Type 1 diabetes: 'A simple test could have saved my son'

- Published

Peter Baldwin was a popular boy who loved school

Peter Baldwin was 13 when he died.

He had become critically ill with undiagnosed type 1 diabetes and his body was shutting down.

Six days later he lost his fight.

His mother Beth believes four simple questions asked by GPs could help prevent similar deaths in future.

In her own words, Beth explains why she hopes Peter's story will lead to change.

"My life changed in a matter of days"

I'd been watching Peter in his hospital bed all night.

He was semi-awake - I was talking to him but he wasn't really responding. He kept trying to move the oxygen mask and he was just so tried.

About 6am one of the nurses walked past his room and she said to me "get your head down". I said "I'm ok" but she insisted: "He's ok, get your head down."

I was sat next to him and put my head down on a little pillow. I don't know what woke me up about 10 minutes later... I got a feeling.

The Baldwin family campaign for change in Peter's memory

I woke with a start, looked up and he didn't look right - he looked grey. I called the nurse and said "what's going on? This doesn't look right".

She came over, lifted his eyes... I don't know if she pushed the buzzer but within 30 seconds all hell broke loose.

Someone said "he's really not well, talk to him" and I just started screaming "come on Peter, I'm here, mummy's here".

Nurses came from everywhere, alarms were going off, doctors came in shouting for a crash team. One was doing chest compressions. They were trying to save him because he'd had a cardiac arrest.

I was shouting at him all the time to wake up and telling him "mummy is here".

A nurse said she would call my husband Stuart. He came as our house is only two minutes around the corner. We just watched in disbelief as a team of goodness knows how many doctors and nurses managed to restart his heart.

They took him to surgery, off to try to stabilise him. We went up to the surgical department, just waiting, waiting, waiting.

Just 24 hours earlier, on New Year's Day 2015, my son Peter - fun-loving, everyone's friend and so clever - had been at our home in Whitchurch, Cardiff.

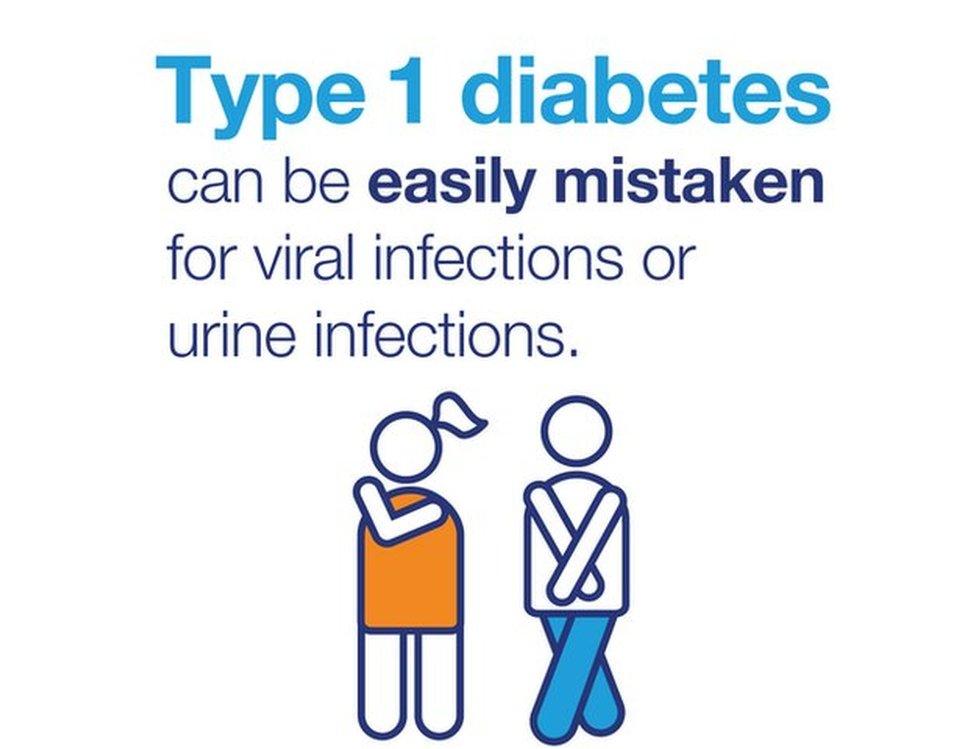

He had been ill with a chest infection. We'd been to see a GP and given antibiotics.

But I was so worried about how ill he was that I called my parents to come over - more for reassurance, I suppose. I wanted someone to say he was ok.

They took one look at him and said I should call an ambulance straight away. I started to panic. He was not breathing properly. I was very scared.

