From farm to fork: The future of Welsh lamb post-Brexit

- Published

Welsh lamb is marked on the shelves

It was the only lamb Queen Victoria would serve in her household because it was the most tender she had tasted.

More than a century after her reign, and Welsh lamb is still a favourite in homes across the world.

But from farm to fork, the industry faces significant challenges as a result of the UK's imminent departure from the European Union.

In the Ceiriog Valley, in Wrexham, Caryl Hughes is the fifth generation of her family to farm the land and its thousands of sheep.

"I'm pretty optimistic," the 27-year-old tells me, as we follow more than 3,000 sheep to the fields.

"There's going to be a lot of challenges, I must admit, over the next few years and we're probably going to see some quite depressing times maybe in the sector. But I think with every challenge there's opportunity.

"I think the sheep sector in the uplands is going to be quite a high risk. To get that product off this land and into that market it's going to need a bit of help otherwise the cost of that product is going to be too much," she adds.

Caryl Hughes is optimistic about the future post-Brexit

Unlike many upland sheep farmers, the family farm doesn't dependent on EU subsidies for most of its income.

Most Welsh farmers currently receive about £250m a year in direct payments from the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Ministers in Westminster have promised to maintain current funding levels until 2022, while the Welsh Government will continue with the EU's Basic Payment Scheme until 2020 before introducing a five-year "transition" towards a new system.

Is Brexit a concern for the lamb industry?

An hour or so away at Welshpool livestock market, business is booming thanks to a drop in the pound following the 2016 referendum.

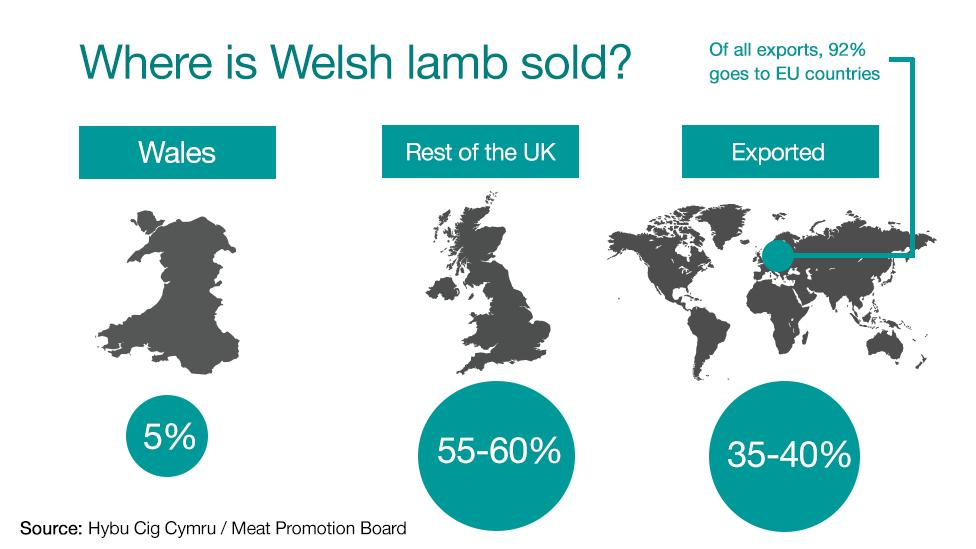

But, with 92% of Welsh lamb exports sold to EU countries, there could be a very painful divorce around the corner, with one farmer saying this could be "a bit of a honeymoon period".

As members of the EU's single market and customs union, Welsh lamb exports to France or Germany face no import or export taxes and no checks at the border. A failure to reach a UK-EU trade deal could see Welsh lamb products face tariffs of more than 40%.

It would be "catastrophic" for sheep farmers, says John Richards, of the Meat Marketing Board, Hybu Cig Cymru (HCC), although he says Theresa May's plan of reaching a tariff-free trade agreement with the EU, outside the single market and customs union, "would be very positive".

The ability to strike independent free trade agreements with countries around the world is one of Downing Street's main reasons for not being in a post-Brexit customs union with Brussels, although there are stark warnings from within Wales about trading with New Zealand.

Most Welsh lamb is sold to the rest of the UK

The industry faces either a "perfect storm" or complete destruction, they warn.

The reply from 11,000 miles away: Keep calm and carry on trading.

"We've actually got no more land in New Zealand in which we can develop," says New Zealand Trade Minister David Parker.

"It's not like we've got an expanding capacity to produce high volumes of either dairy products or sheep products, so I suspect that some of those concerns, while I'm sure keenly felt, aren't quite as bad as people might think."

Exporting lamb is big business for the Kiwis - the country exports 80% of its lamb production every year and it is the biggest exporter of lamb into the UK market.

New Zealand has a tariff-free quota of 228,000 tonnes of lamb it can sell in to the EU and UK markets every year - how to split the quota post-Brexit has already drawn objections from politicians in the country's capital, Wellington.

At the abattoir

On a quiet street in the village of Raglan in Monmouthshire, the potential impact of Brexit is less of a concern for Neil James who runs the local butchers.

Some of the bigger players in Wales have hundreds of workers on their books and rely heavily on hiring people from other EU countries - 63% of abattoir staff and 90% of slaughterhouse vets are EU nationals.

Butcher Neil James at his abattoir in Monmouthshire

How difficult it will be to hire meat processors from Poland or Portugal after Brexit depends on the UK Government's plans for a new immigration system set to be outlined in the coming months.

But as a local butcher who hires, buys and sells, Brexit is not nearly as much of a concern as competition from the supermarkets.

'I don't want the price of lamb to be too dear'

In Abergavenny, a Morrisons has now been built where the historic livestock market stood in the town centre, and signs outside declare the store's commitment to selling 100% Welsh and British red meat products.

The sticker labels read "Protected Geographical Indication" or PGI - the EU's scheme for preventing cheap knock-offs of a particular product.

Hybu Cig Cymru say the designation "is recognised as a mark of quality" and a 2013 review found it equated to £1m extra to the industry in Wales every year.

A replacement system or continued recognition of Welsh products under the EU's scheme post-Brexit is another thing that needs to be discussed.

Shoppers in Morrisons are split - some lamb eaters see the value of buying Welsh, others look only at the price.

It's a label that carries weight on the continent, says the industry, but Helen Davies, of the National Sheep Association (NSA), says: "We really do need to probably market the product here perhaps a bit more aggressively than what we are at the moment."

John Richards adds "there are big opportunities out there for" Welsh lamb.

Japan, China, and the Middle East - there's a long list of potential new markets.

It gives Ms Davies cause for optimism.

"We will survive," she said. "We all might have to work just a little bit harder to survive to start off with but I think once we've got over that initial sort of coming out of Brexit, I think there will be a positive future for us."

It's difficult on the Brexit frontline, but one thing is for sure - the Welsh lamb industry is up for the fight.

Wales Live is on at 22:30 BST on Wednesday on BBC One rWales.

- Published1 February 2017

- Published28 November 2016