Mental health: Living with Borderline Personality Disorder

- Published

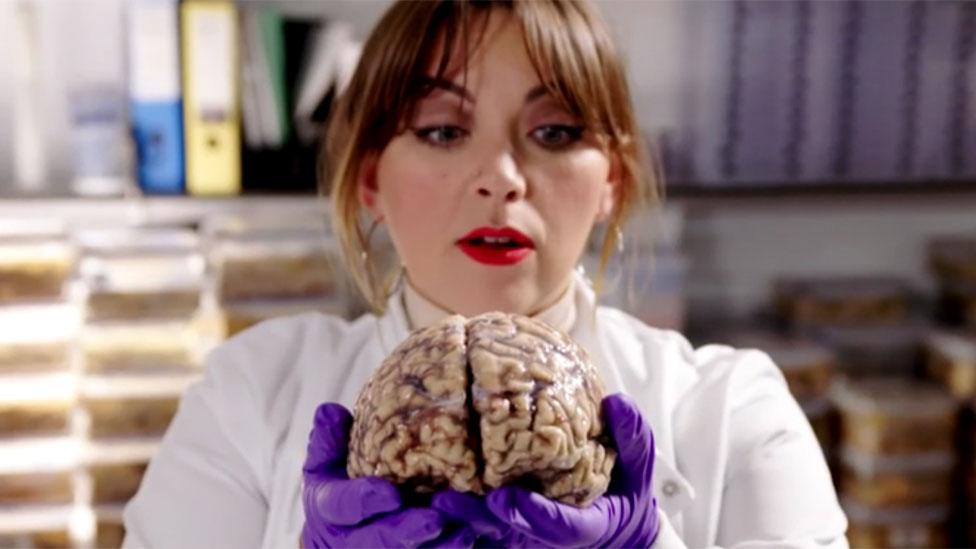

'I was misdiagnosed, isolated and left feeling suicidal'

Two thirds of Welsh people have no one to talk to about their mental health concerns, according to fresh research from Time To Change Wales, a partnership of three mental health charities - Mind Cymru, Hafal and Gofal.

On Time to Talk day, they are encouraging people to open up about their difficulties.

Here, Bethan Rees, 30, from Caerphilly, explains how not being able to talk about her mental health condition left her misdiagnosed, isolated from work and wanting to take her own life.

For most young people, the start of their career is a time of excitement.

But for me, with an undiagnosed mental health condition, it didn't turn out like that.

The moods I had always struggled with came to the surface.

Aged 22, I was working for a press agency in Cheltenham, writing press releases and copy for websites.

It was high-pressured and demanding, with tight deadlines and a large workload.

Yet, despite being qualified for it and excited by it, it became clear I was struggling.

I kept getting behind with tasks and being overwhelmed by the workload.

Colleagues accused me of daydreaming at my desk and being distracted and unable to concentrate.

When bosses tried to give me feedback, I would burst into tears, or get very emotional and angry.

The work place became increasingly unbearable and after 18 months I left.

Bethan and her current boyfriend Karl Powell, 33, who helped her seek help from her GP

I moved back to Cardiff to live with my parents and secured another role in public relations.

But the same thing happened and I began to get behind.

Bosses asked me why I was struggling and I simply couldn't tell them.

But because I knew I might be fired again, I became incredibly anxious.

I felt guilty and panicky, but most of all I felt helpless.

Once more, I would cry at the slightest bit of feedback, or at other times, I became manic - doing 100 things at once.

I went to the doctor, who diagnosed anxiety and depression and put me on anti-depressants.

But they made me sleepy, and my work place was so busy, I couldn't be accommodated and was forced out of that job too.

By this point, my confidence was shattered and what had unfolded in my work life now spiralled into my personal life too.

My parents were confused, not understanding why I couldn't hold down a job.

My long-term partner at the time also ended our relationship because he couldn't cope with my erratic moods.

I felt too ashamed of how I was feeling to talk to people and I thought that if I did, they would see me as weak and incompetent.

I had suicidal thoughts and outbursts where I would throw stuff, dig my nails into my wrists or scream into the pillow to release my anger.

It just felt like I would never be the person I wanted to be and I didn't understand what was wrong.

Ultimately, things came to a head in October 2017.

By then, I had a new boyfriend but one day, for no reason, I just exploded in front of him.

There was no trigger - there rarely is - but I felt so intensely hopeless and miserable I told him I didn't want to live any more.

As I viewed it, I didn't fit in, so what was the point of being around?

Seeing how distraught I was, he made an emergency appointment with a different GP and insisted on coming with me. That doctor told me I should never have been on anti-depressants and that instead I needed mood stabilisers.

A psychiatrist I was referred to then diagnosed Borderline Personality Disorder, otherwise known as emotional instability.

I had never heard of this, but when I looked up the symptoms, I had them all.

They included struggling to maintain stable relationships, having suicidal thoughts and intense emotions that would change rapidly.

Then there was acting impulsively, feeling paranoid and suffering intense outbursts of anger.

Bethan with her medal from the 2017 London Marathon. She took up running to help alleviate her anxiety

Reading the list of symptoms, I felt a wave of relief, because I had always felt there was more to it. But I was also surprised, because it had gone on for so long - how had no one spotted it before?

Since my correct diagnosis, I have been put on mood stabilisers and life is much better.

I've secured a new job in the charity sector and my bosses, aware of my diagnosis, have been incredibly supportive.

Seeing a psychiatrist and counsellor have also helped, as has taking up running, as I find this greatly reduces anxiety.

But importantly, I am now finally able to talk to people. I recently told my best friend everything and she said she was so relieved I'd finally spoken to her - she had known something was wrong but just didn't know how to help.

Because of the importance of this, I've become a champion for Time For Change Wales, a partnership promoting mental health training in workplaces to end stigma and discrimination.

On their Time to Talk day, I would just like to encourage people who know there is something wrong with their mental health but don't necessarily know what, to keep talking until they find someone who can help.

- Published25 January 2018

- Published2 January 2018