, dressed in Russian peasant costume.

Co-curator Dr Donovan added: "Over time there is evidence of greater integration and assimilation. Some were there for 30 years and acquired Russian language skills."

Hughes died in St Petersburg in 1889, still working at 74, although his four surviving sons continued running the works.

His town had grown to a population of 50,000 by the turn of the 20th Century. While Hughesovka was well established, Hughes's own personal story is still a little sketchy.

"You get a sense John Hughes was very paternalistic towards his British workers - he had semi-philanthropic ideas, in common with other entrepreneurs of the 19th Century," said Dr Donovan.

Two Russian labourers, of the many who flocked to the growing Hughesovka from across the empire, but life was harsher

The Welsh chapter in the Hughesovka story came to a dramatic end with the Russian revolution - a century ago. Hughes's descendants and British migrants were forced to return home, with anything they could carry.

"A lot knew what was coming and left of their own accord although there are stories of women sewing their jewellery into their dresses for safe keeping, " said Dr Donovan.

"There is one story of a man of the managerial class who had decided to stay and ride it out who was turfed out in a wheelbarrow by the Russian workers under him."

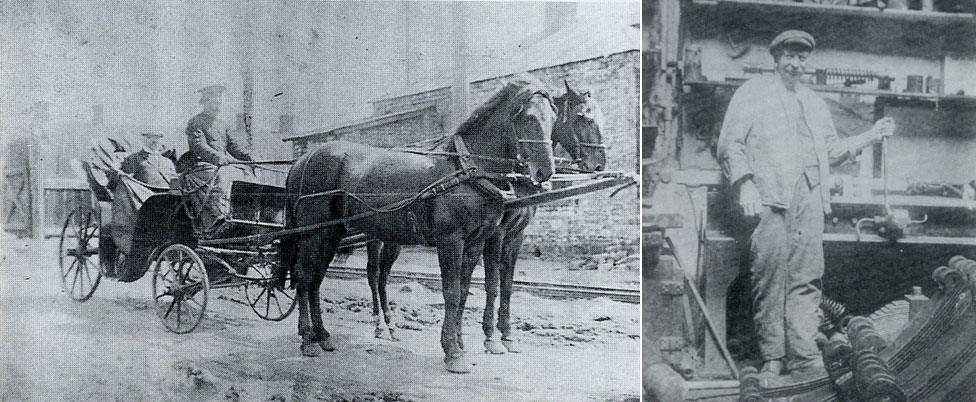

Thomas James arriving for work as a mine owner in Hughesovka - and working in Cardiff in a repair yard after the Russian revolution in 1917

This grainy photo shows Thomas James (right) as an elderly man living in Llantrisant, his cap a reminder of his time in Russia

Dr Donovan said workers dispersed to different parts of the globe, from Canada to the United States and back to Britain, some with nothing.

One of them was Thomas James. After the revolution, he ended up in Cardiff working as a labourer in a repair shop for the Taff Vale Railway "totally bankrupt, a rags to riches story, back to rags again."

James had owned a coal mine in Hughesovka, arriving for work in a carriage, and had won a medal from the Tsar for saving lives in a colliery disaster.

There is also an archive family picture of James as an elderly man in Llantrisant, in much reduced circumstances, but still wearing an eastern Asian style cap.