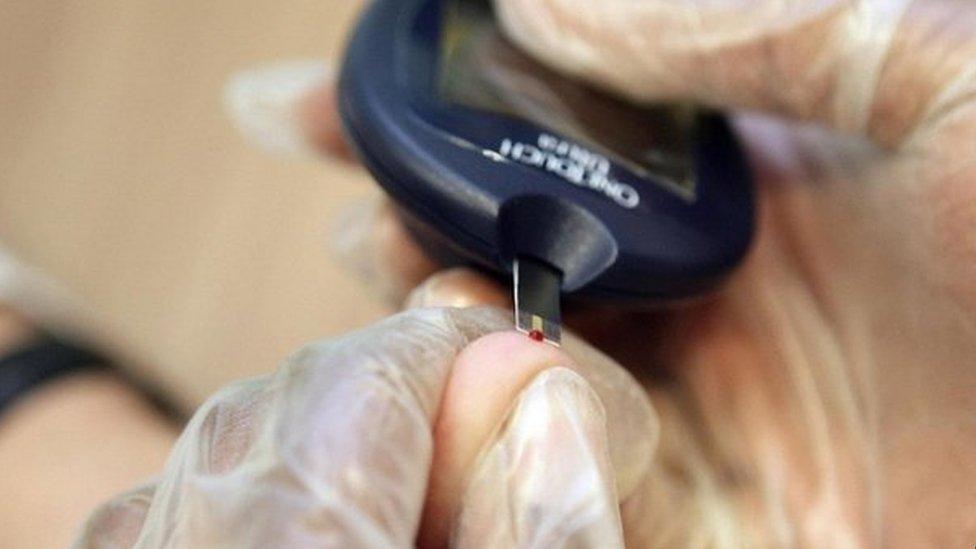

A first responder arrived at our house and one of the first things he did after giving Peter oxygen was prick Peter's finger for a blood test.

Within 30 seconds of coming he had diagnosed him as having type 1 diabetes - a condition where the body doesn't produce enough insulin.

I was told he was in a DKA - diabetic ketoacidosis - which is when your body starts to shut down if you haven't had insulin and it can lead to organ failure.

The ambulance journey to the University Hospital of Wales didn't take long from our house and soon Peter was in critical care in the high dependency unit, hooked up to a drip and oxygen.

Stuart went home at midnight to be with our eight-year-old daughter Lia. I remember saying: "Peter will be fine, come back in the morning."

I had no idea how bad he was.

After he had the cardiac arrest, the doctors and nurses saved him but when we were able to see him again we could tell his poor little body had been through the mill and back.

He was in the intensive care unit for four days. We sat by his side the whole time but he never really came back.

They said the DKA had gone too far and even though he'd been given medication, his body was already in shutdown mode and he couldn't fight it. That led to too much pressure on his organs.

They did all sorts of tests and he was put on dialysis. They came to us and said there were signs of damage to the brain and the outlook didn't look good.

On the day he died, it's all a bit of a blur... but they said he's not likely to make any recovery. The majority of the brain had been damaged and the machines were keeping him alive.

Hearing this broke us. We played music to him and read to him. We held his hands and rubbed his feet and kissed him a million times and told him how much we loved him and that everyone was praying for him.

Then at about lunchtime they said it's not really fair on him and we need to start making decisions.

I don't remember much about that day other than trying to process that my child was about to die. It's something you never ever consider and to this day I can't accept or comprehend.

Peter with his sister Lia

I have to be grateful we had six days to get our heads around it almost, even though we were hoping and praying for a miracle.

We had to switch the machines off and there was a last hope that he would start to breathe. But he didn't.

My daughter was eight at the time and she decided she didn't want to see him with all the tubes and machines.

Our family all came in - my parents, brother and sister - and said goodbye. Stuart's family all came down from Newcastle.

My mum was hysterical and I was trying to say to her "I tried". I felt like I failed him and there was nothing I could do - he'd gone.

My dad died when I was four and Peter was named after him.

I was praying to my dad "make sure Peter's ok. Save him". Now I know my dad's looking after him. I have to believe that. It's so hard.

We had to leave the hospital that night without him. My life turned completely upside down and I was heartbroken.

Beth with her son Peter

Within 24 hours my house was full of flowers. It's lovely for people to show their support but flowers will wilt and die - I thought the money should go to charity instead.

So we decided to raise money - the target was £500 and we reached that in an hour. It reached £10,000 in a week. It showed the impact Peter had had on people's lives.

Diabetes UK got in touch to thank us and offered to support us. We have been working with them ever since.

