Woman recounts career fighting sexism in engineering industry

- Published

2018 is the UK's Year of Engineering, with a key aim being to recruit more women into the field. Here, one former Welsh engineering graduate, Laura*, tells of 20 years of sexism in the industry, and how times are finally changing.

Growing up a teenager in the nineties amid a wave positive discrimination, I didn't think twice about pursuing a career in engineering.

I loved science and maths, so accepted a place at Cardiff University to study architectural engineering.

But despite there being more women than ever on the course, we were still less than 10%.

Our numbers were so few, male students would stop us in the engineering building to ask if we were lost.

I thought this was because people were just not used to seeing female engineers, not because they thought there was something "wrong" with us being there.

But in my first year of industry, my eyes were opened.

The company I worked for was building a new stretch of road with 20 bridges.

I was part of the structures team but when I arrived alone at a bridge for the first time, the subcontractors refused to work with me, demanding a man.

Building had already begun, so I stayed regardless, checking over the measurements and realising the previous male engineer had made some mistakes.

No one believed me, and it was only when my male boss proved I was right, that the contractors changed their view and accepted me.

What became clear, though, was that these men didn't know how to work with a woman.

Some flirted outrageously, inviting me on holiday.

Others treated me like their sister or just avoided me completely.

I couldn't understand what the issue was, but it was a steep learning curve and it didn't end there.

In 2003, following an engineering masters [degree], I was hired by an oilfield services company to lead 16 mechanics on a boat.

Day one, stood before the team, a burly mechanic asked my boss why he had sent them "a girl".

In front of me, he replied: "Well, you know what it's like. We have to make up the statistical requirements."

The mechanic later told me I wouldn't be up to the job and set out to prove this.

He handed me a steel plunger weighing 40kg - about the weight of a collie dog - then asked me to carry it from the bottom to top deck, up three flights of ladders. Luckily, I had just finished rowing for my university so didn't break a sweat, even when I was sent back for another two.

He then asked me to open some nuts on a triplex pump the size of a Land Rover, using a 7kg sledgehammer.

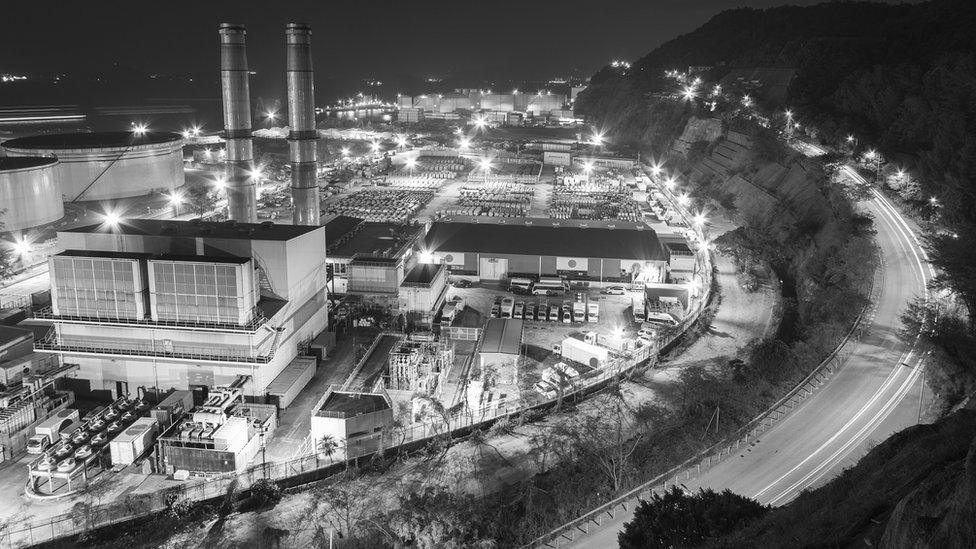

Using sledgehammers and carrying heavy equipment is all part of a engineer's job

I let him believe I would be clueless, then I swung the sledgehammer as hard as I could and knocked the nut off on my second go.

He stood back and said: "Oh, so you know how to use that?"

I replied: "That might have been one of the reasons they gave me the job."

I then got the men to show me how to strip and fix everything on the boat, only allowing them a 15-minute lunch break.

At the end of the day, the burly mechanic tapped me on my back and said: "You can stay."

I did, of course, and they soon seemed to forget I was "a girl".

But the hours were dreadful and the environment dangerous, so, eventually, I left.

I completed a PhD, then took a role in the oil and gas department of a management consultancy.

I thought things in the corporate world would be better, especially as the workforce was nearly 50% female, but I was horrified by the immature attitudes and egos.

I was patronised at meetings, and my qualifications questioned.

At the time of appointment, five of us went for the same rank of job.

Yet the men were given more senior roles despite the women having more experience.

At Cardiff University, 23% of its engineering undergraduates are currently women, compared to the typical figure of 13%

Last year, I discovered I was paid 30% less than the man who held the post before me when he was the same rank.

It took a complaint from me, then a six-month review, for my salary to be upgraded.

The inequalities don't stop with HR, however.

I am often the only woman in meetings. And these meetings will often start with the men shaking hands, then kissing me on both cheeks, often pulling me off balance as I try to extend my own hand.

I feel marked as different before we've even sat down but how can I explain this without sounding neurotic?

Building bridges: Many engineering companies are now much more aware of the need to recruit and retain women

I also haven't worn a skirt since I introduced myself to one of the partners as a petroleum engineer, then saw him look me up and down and almost burst out laughing.

It is not all bad news for women, however.

I recently spent two years on secondment to an oil and gas company and was relieved to find that things had changed dramatically since I was on the rigs.

Although the men still outnumbered the women, the company ran a "diversity network" and taught men and women how to work together, largely based on the teachings of American academic Deborah Tannen.

To me it seemed that, after my arduous journey of acceptance, the world of engineering is finally moving towards gender equality.

It's just disturbing to realise the journey has barely begun for the corporate world.

*Laura's name has been changed to protect her identity

- Published15 February 2018

- Published13 February 2018

- Published20 January 2018

- Published14 January 2018