Rachel Day died of sepsis 10 days after diagnosis

- Published

Rachel Day was a healthy, happy 29-year-old - then she was struck down by sepsis

Rachel Day's mum Bernie had been trying to get hold of her all morning.

When she finally did, instead of relief all she felt was terror.

Her daughter was screaming uncontrollably and begging for help.

As Bernie rushed to help, not knowing what she would find, 29-year-old Rachel was rapidly succumbing to sepsis as it ravaged her body.

Days later, Rachel was dead.

On World Sepsis Day, Bernie, from Cardiff, tells Rachel's story.

It was during lunch with my husband that I first knew something terrible was wrong.

I had texted Rachel that morning, but she hadn't replied.

Feeling uneasy, I rang her.

But when she answered, it was a noise I will never forget.

She was screaming uncontrollably at me, screaming in pain, screaming for me to get there.

I sped to her flat, keeping her on loudspeaker as I drove.

But when I got there, I was greeted by a terrifying sight.

Rachel was lying in bed, unable to move.

Her mouth was blue and her legs were mottled and swollen, spasming with cramp.

"Don't worry, my darling," I said, desperately trying to reassure her as she screamed in pain. "We'll get you help. You'll be okay."

But in reality, I was already too late. She was in septic shock and she was dying.

I just didn't know it yet.

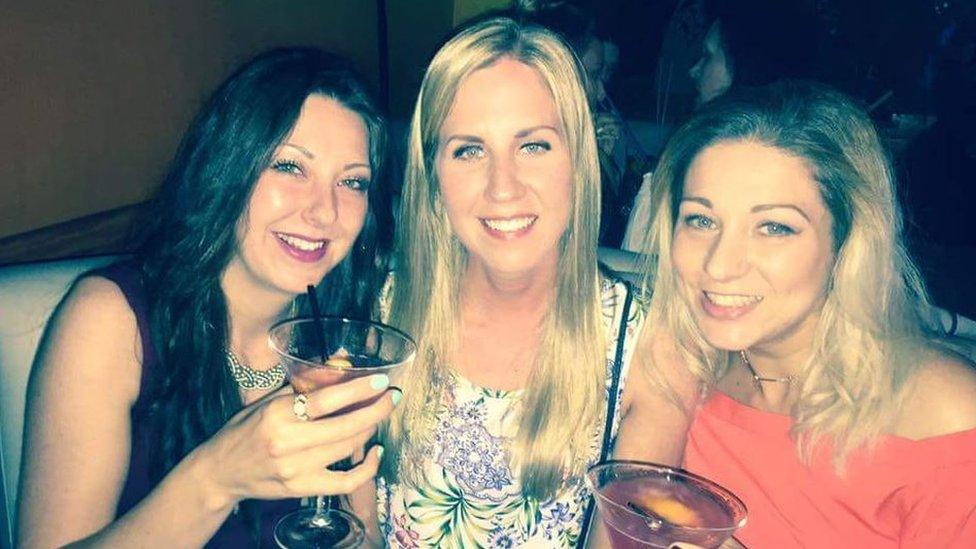

Rachel enjoyed working at a leisure centre and had dreams of opening a dog creche

It was a situation made all the more impossible by the fact my daughter had been so healthy.

Rachel loved sport and fitness, and for a long time had worked as lifeguard and swimming teacher at Llanishen Leisure Centre, before becoming assistant manager.

There, she mentored younger staff and made friends with her sunny personality and strong work ethic.

She was beautiful, in the bloom of her life, excited about a business idea to change her career path and open a creche for dogs.

But that weekend - the second May bank holiday in 2017 - she fell ill.

It came on so quickly.

Just the day before, we had been out together, enjoying a boat trip around Cardiff Bay then going on to drink cocktails.

She lived with a close friend and I know that on the Sunday, she had gone to bed earlier than usual, complaining she felt unwell.

At 4am on the Monday morning, she had knocked on her flatmates' door, asking her to take her to A&E.

She was vomiting and complained of feeling breathless.

She told her flatmate she was frightened she was going to die - a common symptom of sepsis as it takes over the body so quickly.

Her flatmate did all she could - driving her straight to A&E at Cardiff's University Hospital of Wales.

Sepsis: What is it - and how to spot it?

She was told there was a five-and-a-half hour wait to see a doctor, and that she might be best going home and taking Paracetamol.

Rachel followed the advice and went home to bed.

But at 7am, her flatmate left for work, reluctantly leaving her alone with just a sick bucket and a glass of water.

Like me, she texted throughout the morning to check Rachel was okay.

Like me, she didn't receive a reply.

It was only when I phoned, and Rachel managed through her pain to tap the screen to answer that we knew the horror that had engulfed her.

Rachel with her father, Steve Day, at a family wedding

New guidelines for managing sepsis say it needs to be treated with intravenous antibiotics within the hour.

But we were already way behind.

It had consumed her, constricting her movements as it began ravaging her internal organs and tissue, leaving her in extraordinary pain.

The following sequence will be etched forever on my mind.

At first, despite the urgency of my 999 call, just one paramedic came to her flat.

He sent for an ambulance and two more paramedics arrived.

Rachel was still screaming in pain, and they couldn't even find her blood pressure, it was so low.

It was one hour and 20 minutes before she reached A&E - despite it being just a few miles away.

As we drove there, I was screaming inside my head for them to hurry.

Rachel and her mother Bernie

It was only as we neared hospital that the word sepsis was first mentioned. Sepsis, I thought. What was sepsis?

But it was clear that the doctors and nurses on the Intensive Care Unit knew.