They have taken Peter into their hearts and shared his story as a way of helping raise awareness of the dangers of not diagnosing type 1 diabetes.

I'm immensely proud and heartbroken at the same time. This is Peter's legacy. I know he would have been a really good ambassador for type 1 diabetes. The fact he's not here means we have to continue in his spirit and on his behalf.

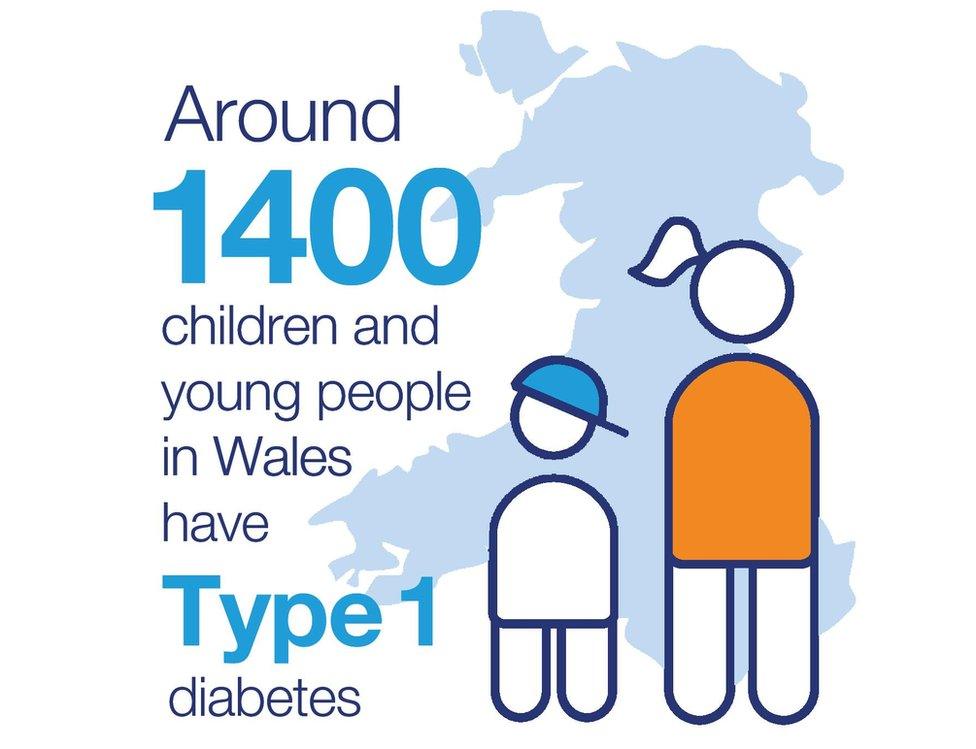

Since we started campaigning, many people and children have been in touch to say they were only diagnosed as type 1 diabetes as an emergency.

That should not be happening as four simple questions can raise the alarm for GPs examining a sick child. They call it the Four Ts test:

Toilet - going to the toilet a lot, bed wetting by a previously dry child or heavier nappies in babies

Thirsty - being really thirsty and not being able to quench the thirst

Tired - feeling more tired than usual

Thinner - losing weight

We want those questions to be mandatory for all GPs in Wales - they don't cost anything and take 30 seconds to ask.

If the answers are yes to these, there's a simple and accurate test available which GPs can carry out - a finger prick test, like you have if you go to give blood. It takes less than one minute and has instant results.

All GPs have finger prick monitors but not all have them on their desk. So we want working equipment they know how to use.

If Peter had had that test, we would have had a head start in helping him.

Peter wasn't a sickly child and the GP was correct to diagnose him as having a chest infection. But the examination stopped there without exploring if anything else was wrong, even though he was very ill.

That's why Stuart and I are leading Diabetes UK's national campaign called 'Know Type 1, external' to raise awareness of the symptoms.

We are also petitioning the Welsh assembly to ensure effective diagnosis and gave evidence to the petitions committee on Tuesday along with Diabetes UK Cymru.

Just a few weeks before he died, Peter had gone on a school trip to Germany to see the Christmas markets and he'd just started going into town with his friends - he was getting his first taste of independence.

He had an amazing group of friends and he used to play with them all the time, out on his bike and computer games.

When he moved to Whitchurch High School he was in the school council and he used to volunteer for stuff like the anti-bullying group. He did well at school and was active in all parts of school life and really took pride in what he did.

I'm angry, heartbroken, devastated and distraught that Peter's life could have been saved.

It's such a small test that is readily available. That's why it's so wrong. That's why we are determined changes must be made.

- Published13 June 2017

- Published2 May 2017

- Published31 May 2016