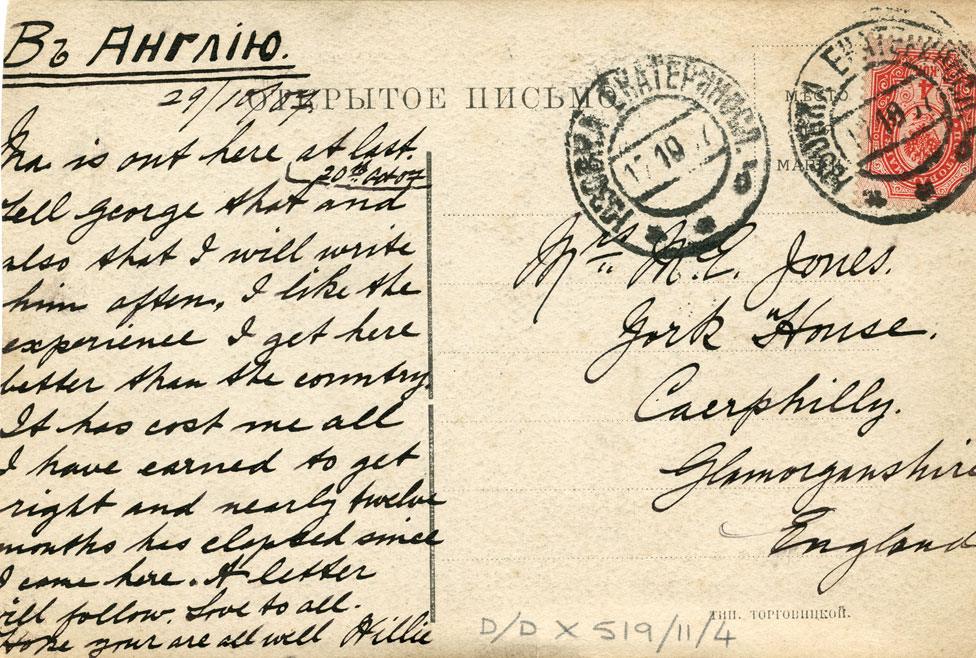

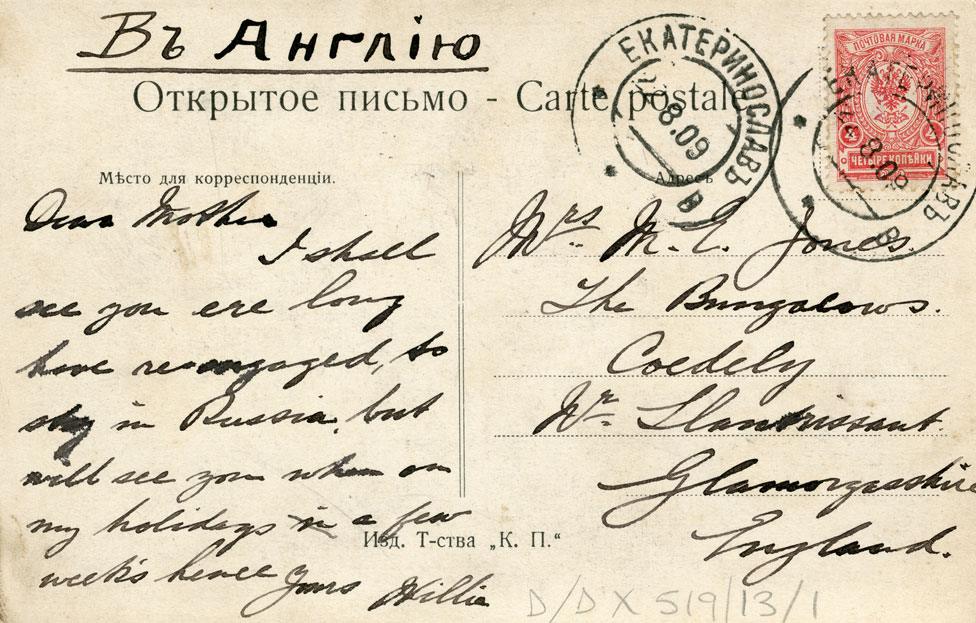

'I like the experience I get here better than the country'

This postcard written in 1909 from a worker to his mother back in Coed Ely near Llantrisant

Hughesovka became known as Stalino and eventually Donetsk, where mining and metalworking are still important industries today.

A statue to Hughes was erected in the city in recent years - and he is still of fascination locally.

Back in Wales, Hughesovka has been researched by Glamorgan Archives' head archivist Susan Edwards while a history was written a few years ago, external and Manic Street Preachers even recorded an instrumental Dreaming A City about it.

But Dr Donovan said it was a story that needed a wider audience as part of modern Welsh history.

"I'm from Cardiff and an historian of Russian history and was amazed to come across this - and then to find such a treasure trove in the archive. This is something which should be in our GCSE syllabus. Children learn about the Rebecca Riots but this a story that so few people know about."

"In Donetsk, they know more about John Hughes than in Merthyr Tydfil."

Contemporary photos from Alexander Chekmenev will also be on show of Ukrainian mining families still living in the war-torn Donbass region

Saturday's event will also draw on the theme of the migrant experience in and out of Wales, across the ages.

The words of Hughes's migrant workers will be read out by some of today's migrants living in Wales.

Mr Caddick said: "Putting together the exhibition, we've tried to do it in a quite a playful way - there are no vinyl boards that are holding static displays, we've left it quite porous.

"We've a big map which shows the journeys of John Hughes's workers - and what happened to them afterwards but people can plot their own journeys as well. It shows history as an ongoing process, not something that is set in stone."

Enthusiasm , externaltakes place on Saturday 1 July, 12:00-22:00 BST at the Redhouse, Old Town Hall, High Street, Merthyr and is free. Some elements of the exhibition will remain on show afterwards.

Donetsk today is Ukraine's fifth biggest city

- Published11 June 2012