As soon as Rachel arrived, she was attached up to one drip and another, pumped full of antibiotics and fluids.

A consultant told Rachel she was going to be put under sedation to give her body a rest.

She reassured her she wouldn't die but, in reality, doctors probably knew she would be lucky if she lasted 24 hours.

In fact, Rachel lasted 10 days in intensive care.

She fought and fought.

But it was now 12 hours after she had first attended A&E with symptoms and the sepsis was in full control.

She had blood clots on her lungs, brain and kidneys. Her body was swollen, her beautiful face and nose disintegrating and turning black.

After six days in an induced coma, she was slowly brought back round by doctors, so they could assess what damage had been done to her brain.

Rachel couldn't talk but she could communicate through blinking - one for yes, two for no.

She recognised the voices of close friends, blinking when they sang her funny Dr Dre songs.

Rachel with her friend and flatmate Sohaila Ali, who initially took her to hospital

I would sing to her in my terrible voice, mainly lyrics from the Carpenters' hit Close to You, which I had sung to her since she was a baby.

Needless to say, she blinked twice. Shut up, mum, she was saying. Stop singing.

She still had her sense of humour and we thought that night that she might just make it.

And on the following Sunday - day seven - we held out even more hope when she opened her eyes for her dad.

But her body was too tired to do it more than once, and she was put back under sedation.

It was the next day, on Monday, 5 June, that consultants broke the news to us that in order to save her life, they would need to amputate her limbs.

They wanted to take both legs under the knee and her left arm.

Although horrific, it was our view that she would be able to cope with this.

Before surgery, the doctors let me slide onto her bed and give her a cwtch [hug].

But when the surgeon came to talk to us afterwards, he told us the damage to her tissues had been so severe, they had had to amputate both of her arms, leaving her a quadruple amputee.

To say we were distraught is not touching it. How would Rachel cope like that? What sort of life would she have?

It was at this point I went to the chapel in the hospital.

I was screaming at God, asking why this had happened to Rachel and not me.

I walked to the window, shaking violently and wanting to throw myself out.

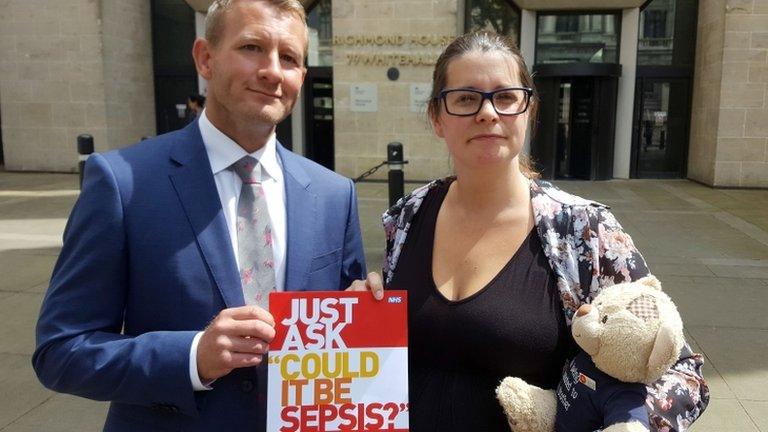

Bernie Day with photos of her daughter. She is now campaigning to raise awareness of sepsis

But the chaplain must have heard me. She rushed in, wrapped a blanket around my shoulders and calmed me down.

She told me I was a mum, and as a mum, I knew what I had to do.

But then there came the final blow, delivered by a consultant in tears.

Rachel had multiple-organ failure. She wasn't going to make it anyway.

We invited all her friends to the hospital, let people say goodbye, put candles around her room, then switched off her life-support machine.

This was Wednesday, 7 June 2017, and my beautiful girl was gone in minutes.

Rachel with some of her closest friends

That was 16 months ago. More than 400 people came to her funeral.

Obviously, we have questions about Rachel's death. Could an earlier diagnosis have saved her?

But for now, our family is focusing on campaigning to make people more aware of sepsis.

The illness kills upwards of 44,000 people in the UK - more than bowel, breast and prostate cancer combined.

The money we have raised has gone towards implementing a 'Sepsis 6 Pathway' at the University Hospital of Wales.

This means anyone admitted with a fever or signs of infection will be checked against red-flag symptoms of sepsis.

We are now hoping to train paramedics and GPs to spot early warning signs, as well as getting the pathway into more hospitals.

Of course, we are also focusing on getting Rachel's story out there to the wider public.

I don't want to let her down.

If she died to save others, then I have to do what I can to get the message out there.

What is sepsis?

Sepsis is triggered by infections, but is actually a problem with our own immune system going into overdrive.

It starts with an infection that can come from anywhere - even a contaminated cut or insect bite.

Normally, your immune system kicks in to fight the infection and stop it spreading.

But if the infection manages to spread quickly round the body, then the immune system will launch a massive immune response to fight it.

This can also be a problem as the immune response can have catastrophic effects on the body, leading to septic shock, organ failure and even death.

Symptoms include:

slurred speech

extreme shivering or muscle pain

passing no urine in a day

severe breathlessness

"I feel like I might die"

skin mottled or discoloured

Symptoms in young children, external include:

looking mottled, bluish or pale

very lethargic or difficult to wake

abnormally cold to the touch

breathing very fast

a rash that does not fade when pressed

a seizure or convulsion

Source: NHS Choices, external

- Published28 November 2016

- Published26 January 2016

- Published27 July 2016

- Published10 March 2017

- Published22 January 2015

- Published1 September 2016