King Arthur: Welsh, English, Brythonic or made up?

- Published

Previous best guesses for the home of Camelot include Winchester, Monmouthshire, and Somerset

Who was King Arthur and how Welsh was he?

These are two of the questions up for debate at a new exhibition at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth.

From ancient Brythonic warlord to mythical chivalric king with a court anywhere from Wales to Glastonbury or as far north as Scotland - it is hard to separate myth, legend and fact.

According to curator Dr Maredudd ap Huw, these unknowns lie at the heart of King Arthur's enduring appeal.

"The beauty of Arthur is that he was - indeed, according to some 'is' - whoever you want him to be," said Dr ap Huw.

"There is some early evidence to suggest that there was an Arthur in the 4th or 5th Centuries.

"Though in all likelihood he was very far removed from the romantic depictions of (writers) Thomas Malory and Alfred, Lord Tennyson."

However, just how Welsh he would have been is a "moot point", Dr ap Huw added.

Before the Saxons drove the Brythonic people (Celtic Britons) west and north, there was no recognised entity of an independent Wales, making his nationality hard to ascertain.

The exhibition brings together all the crucial texts which have informed our perception of Arthur for more than a millennium.

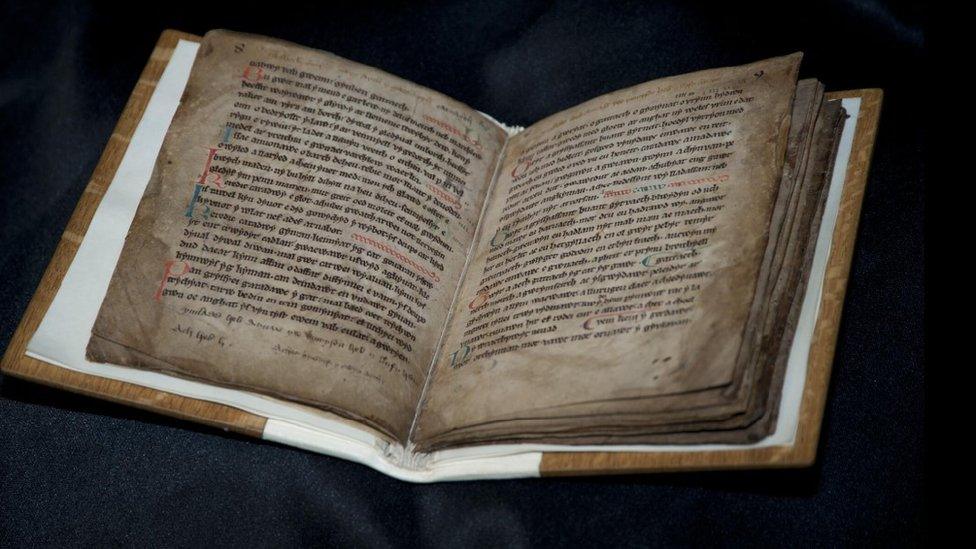

The Book of Aneirin forms part of the exhibition

One of the exhibits is the 13th Century Book of Aneirin, which includes a 6th Century poem describing a battle near what is now Catterick in North Yorkshire.

Dr ap Huw said one reference in it is extremely telling.

A young Brythonic hero called Gwawrddur is described as fighting valiantly against the Saxons "although he was no Arthur".

"It is possible to infer (from this) that the legend of Arthur as a fearsome warlord was already well-established by the 6th Century," Dr ap Huw added.

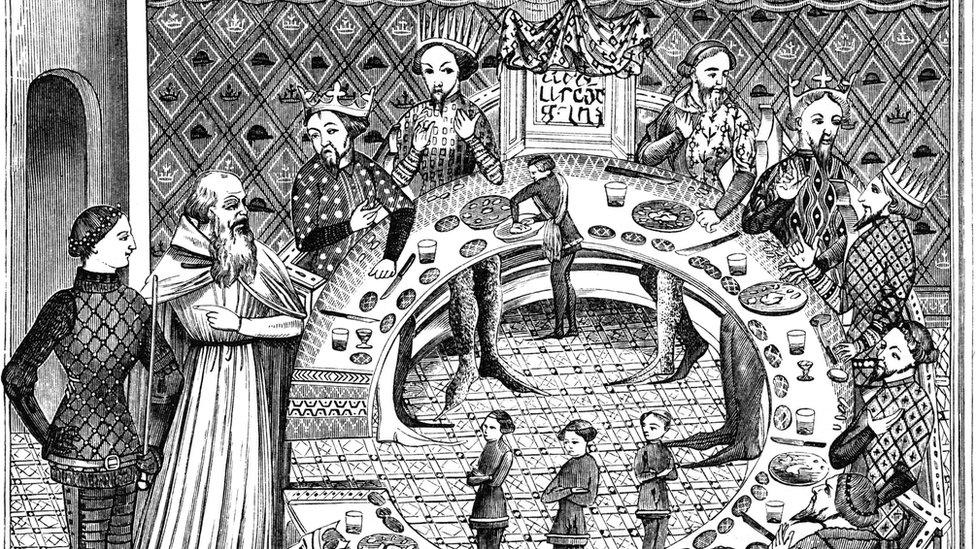

But the man who drew all the threads together and introduced Arthur's wife Guinevere, his sword Excalibur and the Knights of the Round Table was Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Dr ap Huw describes the 12th Century writer as "the most influential author in the history of Wales".

"Forget Dylan Thomas, what Geoffrey wrote had a far more profound impact on world thinking and the perception of Arthur as a Welsh hero," he said.

"Writing in Latin, his ideas rapidly spread throughout Europe, and via Chretien De Troyes, fed into the French-Norman ideals of chivalric kingship.

"Geoffrey claimed as his source an ancient Welsh manuscript which was then lost, never to be found. Read into that what you will, but what is certainly true to say is that it is still essentially Geoffrey's version of King Arthur which we are taught as children, right up to the present day."

Arthur's castle Camelot and other characters such as the wizard Merlin are then referenced in the 13th Century Black Book of Carmarthen.

There he is described as "a war veteran who has lost his wits in battle in Scotland, and has developed the gift of being able to talk to animals".

But it was not until the 15th and 16th Century that "Arthur Mania" reached its heights after William Caxton published Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur.

While Geoffrey of Monmouth set Camelot in the former Roman stronghold of Caerleon, near Newport, Malory anchored it as a thoroughly English tale.

So much so that King Henry VII named his eldest son Arthur in honour of the legend.

By 1534, Polydore Vergil's Anglica Historia had debunked much of Geoffrey of Monmouth's work, and cast doubt on the very existence of a historical Arthur at all.

"Virgil's account wasn't wholly accepted. John Prise - a lawyer for Thomas Cromwell - published a rebuttal in defence of Arthur, but by then the historiographic interest in Arthur was already fatally damaged.

"That's not to say we'd forgotten about him altogether. Edmund Spencer's Faerie Queene drew heavily on Arthurian tradition and, when it was presented to Queen Elizabeth I in 1590, she was so delighted that she awarded him a pension of £50 a year for life," Dr ap Huw said.

"But by then Arthur had become a Britannia or Gloriana-type figurehead for a nation.

"The historical Arthur was dead…though there are some who say he never died, and is simply waiting to wake again when his country needs him."

- Published14 January 2017

- Published18 December 2016